A firefight between six US marshals and two boys and their dog began a movement founded on anti-government ideology. The internet age has spread its message wider. The following was originally published in 2017. I have chosen to provide three minor updates, which do not change the direction nor meaning of the author’s original intent. In addition, I have added an interview to this column, which I had conducted with Sara Weaver in July of 2003. ~ Ed.

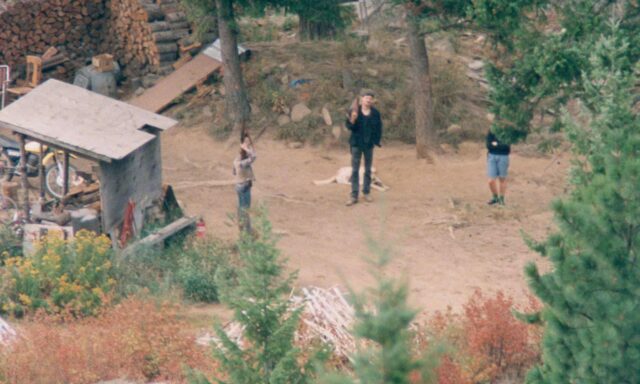

A surveillance photo of the Weavers with guns on the property in Ruby Ridge, 1992. Photograph: PBS

Twenty-eight years ago today, in a remote corner of northern Idaho, the modern militia movement was born in a firefight. On the streets of Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017, observers could see from the presence of well-armed men in fatigues that that movement was still with us. But back in 1992, they hadn’t yet formed. A firefight between six US marshals and two boys and a dog, changed all that.

On 21 August that year, the marshals went to a location that became known as Ruby Ridge, near Naples, to scout a location where they might ambush a fugitive, Randy Weaver. Weaver had been holed up for a year and half with his family in his cabin, having failed to attend his trial on firearms charges.

The marshals aroused the attention of Weaver’s dogs. Alarmed, they retreated to a small clearing to the west of the house. Weaver ventured out, looking for the source of the disturbance. His 14-year-old son, Sammy, and his young friend Kevin Harris did the same on a separate route, following on the heels of a dog, Striker.

Weaver met the marshals first, they challenged him, and then he retreated into the brush. A minute later, the two boys and the dog came out of the woods. There was an exchange of fire. The exact order of events has been disputed for over a quarter of a century, but the end result was that Sammy Weaver, deputy marshal Bill Degan and Striker were all dead.

The Weavers retreated to their cabin and laid Sammy’s body in a shed. Over the next day, federal and local officers – now under the command of the FBI – began to arrive in their hundreds to join the siege.

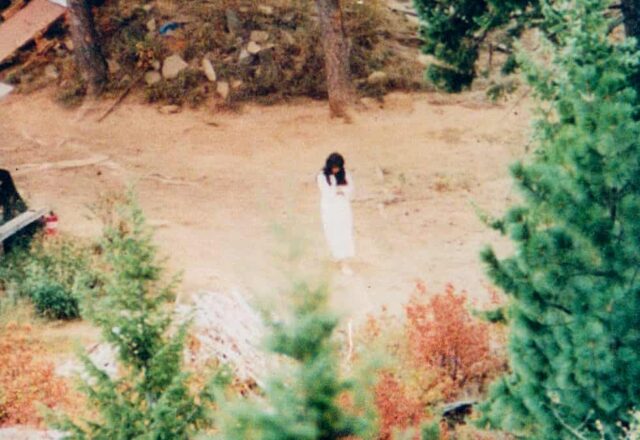

The next day, 22 August, operating under rules of engagement that allowed deadly force, an FBI sniper wounded Randy Weaver as he checked on Sammy’s corpse. The same sniper then shot Randy’s wife, Vicki, dead and wounded Kevin Harris.

The last photograph of Vicki Weaver before she was killed by an FBI sniper.

The siege dragged on to the end of August, and the scene became a circus.

Neo-Nazis from the nearby Aryan Nations compound at Hayden Lake showed up to protest.

Other far-right groups poured in from all over the country to stand against what they saw as the persecution of an innocent family by a tyrannical federal government.

Ruby Ridge was resolved, in the end, not by agents, but by civilian negotiators including Bo Gritz, a former green beret, prolific conspiracy theorist, and the Populist party’s presidential candidate, who was briefly on a ticket with the ex-Klansman David Duke.

Along with the botched Waco siege the next year, during which 76 besieged members of the religious group the Branch Davidians died, Ruby Ridge badly damaged the credibility of the Clinton-era FBI (Bill Clinton became US president on 20 January, 1993), and boosted some emerging narratives on the far right: that the feds were coming for the guns and property of those, like Weaver, who wanted no further contact with a country they saw as irredeemably corrupt.

Along with the botched Waco siege the next year, during which 76 besieged members of the religious group the Branch Davidians died, Ruby Ridge badly damaged the credibility of the Clinton-era FBI (Bill Clinton became US president on 20 January, 1993), and boosted some emerging narratives on the far right: that the feds were coming for the guns and property of those, like Weaver, who wanted no further contact with a country they saw as irredeemably corrupt.

Mike German, a former FBI officer who at the time of Ruby Ridge was working undercover in white supremacist groups, and now Fellow at NYU’s Brennan School for Law and Justice, says that while the FBI “inherited a mess” when it took on the badly handled case, the bureau “ultimately saw it as a mistake, and an escalation that had caused significant harm, including to children”.

They made it worse, he says, by “engaging in a cover-up to hide their mistakes”. In 1997, E Michael Kahoe, who had helped supervise the FBI’s response, was sentenced to 18 months in a federal prison for burying documents critical of the agency’s approach to the siege ahead of the prosecution of Weaver and Harris.

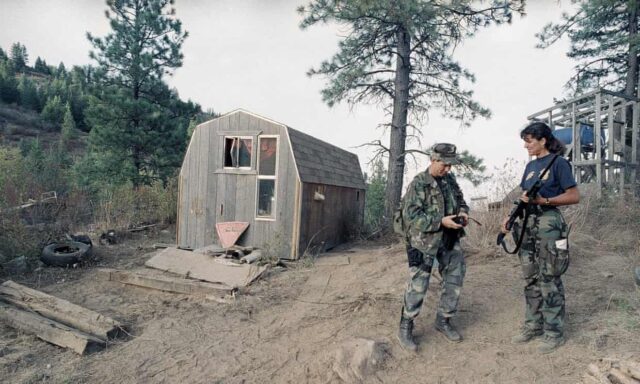

Randy Weaver supporters at Ruby Ridge in northern Idaho. Photograph: Jeff T Green/AP

Bill Morlin reported on Ruby Ridge for the Spokane Spokesman-Review, and is now a fellow at the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). He has monitored the far right since the early 1980s. He says simply: “Ruby Ridge became a demarcation point for the rise of the modern militia movement.

“It put the fertilizer in their minds which sprouted radical anti-government beliefs.”

For a radical fringe, with especially intense anti-government beliefs, it became a reason to form paramilitary groups and stockpile arms in the expectation that they would have to defend themselves against totalitarian overreach from a “New World Order”. Some expected the agents of this conspiracy to swoop in in black helicopters and establish world government, while persecuting patriots.

David Neiwert, a contributing writer for the SPLC and author of several books on the far right says the Ruby Ridge myth was potent. Neiwert says it allowed groups to say: “You’re next! They’re going to round people up and put them in concentration camps.” He says some groups even had detailed maps claiming to show where the network of camps would be located.

Groups from Montana to south-west Oregon combined different forms of anti-government ideology, such as fears about gun confiscation and grievances about federal land management practices.

Morlin says that the ideology of “local supremacy” was also central to movement beliefs. “They said the only real authority in law enforcement is the local sheriff. The feds have no jurisdiction. Some people still believe that.” To this day, pro-milita sheriffs, such as Glenn Palmer in Oregon, hold political power in the region.

From this, and a welter of spurious legal beliefs, many groups mounted direct challenges to the authority of federal agencies such as the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. Many agents of these bodies faced violence or harassment in the course of their work during the 1990s.

Morlin says that militia groups, large and small, used the story of Ruby Ridge to recruit people, and to amplify existing anti-government beliefs: “The whole idea was to play on people’s fears.”

The rise of the movement was fortuitously timed with a broader uptake of internet technologies. Morlin says that militia groups made intense use of these technologies to spread their messages and work around mainstream outlets.

Editor’s NOTE: In July of 2003, I was privileged to interview Sara Weaver, daughter of Randy and Vicki Weaver. My first airing of said interview was just weeks later – on the 11th anniversary of said tragedy. The sound quality is not what I would prefer at certain spots, but the interview with Sara is something else. ~ Jeffrey Bennett, Editor

After the anti-government zealot Timothy McVeigh bombed a federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995, killing 168, including many children, the movement came under more scrutiny. While many believe the movement dropped off sharply after McVeigh’s act, German thinks that its real numbers are difficult to assess, and that many simply turned their attention to other activities, such as acting as vigilante immigration enforcers on the southern border.

In the years between their prominence in the 1990s and their resurgent public visibility today, the militias’ basic ideology – stressing federal overreach, local supremacy, and a hardline constitutionalism – gained a greater acceptance among many in rural areas.

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents stand next to the outbuilding located near the Randy Weaver home near Naples, Idaho. Photograph: Gary Stewart/AP

Contemporary “patriot movement” groups such as the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters, or the various “Light Foot Militias” seen on the streets of Charlottesville, do not generally foreground fervidly conspiratorial anti-government rhetoric. For the most part, they fastidiously disavow racism and white supremacy.

Unlike those in the earlier wave of the militia movement, whose adherents mainly confined themselves to rural and provincial areas, newer groups have come, bearing arms, into the heart of liberal cities. This has been apparent during the wave of rightwing protests that have swept cities from Berkeley to Boston since Donald Trump’s inauguration. Usually, militias turn up on the basis of providing security and protection for “free speech”.

In the Trump era, these groups are far more emboldened, and often organize openly on social media. They’re also able to bring weapons into public places in a way that was not previously possible. Changing gun laws – such as proliferating open carry provisions, the end of the assault weapons ban, and the supreme court’s Heller decision – mean that groups can bring semiautomatic weapons, sidearms, and body armor into cities unchallenged.

NOTE: This author had no clue! ~ Ed.

And if their rhetoric seems less far out, it may be because some of the ideas they nurture have been brought into the mainstream by broadcasters such as Alex Jones, who has embraced the 9/11 “truth” movement and united it with well-established themes within the militia movement.

Their willingness to turn out in numbers in volatile situations is a new and striking development. In Charlottesville, Virginia’s governor, Terry McAuliffe, said police had held back because they felt outgunned by militia.

Of the new movements, Neiwert says: “They’re far more dangerous than they were in the 1990s … This has become a huge problem and I don’t see any way out of it.”

In 2020, the shots fired 25 years ago at Ruby Ridge are still echoing in the streets of American cities.

Written by Jason Wilson for The Guardian ~ August 21st, 2020

I will always remember Ruby Ridge.