A remnant from the late ‘20s, “Metropolis” has come into the light once again and in a more complete way. While the industrial environment and modern work have changed, the concern for social justice and questions about technology are just as intense as they were when the film premiered.

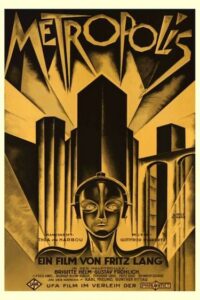

In a search for movies considered classics, I came across the 1927 film, Metropolis. Not knowing what to expect, I was nevertheless interested to know why it was a famous classic of silent film. In watching it, I soon realized why. The film is a work of outstanding artistry. It projects a future reality given the date of 2028. Not at all like modern movies, it is simply a piece of stunning artwork and theater made on film. The skillful and amazing visuals are difficult to describe and have to be seen. They present the mechanical detail of futuristic industrial scenes and activity with intricate beauty that feels astounding. The imaginative cityscape is also a beautiful piece of artwork. The story is accompanied by wonderful background music which is a treat in itself. I think others have written of these aspects more fully than I can here. What I would like to address in particular is its religious aspect.

In a search for movies considered classics, I came across the 1927 film, Metropolis. Not knowing what to expect, I was nevertheless interested to know why it was a famous classic of silent film. In watching it, I soon realized why. The film is a work of outstanding artistry. It projects a future reality given the date of 2028. Not at all like modern movies, it is simply a piece of stunning artwork and theater made on film. The skillful and amazing visuals are difficult to describe and have to be seen. They present the mechanical detail of futuristic industrial scenes and activity with intricate beauty that feels astounding. The imaginative cityscape is also a beautiful piece of artwork. The story is accompanied by wonderful background music which is a treat in itself. I think others have written of these aspects more fully than I can here. What I would like to address in particular is its religious aspect.

The basic drama of the movie is the deep divide between laborers deadened by mind-numbing tasks, and a comfortable well-off class of owners/managers and their clerks who are shown diligently working out the mathematic and scientific calculations needed for a massive enterprise. This class seems to indulge in a high  life of pleasure. Early in the movie, at a fancy party scene in what was described as “the eternal garden,” there suddenly appears in a doorway a woman surrounded by poor children over whom she spreads her arms. She announces to the revelers: “These are your brothers, your sisters.” All stop and stare at this apparition. The son of the industrial entrepreneur and ruler of the city is also staring and is heart-struck by the woman. Her name is Maria and she is identified as a virgin.

life of pleasure. Early in the movie, at a fancy party scene in what was described as “the eternal garden,” there suddenly appears in a doorway a woman surrounded by poor children over whom she spreads her arms. She announces to the revelers: “These are your brothers, your sisters.” All stop and stare at this apparition. The son of the industrial entrepreneur and ruler of the city is also staring and is heart-struck by the woman. Her name is Maria and she is identified as a virgin.

Later a scene reveals that factory workers at the end of the day descend into the “2000 year old catacombs” where there is a crypt surrounded by 8 or 10 crosses. Maria is telling them the story of the Tower of Babel. She says that some people used their minds to imagine and design the tower, but they needed slave-like laborers to build it. Although they spoke the same language, the people could not understand each other. So eventually the town and its tower collapsed. The story as she tells it appears to be a warning to the modern industrial population. She tells the workers that “head and hand need a mediator.” The workers ask, “When will the mediator come, Maria?” She responds, “Wait for him, he will surely come.” When the son appears in the catacombs, Maria says to him, “Oh, have you finally come?” He replies, “You called me. Here I am.” The scriptural intonation of these lines is unmistakable.

In the middle of the film, there is a scene in a cathedral where a monk is heard reading from the Book of Revelation about the end times and the whore of Babylon. The son is listening to this and then sees in the cathedral a statue of the devil accompanied by statues representing the seven deadly sins. Later, the son has a nightmarish vision of a large machine appearing like the pagan god Moloch, opening a huge mouth into which the workers are being thrown. One recalls that Moloch was the god to whom children were sacrificed in ancient times.

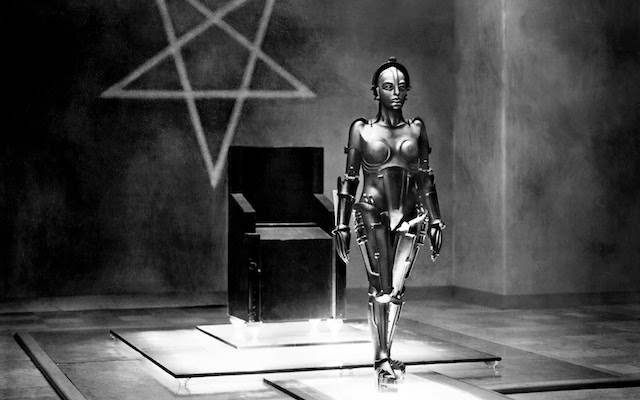

In the meantime, the father and ruler, who has observed the workers in the catacombs listening to Maria, fears they are plotting against him and enlists the help of an inventor, telling him to give the image of the girl to his Machine Man so that a robotic Maria will destroy the belief of the workers in Maria’s holiness. The inventor takes on the character of an evil magician and constructs the robotic imitation of Maria. (There is an occult symbol, the pentagram, hanging in his workplace.) Then the film shows the devil going forth wielding a scythe, and he seems to have entered the robotic imitation Maria. This false Maria then appears as an exotic dancer that enthralls the upper-class men at a revelry, and gradually becomes more and more vividly the image of the whore of Babylon. With an evil gleam in her eyes, she then goes to the laborers to incite them to rebel against the factory owner and arouses them to destroy the machines upon which the city depends. In this part of the movie, one wonders if this is a depiction of a Marxist war of the classes. But it takes a different turn.

In the meantime, the father and ruler, who has observed the workers in the catacombs listening to Maria, fears they are plotting against him and enlists the help of an inventor, telling him to give the image of the girl to his Machine Man so that a robotic Maria will destroy the belief of the workers in Maria’s holiness. The inventor takes on the character of an evil magician and constructs the robotic imitation of Maria. (There is an occult symbol, the pentagram, hanging in his workplace.) Then the film shows the devil going forth wielding a scythe, and he seems to have entered the robotic imitation Maria. This false Maria then appears as an exotic dancer that enthralls the upper-class men at a revelry, and gradually becomes more and more vividly the image of the whore of Babylon. With an evil gleam in her eyes, she then goes to the laborers to incite them to rebel against the factory owner and arouses them to destroy the machines upon which the city depends. In this part of the movie, one wonders if this is a depiction of a Marxist war of the classes. But it takes a different turn.

When the workers destroy “the Heart Machine” which controls all the electricity, the city begins to collapse and a flood is let loose. An apocalyptic scene develops. The real Maria appears and calls the children out of the buildings to bring them to safety from collapsing buildings and flooding. The son, who loves Maria, arrives to help her and is identified by her as the prophesied Mediator. In the meantime, the workers’ foreman shouts out to the workers caught up in the rebellion, “Where are your children?” The workers are suddenly distraught at the irresponsibility of their actions. They blame the false Maria and rush to capture her and burn her at the stake.

At the end of the drama, Maria inspires the son to act as Mediator and bring peace between the factory owner, the ruler of the city, who is his father, and the factory workers represented by the foreman. “Head and hands want to join together but they don’t have the heart to do it,” she says to the son. “Oh, Mediator, show them the way to do it.” So the ruling class/industrial leader as the “head” and the lower-class workers as the “hands” are united by the heart of compassion and handshake of brotherhood brought about by the son. One commentator considered the head-hand-heart trilogy as an image of the Trinity.

The film is complex, bringing together four elements: 1) an innovative and artistic visualization of the technology, scientific preoccupation, mathematical precision and massive production of modernity; 2) the human story of a father-son relationship and a love relationship between the son and the leading lady, Maria; 3) the socio-cultural depiction of a wealthy capitalist society contrasted with a depressed working class; and 4) a biblical Christian allegory of fallen man, of Satan’s evil interventions resulting in an apocalyptic disaster, succeeded by the appearance of Mary’s intercession and the redemptive resolution by the Mediator (Messiah).

The Christ-like role of the son is apparent in several ways. He lowers himself to become a factory worker in order to share their life. In one scene, he is flat against a huge machine at which he is exhausting himself and finally cries out, “Father, Father will ten hours never end?” The machine feels like the cross of Christ’s passion. The role of Maria as spiritual mother is also significant. She encourages the son to take up his  mission to be the Mediator. The son defeats the sorcerer who is carrying out the designs of Satan, trying to capture Maria and kill the son. The relationship between the father who owns everything and the son that he loves, who is mediating on behalf of the people, becomes a source of grace and peace instead of war. Interestingly, the father’s representative to his factory, Jehoshaphat, (the name of one of the good kings of Israel) who is dismissed by the father, is helped by the son and later comes to the aid of the son and Maria during the disastrous flood.

mission to be the Mediator. The son defeats the sorcerer who is carrying out the designs of Satan, trying to capture Maria and kill the son. The relationship between the father who owns everything and the son that he loves, who is mediating on behalf of the people, becomes a source of grace and peace instead of war. Interestingly, the father’s representative to his factory, Jehoshaphat, (the name of one of the good kings of Israel) who is dismissed by the father, is helped by the son and later comes to the aid of the son and Maria during the disastrous flood.

These references are not subtle in the film and the religious elements cannot be missed. However, it still could be interpreted in various ways, including as a secular humanist abstraction or as a Marxist fantasy. It is interesting that this was written in Germany of the 1920s, which was a time of challenge to Christianity, sexual indulgence in the upper class, and socialist fervor.

Fritz Lang, the film’s author and producer, was born in Austria of a Jewish mother who converted to Catholicism. He was an innovative film producer in Germany. Metropolis, based on the screenplay written by his then wife Thea von Harbou, became his most famous film. However, censors in Germany cut out major parts of it and only a greatly shortened version was available for a long time until it was recently restored with most of the original pieces. Enno Patalas worked on a restoration for 20 years and in 2002 produced “The Authorized Restored Version,” which included the original musical score. It is interesting that this film from the 1920s has come again into the light in a more complete way since the themes are

Fritz Lang, the film’s author and producer, was born in Austria of a Jewish mother who converted to Catholicism. He was an innovative film producer in Germany. Metropolis, based on the screenplay written by his then wife Thea von Harbou, became his most famous film. However, censors in Germany cut out major parts of it and only a greatly shortened version was available for a long time until it was recently restored with most of the original pieces. Enno Patalas worked on a restoration for 20 years and in 2002 produced “The Authorized Restored Version,” which included the original musical score. It is interesting that this film from the 1920s has come again into the light in a more complete way since the themes are  perhaps even more relevant today. While the industrial environment and modern work have changed since the 1920s, the concern for social justice and questions about technology are just as intense. The continuous news of one disaster after another gives rise to fear of an impending apocalypse. The spread of the occult and the satanic is vying with the Christian vision. Some of the population seems sunk in sexual and material over-indulgence, while others are struggling to survive in impoverished conditions. The science fiction medium seems well suited for reflection on the basic conflict of good versus evil in a modern technological setting. The film reminds us that beneath our social and human questions there is a spiritual drama being enacted: Christianity is continually challenged by evil forces at work that nevertheless are defeated by our Mediator Christ.

perhaps even more relevant today. While the industrial environment and modern work have changed since the 1920s, the concern for social justice and questions about technology are just as intense. The continuous news of one disaster after another gives rise to fear of an impending apocalypse. The spread of the occult and the satanic is vying with the Christian vision. Some of the population seems sunk in sexual and material over-indulgence, while others are struggling to survive in impoverished conditions. The science fiction medium seems well suited for reflection on the basic conflict of good versus evil in a modern technological setting. The film reminds us that beneath our social and human questions there is a spiritual drama being enacted: Christianity is continually challenged by evil forces at work that nevertheless are defeated by our Mediator Christ.

The images and poster are from the film, Metropolis (1927).

Written by Kathleen Curran Sweeney for The Imaginative Conservative ~ November 21, 2019