Why are politics so consumed with the past?

In the fall of 2017, the journalist and poet Clint Smith began to visit sites that held some poignant meaning in the history of American slavery: the human shipment point of Gorée Island, in Senegal; the Whitney Plantation, in Louisiana, where an 1811 slave rebellion is commemorated; Galveston Island, in Texas, the site of the original Juneteenth liberation; and Monticello. Smith’s travels, which he recounts in a new book, “How the Word Is Passed,” began just a few months after the white-nationalist uprising at Charlottesville: the conservative defense of the Confederate monuments was a live political issue, and the reckoning with the racial past seemed to him both under way and partial. “It seems that the more purposefully some places have attempted to tell the truth about their proximity to slavery and its aftermath, the more staunchly other places have refused,” Smith writes. Continue reading

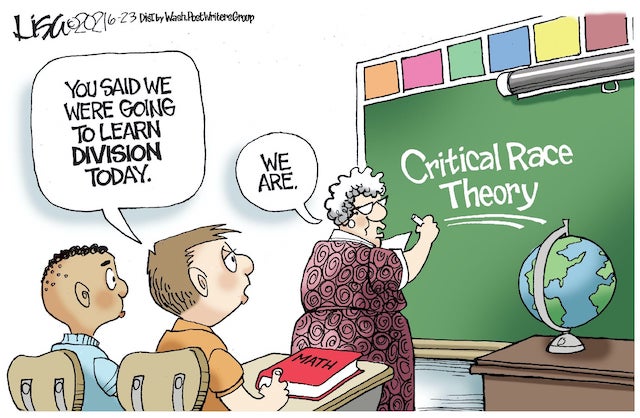

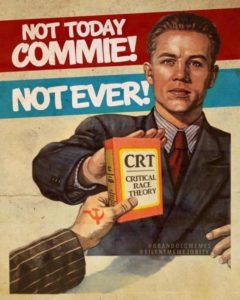

The recent June 21st issue of The New American magazine is a special report on education in America. The people that publish The New American realize that the major problem we have with education in this country is the public school system. An informative article by Alex Newman in this issue is entitled Government Schools vs. Christianity. Among other things Alex Newman noted: Despite the myth of religious ‘neutrality’ and ‘secular’ schooling perpetrated by the government school establishment and its apologists, all education is fundamentally religious in nature. That is just as true in government schools across the United States as it is in Islamic madrassas of Pakistan. The only question is what what religion and what worldview is being taught.” This is a cogent truth that most people, Christians included, never seem to grasp.

The recent June 21st issue of The New American magazine is a special report on education in America. The people that publish The New American realize that the major problem we have with education in this country is the public school system. An informative article by Alex Newman in this issue is entitled Government Schools vs. Christianity. Among other things Alex Newman noted: Despite the myth of religious ‘neutrality’ and ‘secular’ schooling perpetrated by the government school establishment and its apologists, all education is fundamentally religious in nature. That is just as true in government schools across the United States as it is in Islamic madrassas of Pakistan. The only question is what what religion and what worldview is being taught.” This is a cogent truth that most people, Christians included, never seem to grasp.