For nearly five centuries, Res Publica Romana — the Roman Republic—bestowed upon the world a previously unseen degree of respect for individual rights and the rule of law. When the republic expired, the world would not see those wondrous achievements again on a comparable scale for a thousand years.

For nearly five centuries, Res Publica Romana — the Roman Republic—bestowed upon the world a previously unseen degree of respect for individual rights and the rule of law. When the republic expired, the world would not see those wondrous achievements again on a comparable scale for a thousand years.

In print and from the podium, I have addressed the calamitous economic policies that ate away the vitals of Roman society. I’ve emphasized that no people who lost their character kept their liberties. But what about the republic as a form of governance — the structure of representation, the Senate and popularly elected assemblies, laws for the limitation of power and protection of property, and the Roman Constitution itself? Did those ancient institutions abruptly disappear or were they eroded through “salami tactics,” one slice at a time?

It behooves us to know the reasons the republic died. Philosopher George Santayana’s general dictum famously tells us why we should know them: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But there is a more specific and immediate urgency to learning the facts of Roman misfortune: In eerie and haunting ways, Americans at this very moment are living through a repetition of Rome’s republican decay.

No single person, domestic law or foreign intervention ended the Republic in a single stroke. Indeed, the Romans never formally abolished the republic. Historians differ as to when the actual practice of republicanism ended. Was it when the Senate declared Julius Caesar dictator for life in 44 B.C.? Was it in 27 B.C., when Octavian assumed the audacious title of “Caesar Augustus”? In any event, the Senate lived on until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in A.D. 476, though after Augustus it never amounted to much more than an imperial rubber stamp.

Boiling the Frog

The Roman Republic died a death of a thousand cuts. Or, to borrow from another, well-known parable: The heat below the pot in which the proverbial frog was boiled started out as a mere flicker of a flame, then rose gradually until it was too late for the frog to escape. Indeed, for a brief time, he enjoyed a nice warm bath.

Like the American Republic, the Roman one was born in violent revolt against monarchy. “That’s enough of arbitrary and capricious one-man rule!” Romans seemed to declare in unison in 509 B.C. Rejecting kings is a supremely rare thing in human history. The Romans dispersed political power by authorizing two coequal consuls, limited to one-year terms and each with a veto over the acts of the other. They created a Senate in which former magistrates and members of patrician families with long civil or military service would sit. They set up popularly elected assemblies that gained increasing authority and influence over the centuries.

Due process and habeas corpus saw their first widespread practice in the Roman Republic. Freedoms of speech, assembly, and commerce were pillars of the system. All of this was embodied in the Roman Constitution, which—like that of the British in our day—was unwritten but deeply rooted in custom, precedent, and consensus for half a millennium.

Roman freedom and republican governance, to be sure, were undercut by limitations on the franchise and on the always detestable institution of slavery. The Roman Republic was certainly not perfect, but still it represented a remarkable advance for humanity, as could be said of the Magna Carta or the Declaration of Independence.

Cicero

Writers from the first centuries B.C. and A.D. offered useful insights to the decline. Polybius predicted that politicians would pander to the masses, leading to the mob rule of an unrestrained democracy. The constitution, he surmised, could not survive when that happened. Sallust bemoaned the erosion of morals and character and the rise of personal power lust. Livy, Plutarch, and Cato expressed similar sentiments. To the moment of his assassination, Cicero defended the Republic against the assaults of the early dictators because he knew they would transform Rome into a tyrannical despotism.

Ultimately, the collapse of the political order of republican Rome has its origins in three developments that took root in the second century B.C., then blossomed by the end of the first. One was foreign adventure. The second was the welfare state. The third was a sacrifice of constitutional norms and the rule of law to the demands of the other two.

Foreign Adventure

In his excellent 2008 book, Empires of Trust, historian Thomas F. Madden argues that much of the expansionism of the Roman Republic was defensive in nature—that is, the Romans gradually accumulated an empire without any real design to have one. But there is no doubt that after the wars with Carthage (ending in the middle of the second century B.C), the burdens of policing vast territory from one end of the Mediterranean to the other were costly.

Wars also gave excuses to political leaders to spy and conspire, to suspend constitutional provisions in the name of national emergencies. As power concentrated in the hands of military figures, men in service increasingly placed loyalty to their generals ahead of loyalty to the general welfare. Taxes were raised even as the booty (and slaves) from overseas conquests poured in. If Rome had stayed home, its military-industrial complex might have been better tamed.

As both the power and the purse of the central government grew, a long series of civil conflicts arose. Factions fought against each other to gain control over the state machinery. Officeholders chipped away at the restraints on power. More and more, they ignored or secured exemptions from term limits. They issued decrees, tantamount to today’s “executive orders” from the president or new regulations from the bureaucracy, without consideration by representative assemblies. War, as Randolph Bourne would note centuries later, is indeed “the health of the State.”

Foreign conflicts produced another ill effect at home. Many peasants saw their lands ravaged while they were off at war for long periods. And if they still possessed them upon return, they found they had to compete with the cheap labor of the slaves captured in war and put to work by wealthy landowners with political connections.

If Romans by the first century B.C. still cared about the institution of limited, representative government, increasing numbers of them could simply be bribed into compliance using subsidies.

The Welfare State

To fix the economic injustices that war and other interventions created, reformers in the second century B.C. proposed redistribution of land by law. The Gracchus brothers rose to power on just such promises, and though their efforts ended in their assassinations, the principle of robbing Peter to pay Paul caught hold. In 59 B.C., a man named Clodius ran for the important office of tribune on a platform of free wheat for the masses, and won. He was among the first in a long line of demagogues bearing gifts from the public treasury.

At this point, “Kershner’s First Law” (named for the late economist Howard E. Kershner) kicked in: “When a self-governing people confer upon their government the power to take from some and give to others, the process will not stop until the last bone of the last taxpayer is picked bare.” Eventually the central government bailed out profligate cities and provinces, spent huge sums to keep the people entertained, and even issued zero-interest credit to thousands of private businesses in a misguided effort to “stimulate” a sputtering economy.

Historian H. J. Haskell describes how quickly the largesse corrupted republican values: “Less than a century after the Republic had faded into the autocracy of the Empire, the people had lost all taste for democratic (read: ‘representative’) institutions. On the death of an emperor, the Senate debated the question of restoring the Republic. But the commons preferred the rule of an extravagant despot who would continue the dole and furnish them free shows. The mob outside clamored for ‘one ruler’ of the world.”

Warfare plus welfare equals massive revenue needs. Taxes went up but with an interesting twist: The Roman government turned to the private sector to perform much of its tax collecting, legalizing almost any tactic to get the money and giving a large cut to those who got it. The ruthlessness of government was combined with the efficiency of the private sector to produce a crushing and inescapable burden. Even so, by the middle of the first century A.D., deficits and debt led the government to commence a systematic, long-term depreciation of its currency. The silver and gold content of Roman coins eventually evaporated.

Long after the republic expired and the empire was entering its twilight, public welfare was enshrined as a right, not a mere privilege or temporary assist. People were even frozen by law in their professions so that no one could escape the government’s taxes or wage and price controls by changing occupations.

Constitutional Erosion

For several hundred years, the unwritten Roman Constitution boasted features we would recognize today: checks and balances, the separation of powers, guarantee of due process, vetoes, term limits, filibusters, habeus corpus, quorum requirements, impeachments, regular elections. They were buttressed by the traits of strong character (virtus) that were widely taught in Roman homes: gravitas (dignity), continentia (self-discipline), industria (diligence), benevolentia (goodwill), pietas (loyalty and a sense of duty), and simplicitas (candor). Romans knew well that the rules of their constitution were there for good reason and until they were bribed with public money to cast them aside, they frowned on anyone who sought to violate them.

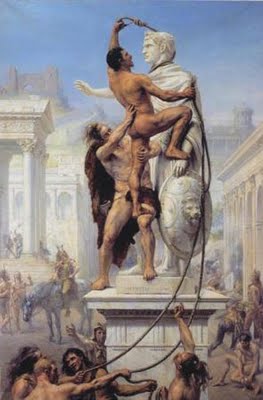

Lesser offices such as magistrate, praetor, censor, aedile, quaestor, and tribune were eventually abandoned in favor of the very one-man rule the republic was founded to replace. Popular assemblies became irrelevant. The Senate evolved into a worthless advisory body of corrupt cronies who cared more for their privileges than for their purpose. By the time the Romans lost it all to foreign barbarians in A.D. 476, the constitution that had once enshrined their liberties was a distant dead letter.

Does any of this story ring familiar? You’d have to be asleep if it doesn’t.

Our own Constitution, barely two centuries old, is in shambles. When Iraq was writing a new one a few years ago, the late night comedian Jay Leno quipped, “Why don’t we just give them ours? We’re not using it.” It was a remark more tragic than funny.

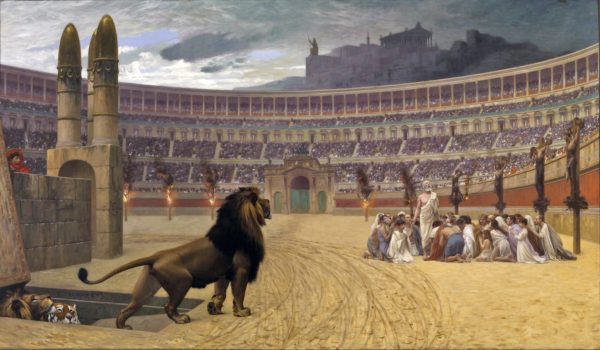

The Christian Martyrs Last Prayer

The “commerce clause” of our Constitution has been twisted and bent until it now justifies almost any intervention from the central government. A Supreme Court chief justice performed the most amazing intellectual gymnastics to sanctify a health care monstrosity as constitutional. Our President rewrites the law as he pleases. He makes “recess appointments” when the Senate is not in recess. He issues executive orders by the hundreds. He presides over agencies that spy on millions of Americans and target political enemies for retribution. But I don’t mean to single out Barack Obama. He’s simply extending a legacy that goes back many years now.

What raises the ire of Americans enough to bring them out into the streets is not an arbitrary breach of constitutional norms but simply the hint that some benefit might be cut back. Tells you something about our priorities these days, doesn’t it?

The catalog of constitutional erosion is fat and getting fatter. My limited intention here is to shake a few people awake and get them to start thinking. I urge the reader to take another look at the Constitution and compile a list of instances of our leaders’ careless and shameless abdication of its prescriptions. Decide for yourself if history is truly repeating itself.

We know the path the Romans took, so we have no excuse for not learning from their experience. Do we really want to keep heading in the same direction?

Not me.

Written by Lawrence W. Reed for Foundation for Economic Freedom ~ January 8, 2014