UnitedHealth Group is not an insurer, it’s a platform. And it’s in the crosshairs as Elizabeth Warren and Josh Hawley propose breaking it apart, severing its pharmacy arm from the rest of the business

…ANGER at Health Care industry!

The saga of the UnitedHealth Care CEO assassination has, as could be expected, now turned into a discussion of our health care system. Elizabeth Warren, for instance, is making the obvious point that people hate the health care system.

Then, productively, she proposed, along with Republican Senator Josh Hawley, legislation to split apart some of these monster companies from their pharmacy subsidiaries, thus reducing conflicts of interest in health care. While this legislation was in the works long before the killing, it didn’t stop Wall Street investors from saying that any discussion of health care reform was a de facto endorsement of murder.

These kinds of discussions are always done in bad faith, since people who make a lot of money from killing people with spreadsheets like to pretend to be very offended when anyone points out health care is a matter of life and death. That said, moral hypocrisy isn’t the primary reason our health care system is so problematic. A more important objection to reform is from a certain dominant strain of thinking among economists and health care wonks, who question whether the health insurers are really that bad. Economics blogger Noah Smith epitomized this view when he wrote a piece titled “Insurance companies aren’t the main villain of the U.S. health system.”

Anger at insurers reflects, in his word, “deep-seated popular misconceptions about the U.S. health care industry. A whole lot of people – maybe even most people – seem to regard health insurance companies as the main villains in the system, when in fact they’re only a very minor source of the problems.” In other words, insurers are hated not because they do bad things, but because they do something that is necessary: rationing.

Doctor And Patient

In fact, he says, the actual villains are the people taking care of you, the “smiling doctor” who knows the price but won’t tell you upfront. “So you get to hate UnitedHealthcare and Cigna,” Smith says, “while the real people taking away your life’s savings and putting you at risk of bankruptcy get to play Mother Theresa.” These doctors and nurses hire insurers for a modest fee in return for appearing like the bad guy, while the caregivers laugh all the way to the bank.

Smith sees this misconception as borne of our experience with the system. Doctors, nurses, technicians – what he problematically lumps together with a broader category of corporate “providers” – take care of us, so we like them, whereas insurers are just paper pushers, and so we react negatively. Yet it’s the “providers,” Smith notes, who generate most of the waste and profit. Insurers, by contrast, hold down these costs. Anger at UnitedHealth Group is just a big misunderstanding. The true villain, he says, is the doctor. (Eric Levitz of Vox, which as it turns out is financed by the health insurance industry, also argued that greedy doctors are the true problem, as does Biden supporter and pundit Matt Yglesias.)

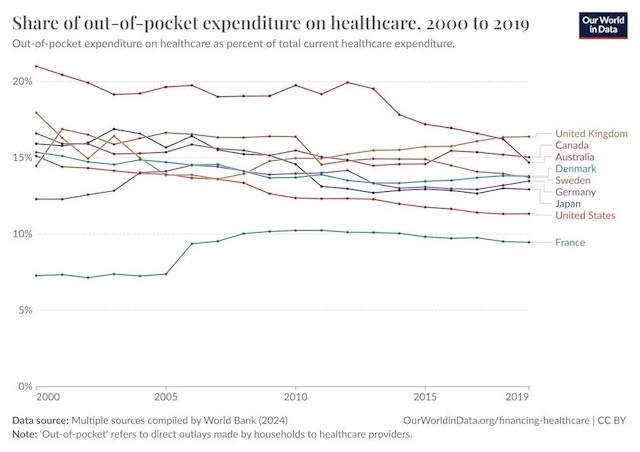

To support this view, Smith makes a couple of points. First, he argues insurance just isn’t very profitable. UnitedHealth Group has a profit margin of six percent, which is half of the margin of normal public companies. The company makes a lot of money, with a net income of $23 billion in 2023, but that’s small compared to the $371 billion in overall revenue, $241.9 billion of which, he says, is paid out in medical costs. Second, out of pocket expenses are lower percentage-wise than what people in other countries experience. He puts this chart up. We don’t pay more more out of pocket percentage-wide, it’s just the level of cost is far too high, because of ‘providers.’

Matt Bruenig does an excellent job of showing why Smith’s numbers are off (though his ‘single payer or bust’ framework is unnecessary, as there are many nations without single payer who nonetheless have much lower waste). One obvious problem with Smith’s analysis is that accounting profits are a dumb way to understand surplus spending. A far better way is just to look at administrative bloat. In 2020, one study showed that 34% of American expenditures on health care was spent on administration, about $2497 per capita, versus $551 in Canada. There are plenty of other studies illustrating high administrative burdens.

Matt Bruenig does an excellent job of showing why Smith’s numbers are off (though his ‘single payer or bust’ framework is unnecessary, as there are many nations without single payer who nonetheless have much lower waste). One obvious problem with Smith’s analysis is that accounting profits are a dumb way to understand surplus spending. A far better way is just to look at administrative bloat. In 2020, one study showed that 34% of American expenditures on health care was spent on administration, about $2497 per capita, versus $551 in Canada. There are plenty of other studies illustrating high administrative burdens.

That said, administrative bloat and excess profits, though massive, understate the problem, because even where there technically isn’t waste, American medicine, according to doctors, is getting even more bureaucratic. I want to focus on some of the history of health care reform, and explain the conceptual flaws at the heart Smith’s views, because they are not some isolated fringe perspective. His formulation of the problem in health care – who is to blame, and how we should fix it – are widely held across the political aisle among health policy types and economists who have designed our health system of the last number of decades, including Obamacare.

Everyone agrees on the basic problem with U.S. health care, which is that we spend too much and have poor outcomes. The disagreement is about why. Smith thinks the heart of the health care problem is that Americans over-consume, due to “moral hazard.” We get a tax-break to buy health insurance, which we pay in premiums, but we don’t pay at the counter when actually getting services. It’s like paying upfront for an all-you-can-eat buffet, you then have an incentive to take as much care as possible. And doctors have an incentivize to over-order it because they are paid under the much-maligned “fee for service” model. In that model, clinicans were paid per service – an office visit, a x-ray, a procedure. But that led, in the “over-consumption” way of thinking, to waste.

Skin the Game: Deductibles and Copays

Economists, seeing this moral hazard, sought to fix it with high-deductible plans, designed so we’d have “skin in the game” and have to pay each time we want to consume a service that we already bought through premiums. But it wasn’t just patients who needed skin in the game–the clinicians, especially doctors, also needed skin in the game to correct the misaligned incentives of fee-for-service.

This theory of overconsumption dates back decades, most notably to the rise of “managed care” in the 1970 and 80s. To contain over-utilization through the private sector, the idea was to empower insurance companies through the rise of health maintenance organizations, or HMOs. These organizations would pursue business tactics that restrict how much patients use the health care system; this was and is still called “utilization management.”

These practices included “network design,” or what we know as having doctors out of our network, so we can’t see them. They also included “benefit design,” which is what I describe above: high copays and deductibles so we use less care. Then there were the mechanisms to control doctors, prior authorization being the big one. The other was known as “capitation” or “risk bearing.” The idea was to have physicians assume the function of an insurance company. Instead of paying per service, insurance companies would give physician groups or a hospitals a lump sum budget, hoping physicians would better manage utilization because they could turn a profit by minimizing services delivered. Managed care spurred a wave of hospital and physician consolidation in the 90s, and caused massive backlash from clinicians and patients, who were against this sort of rationing from insurance companies.

Despite this backlash, as Hayden Rooke-Ley describes it, policymakers would double down on managed care in our public programs, Medicare and Medicaid. The idea, again, was to break from the fee-for-service model. The Bush Administration in 2003 was the first to make a major move in this direction by trying to expand the privatized version of Medicare, which he renamed to “Medicare Advantage.” As Rooke-Ley tells it, was an attempt to import HMOs into Medicare. The government would pay for care as a basket of services in one lump sum for a patient. Instead of the fee-for-service model, where Medicare would pay physicians for each service, Medicare would pay a private insurance company to manage the costs of patients. What the insurere didn’t spend on care, they kept as profit. Two decades later, this would become a $500 billion dollar Medicare Advantage program, in which the government cuts a check of more than $100B annually to United Healthcare.

Value-Based Care and the Doctor’s Pen

As Rooke-Ley describes, when the Democrats took over in 2008, they would embrace the theory of managed care, but they would implement it differently, and call it by a new name: value-based care. And that gets to why Obamacare, aka the “Affordable Care Act,” was designed the way it was. The “overconsumption” thesis was put forward in one of the most influential articles in American health care history, Atul Gawande‘s 2009 piece in The New Yorker titled “The Cost Conundrum” that articulated the rationale behind the ACA. In it, Gawande argued that Americans spend too much on health care because doctors over-order it. “The most expensive piece of medical equipment, as the saying goes, is a doctor’s pen,” he wrote. It is the “accumulation of individual decisions doctors make” that drive health care costs. “And, as a rule, hospital executives don’t own the pen caps. Doctors do.”

The obvious way to fix this dynamic would be to publicly ration care. Another way to do this would be to expand the existing system of private rationing through insurance companies, ie standard managed care. But policymakers were wary of the backlash to managed care and burned from the 1990s-era battles over so-called HillaryCare, which effectively sought to put everyone in a managed care HMO and have these insurers compete through “managed competition.” They needed a different way of private rationing of utilization. So they needed to hide the rationing. And that’s what they did. In 2009, for instance, economist Doug Elmendorf, a major player in policy debates, testified to Congress as to the reason health care costs were so overwhelming in America. He said it explicitly.

Given the central role of medical technology in the growth of health care spending, reducing or slowing that spending over the long term will probably require decreasing the pace of adopting new treatments and procedures or limiting the breadth of their application. Such changes need not involve explicit rationing but could occur as a result of market mechanisms or policy changes that affect the incentives to develop and adopt more costly treatments.

Elmendorf makes two claims here. The first is that health care spending is happening because of over-consumption of health care treatments, largely based on research in the 2000s from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care showing that there was hundreds of billions of dollars of waste in the system to cut out –the same ones that Gawande relied on in his thesis.. The second is that to address this problem, you need to ration, but not explicitly ration. You have to do it through “market mechanisms.” Now, I’ll leave aside that Americans might be angry about being misled by passive aggressive policymaking, even if they didn’t know exactly how, and just point out that the goal of Obamacare was not just to expand insurance to the uninsured, but to more assertively ration care for those who already had it. (And yes, there’s probably a joke in here about capitalism good communism bad.)

ObamaCare: “Bend over. I’ll drive!”

The result, as I mentioned, was the expansion of value-based care, the new name for the reimbursement mechanism that market-obsessed champions of the 80s and 90s sought to promote. The idea was to correct the bad incentives of physicians by paying them not per service, but instead having them assume the insurance function. If doctors could limit how much patients used the health care system, and resist their own greedy impulses to provide too much care, then they could profit. This is what Elmendorf meant by “market mechanism.” Though this sort of contracting had receded with the backlash to managed care, it was occurring in the growing Medicare Advantage market. With the expansion of value-based care, the idea was to transform all of health care toward this sort of payment model, starting with regular Medicare, which remained the largest “payer” of healthcare services nationally.

And value-based care had a logic to it. The Republican-led managed care theory dealt with the “moral hazard” of patients by empowering insurance companies to restrict care options and make patients put more skin in the game. To deal with the moral hazard of physicians, we needed to transfer some of the insurance function–that skin in the game – to them. With the right economic incentives, they would ration total use of case, driving down costs. What this meant in reality was hospitals, private equity, and insurance conglomerates would be empowered to control physicians and other clinicians, because doctors couldn’t assume this insurance function on their own. Indeed 80 percent of doctors are now employed by one of these corporate entities. UHG is not only the largest insurer, it is the largest employer of physicians. And it is the foremost champion of doing value-based care, which one of its executives recently described as as the new era of medicine is which physicians are no longer in charge. That’s what all of these managed care reforms have amounted to, ways of putting friction between the patient and medicine.

This all seemed reasonable, because care was too affordable for patients, so they overused it, and physicians got paid for each service, so they delivered too much of it.

This view wasn’t bad faith. Obama honestly believed Gawande, the Dartmouth work, and all the people who said that there’s just a lot of waste that should be easy to cut. That’s why he promised that you could keep your doctor, and that families would see lower premiums by an average of $2500. But here’s the thing. None of it worked to slow the cost of care. The “Affordable Care Act” didn’t make health care affordable, you couldn’t always keep your doctor, and costs kept going up. What happened?

It’s the Prices, Stupid

It turns out the reason health care costs kept going up despite the reforms meant to reverse the trendline is because policymakers misdiagnosed the underlying problem. The Dartmouth work was just wrong on overuse of medicine. Higher medical costs in America were result of, you guessed it, monopoly power.

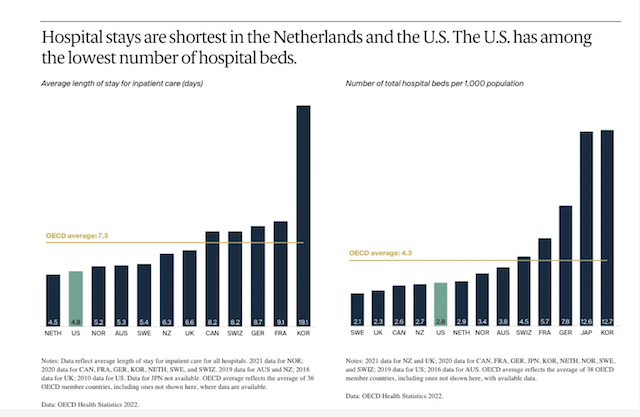

In 2003, four scholars published a famous article titled It’s the Prices, Stupid, finding the U.S. pays more and consumes less on health care than peer countries. Though we spend twice as much, the U.S. has fewer doctors per capita, fewer hospital beds per capita, and among the shortest hospital stays than other rich nations. We just pay more for what we get. These scholars reran the study in 2019, after various reforms, and found the problem was the same. Embedded in the prices for services, as Breunig notes, are staggering administrative costs.

It wasn’t just that policymakers fundamentally misdiagnosed our health care problem. They also made another grievous error, and that was the way they thought about doing rationing. They didn’t say “we’re going to have a board of doctors make decisions about what care can happen for what disease and what this will cost,” which would be a public utility model. Instead, managed care meant private rationing through consolidation.

It wasn’t just that policymakers fundamentally misdiagnosed our health care problem. They also made another grievous error, and that was the way they thought about doing rationing. They didn’t say “we’re going to have a board of doctors make decisions about what care can happen for what disease and what this will cost,” which would be a public utility model. Instead, managed care meant private rationing through consolidation.

RELATED: Hospital Where Student Nurse Died of Sepsis Had Lack of Beds

They took hospitals, insurers, pharmaceutical middlemen, and doctor’s practices, and put them under the thumb of financiers through waves of acquisitions. Putting hard-hearted bankers in charge, and saying you get to make money if you reduce waste, was a seemingly cruel but necessary approach to the problem. Indeed, if you notice a certain meanness to Smith’s argument, the kind of casual cruelty we so often see with status quo defending thinkers, that’s where it comes from. You want me on that wall, you need me on that wall, or grandma’s gonna get an expensive heart surgery that won’t help her but that all of us will have to pay for.

The result was waves of consolidation in every aspect of the system, from hospitals to drug stores to emergency room physician services. In February of 2020, I did a detailed analysis of the rise of CVS, showing that over a series of mergers, the firm rolled up pharmacies, pharmaceutical middlemen, urgent care clinics, and insurers. UnitedHealth Group, between 2021-2023 alone, gained control over 1,300 new companies. Now, anyone who knows anything about monopolies can tell you immediately what would happen when an industry gets consolidated. Prices go up, output goes down, and quality gets worse. And that’s what happened.

GREED!

Yes, there are significant profits throughout the health care system, but the true way that the monopolization shows itself is through administrative overhead. Medicare Advantage, with its fancy capitation through monopolists like UnitedHealth Group, requires more than $100 billion a year more than just regular Medicare in overpayments. That’s a lot of money. But this kind of waste is everywhere; the top three pharmacy benefit managers in America, who are basically just firms who manage spreadsheets, have more revenue than France spends on health care.

The point is that it’s not “smiling doctors” who want to charge high prices for a hospital visit causing our problem; as I mentioned, these doctors are largely just employees now, working for an insurance company or a hospital or a private equity firm. And this is illustrates the error when Smith refers to “providers” as the doctors and nurses., With corporate consolidation on both the provider and insurance side, what results is massive administrative overhead and price gouging, a red queen’s race where every big company is investing in administrative bloat to fight with every other big company, often with perverse spending outcomes that lead to crazy amounts of waste in some areas and a total lack of care in others. And the idea that doctors know what a price of an operation or procedure might be implies that there is a single price. But there isn’t. A drug or procedure for one patient could be five times as expensive for someone else, depending on their plan or other factors.

The Platformization of Health Care

And that gets to the final conceptual problem. Smith might argue, well, sure there’s waste, but most of that isn’t in the health insurance sector, it’s in other areas of the health business. But that’s an outdated way of thinking. Over the past twenty years, we have smooshed together lines of business in health care such that there is no such thing as a pure “health insurer” anymore. As I noted, United is the largest physician employer and the nation’s leader in value-based care. It’s like calling Google an email company. Sure it owns and runs Gmail, but it’s much more than that.

To understand why this view doesn’t make sense, it helps to start with some antitrust cases. The Biden Antitrust Division’s first merger challenge was UHG buying payment network Change Health in an $8 billion dollar deal. As I noted, that merger was a catastrophe; a year after the DOJ lost and the deal closed, Change got hacked and hospitals, doctors, and pharmacists lost access to cash flow, allowing UHG to buy up some of the providers it had crippled.

But that’s not the only challenge. In mid-November, the Antitrust Division sued UHG over its $3.3 billion dollar attempted acquisition of home health care and hospice provider Amedisys. So the first and last merger cases by Biden were both against UHG. And that’s not all, the Federal Trade Commission also sued UHG over its manipulation of drug pricing through its pharmacy benefit manager arm. Here’s a report released just before the lawsuit showing what these PBM subsidiaries did, according to one high-level executive.

“We’ve created plan designs to aggressively steer customers to home delivery where the drug cost is ~200 times higher,” he wrote. If you went to Costco, he went on to say, the cost was $97, so the plan didn’t recommend patients go there. If a patient went to Walgreens, which the plan did recommend, it was $9000. And if a patient chose home delivery via the PBMs own mail order pharmacy, it was $19,200. “The optics are not good and must be addressed,” he added. He didn’t need to say that the added revenue for PBMs, just for that one drug, was $902.1 million over a few years.

So UHG has been under a lot of legal heat. But notice something about these lawsuits? None of them have to do with health insurance. UHG was sued over its manipulation of drug pricing, for buying a financial company, and for trying to acquire a bunch of medical caregivers.

UHG, in other words, is not primarily a health insurer, but something new. It is the biggest employer of doctors in the nation, it has a significant software business, and it sits in the middle of the pharmaceutical pricing chain with its OptumRx pharmacy benefit manager and giant mail-order pharmacy. In 2020, when the U.S. government delivered tens of billions of dollars to hospitals, guess what financial conduit it used? Optum Bank, which is also owned by UHG. And it is now in the pharmaceutical production business, as is CVS.

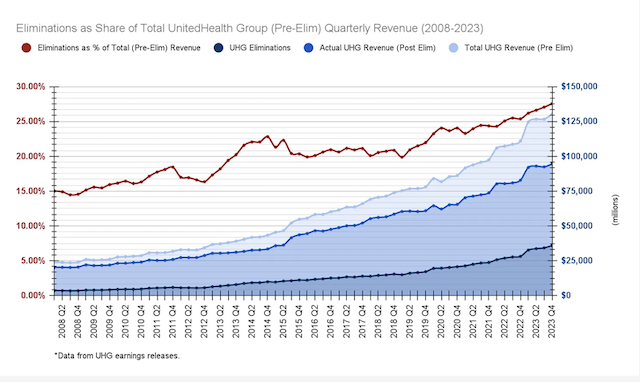

UnitedHealth Group isn’t, as Noah Smith believes, spending $241.9 billion paying for medical costs, it is trying to figure out how to use that money from UnitedHealth Care – its insurance arm – to buy from Optum – its arm of everything else. UHG even has a term for this spending, ‘intercompany eliminations,’ which have now reached 27% of its revenue.

The data shows that UnitedHealth’s inter-subsidiary business dealings have been growing as a share of its total revenue over time, almost doubling over 16 years from about 15% in 2008. This means that UnitedHealthcare insurance plans are not only increasingly paying to use Optum’s physicians, PBM, claims integrity processing and revenue cycle management, but that UnitedHealth’s overall growth appears to be dependent on these kinds of internal transactions.

A lot of what UnitedHealth Group is doing with the money that Smith thinks is paying for health care is simply self-dealing.

This model is new. In the 2000s, we used to have health insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, doctor’s practices, software firms, and payment networks, and they were all independent and traded with one another as need be. There were a few exceptions – Kaiser was both an insurer and hospital network, but for the most part, a health insurer made money selling health insurance, a doctor made money selling his services, et al. Today, we have UnitedHealth Group and CVS, which are trying to take a piece in every part of the health business.

The mashing together of health lines of business is something prompted by the Bush-era changes in Medicare in the early 2000s, and then the creation of Obamacare, which, in addition to the value-based care reforms, capped profits for insurers but still allowed those insurers to buy providers. Because of this profit cap, known as the “medical loss ratio,” insurers could only make a certain amount of money through health insurance, but they could take their patient money and spend it on doctors they employ using software they sold financed by a bank they owned. And now, they do. I wrote this up in a piece about how Obamacare created big medicine.

A profit cap like the Medical Loss Ratio is generally a good thing for utility businesses, but such regulations must be paired with a prohibition on expanding outside of a simple line of business. Otherwise, you get massive conflicts of interest. And that’s where economists, who think certain forms of corporate consolidation are efficient and that conflicts of interest don’t much matter, came into the picture. FTC economists validated the smooshing together of certain lines of business, seeing a pharmacy benefits manager owning its own mail order pharmacy, which UnitedHealth Group does, as beneficial, instead of dangerous.

Some policymakers have noticed this business model shift. Last month, Antitrust AAG Jonathan Kanter gave a speech on the platformization of health care, noting that we have to stop thinking about health care giants as insurers, providers, PBMs, or doctors practices, or hospitals. They are, as he noted, all of the above. They are in many ways tech platforms, like Google owning a search engine and steering people to its other products with that. These health conglomerates have mimicked this strategy. CVS in 2018 even called itself a “uniquely powerful platform,” bragging that it touched a third of Americans with its drug store chain, Aetna insurance company, urgent care clinics, and PBM. Kanter called the problem “health care Tetris.”

And this dynamic isn’t just a function of insurers buying up and down the value chain. Everyone is smooshing together. In Pennsylvania, giant hospital systems are taking over the insurance industry, drug distributors are buying oncology clinics, and even Kaiser – perhaps the only integrated system that actually delivers real integrated care – is expanding into a more assertive financialized model. Here’s a list of the top twenty corporations in America by revenue. Seven are health conglomerates, all of which have many different lines of business.

It’s much worse than just one insurance company integrating into an octopus, all parts of the system are being systematically corrupted by conflicts of interest. For instance, take an example I heard recently. Oncologists at smaller practices are willing to try really new drugs because they know the research and know it is the best drug for the patient’s disease. But oncologists at practices owned by big distributors are often robotic and compliant, prescribing from a list of drugs, known as a ‘formulary,’ handed down from their employer, drugs that are more likely to make money for the distributor parent. To get to the ideological point, such formularies are explicit rationing mechanisms, and the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committees that design them are effectively death panels (though they’d never think of themselves in that light).

It’s much worse than just one insurance company integrating into an octopus, all parts of the system are being systematically corrupted by conflicts of interest. For instance, take an example I heard recently. Oncologists at smaller practices are willing to try really new drugs because they know the research and know it is the best drug for the patient’s disease. But oncologists at practices owned by big distributors are often robotic and compliant, prescribing from a list of drugs, known as a ‘formulary,’ handed down from their employer, drugs that are more likely to make money for the distributor parent. To get to the ideological point, such formularies are explicit rationing mechanisms, and the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committees that design them are effectively death panels (though they’d never think of themselves in that light).

But even putting aside the conflicts, value-based care itself increases administrative costs by an enormous margin. There are entire industries devoted to coming up with metrics (NQF, PQA, etc), there’s a ton of coding inside of electronic health records to be able to measure those metrics (which creates a health record monopoly called Epic Systems), and there’s staff inside hospitals and clinics and insurers to track everything. Value based care’s administrative complexity also makes it impossible to have a small practice, you have to be part of a large enough group that the measurements can be statistically meaningful, so you get “clinically integrated networks” of bigger doctor practices. As one person told me:

The amount of time I have personally observed people (including clinicians and administrators) spending on VBC stuff is insane. It consumes SO much time and effort- it might be meaningful; it might not be, but it definitely contributes to administrative overhead.

Add to that the fact that we live in a multi-payer system where every single payer has different metrics they want to focus on for your bonus, and the admin becomes mind bogglingly huge. UHC wants you to work on readmissions, Aetna wants you to work on hospital acquired infections, Cigna wants you to work on getting people to get their prescriptions in 100 day supplies, and Centene wants you to get all of the people with asthma to have an action plan.

In other words, we have large unmanageable bureaucratic nightmare corporations negotiating with each other across endless lines of business, along with un-trackable flows of money and opaque pricing. These corporations in turn create a sort of cartel of giants, the way Google and Apple cut a deal to split search profits. That’s why Americans feel like we’re a bizarre financial system where care is almost incidental, and clinicians and patients are frustrated.

What Is to Be Done?

Ultimately, as Rooke-Ley observes, the solutions are pretty straightforward. Policymakers need to stop micromanaging clinicians and patients in pursuit of less use of health care, and move power back to clinicians and their patients, and out of the hands of bankers. We have to see health care as public infrastructure. We already see the world this way; emergency rooms have to take all comers. And 70% of healthcare is already financed through the government, which is more than any other country spends.

It’s not that profit is bad, or that we need a specific form of public or private payment. Any model can work. But we have to eliminate bargaining power and conflicts of interest as the key strategic goals among health care executives; that’s the premise of the Hawley/Warren bill to split off pharmacies from the rest of the health conglomerate. Let’s go further and do it across the board, forcing firms to divest lines of business that create conflicts of interest. We also need publicly available, clear prices where people pay the same price for the same good or service, as Indiana Republican Senator Jim Banks suggests for hospitals. If we can put those incentives in place, then a lot of these companies will split themselves apart, since it won’t be worth it to be a large inefficient conglomerate.

We also have to re-conceptualize the idea of the health care “business.” The amount of financial bullshit in this part of the economy is insane, and fake entrepreneurs are constantly spreadsheet jockeying for money. So on a basic level, if you’re not producing medicine or dealing with patients, you should probably be employed by the government or in an administrative role making very thin profit margins. These are lives we’re talking about.

To conclude, Smith’s argument is flawed, but more importantly misses the point. The public isn’t wrong to hate these giant conglomerates. These are the firms that have power of life and death over us. And there are many reasons to see UnitedHealth Group as a particularly noxious corporation, because it reaches into every part of the health business, and has lobbying and political power designed to thwart a public-minded system. But ultimately, it’s not just UHG. In fact, UHG’s existence is a result of sloppy thinking among health policy wonks and economics-minded people who haven’t followed the industry. And we ought to start by correcting that.

Written by Matt Stoller for the BIG Newsletter ~ December 12, 2024

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www. law. cornell. edu/uscode/17/107. shtml