Why are politics so consumed with the past?

In the fall of 2017, the journalist and poet Clint Smith began to visit sites that held some poignant meaning in the history of American slavery: the human shipment point of Gorée Island, in Senegal; the Whitney Plantation, in Louisiana, where an 1811 slave rebellion is commemorated; Galveston Island, in Texas, the site of the original Juneteenth liberation; and Monticello. Smith’s travels, which he recounts in a new book, “How the Word Is Passed,” began just a few months after the white-nationalist uprising at Charlottesville: the conservative defense of the Confederate monuments was a live political issue, and the reckoning with the racial past seemed to him both under way and partial. “It seems that the more purposefully some places have attempted to tell the truth about their proximity to slavery and its aftermath, the more staunchly other places have refused,” Smith writes.

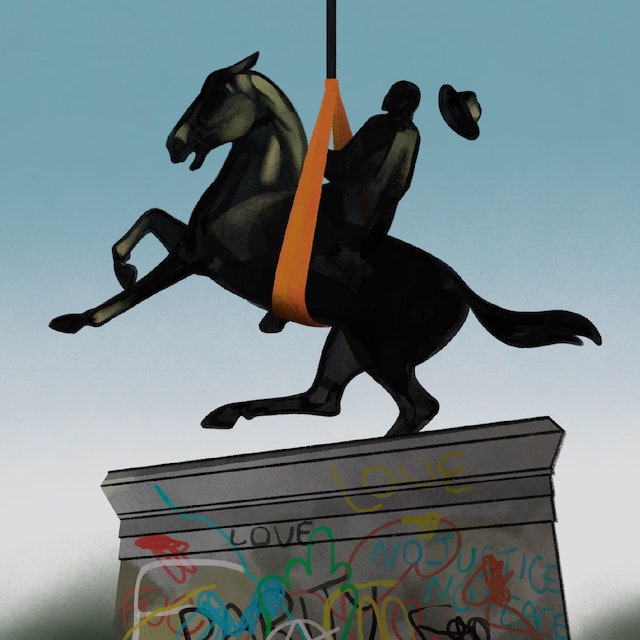

Though Smith sets a chapter in Manhattan, where he visits the site of a slave-auction block, and a chapter in West Africa, his book is mostly about the American South, during a period when the South’s political identity has begun to change. The South is still a conservative place, but election analysts no longer need a special regional element to explain its voting behavior: Democrats do better in states, like Virginia and Georgia, that have large numbers of Black and college-educated white voters, and worse in places that don’t. The outrage of conservative state legislatures over social-studies curricula involves concession that school boards from Texas to North Carolina have embraced a progressive view of history and current events. The most significant Confederate monuments—those on Richmond’s Monument Avenue and Stone Mountain, near Atlanta—are either being removed or might soon be. “The whole ideology of the Lost Cause is in deep trouble,” David Blight, the eminent Yale historian of the Civil War and its aftermath, told me earlier this week. “The fact that Monument Avenue is being taken apart is something that no one in my field truly thought they would ever see.” Even more striking to him are the deep discussions under way about reimagining Stone Mountain, with its ninety-foot-high carvings of Confederate leaders. Blight said, “In my field, we’ve had conference after conference and talk after talk about the Confederate monuments and everyone always says, ‘Well, Stone Mountain, they’ll never be able to take that down.’ ” But now they might. For generations, conservative Southern politicians had openly defended the Confederate cause. Blight said, “Republicans just don’t go there.”

As Smith travels this changing South, he finds memorials to slavery that exist alongside, and in some cases have displaced, the old monuments to the Lost Cause. As a narrator, Smith is patient and gentle-mannered, and when he visits plantations and battlefields he is drawn to the people who are there with him in the present day: reënactors, tourists, and, most of all, curators and tour guides, whom he tends to engage in long and thoughtful conversations. In Smith’s home town of New Orleans, an older Black activist named Leon A. Waters shows him a historical marker that explains the city’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. Waters says, of the marker, “It’s doing its job.” Every day visitors come, read, take pictures, learn. An hour upriver along the Mississippi, Smith visits the Whitney Plantation, now a museum to the experience of slavery, where fifty-five ceramic sculptures, depicting the heads of slaves executed for taking part in the rebellion that began in the area, are displayed on silver rods. The museum’s head of operations, a Black woman named Yvonne Holden, shows Smith the large metal sugar kettles that slaves once used to boil down juice from cane. The display, she tells him, gives tour guides an opportunity to prompt visitors to think about the role of the North in sustaining slavery—the sugar cane was sent to Northern granulation facilities. “And the North,” she added, “where were they getting that cotton from?” Visiting the plantation and a bare cabin that, until 1975, had been occupied by descendants of those who had been enslaved at the Whitney Plantation, Smith recalls that the corpses of the enslaved were sometimes shipped North for scientific study, “constantly being exploited at every age, even in their death.”

Smith writes about the durability of history, but his emphasis, so in keeping with the mood of progressives in 2021, is on how much people have changed. At a Juneteenth commemoration in Galveston, Smith finds himself unexpectedly moved when a multiracial crowd launches into “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and a white reënactor, playing the role of the Union general Gordon Granger, read the federal order announcing the end of the slavery. The reënactor, Stephen Duncan, recalled the first time he read the proclamation aloud. It was “absolutely overwhelming,” he told Smith. The script called for Duncan to say, “All slaves are free. Let me say it again. All slaves are free.” That, he said, “has got to be the most powerful four words in human history.”

Not all of the sites Smith visits are like Galveston. At Blandford Cemetery, in Petersburg, Virginia, the site of a mass grave of some thirty thousand Confederate war dead, Smith encounters a celebration that leans toward Lost Cause heroizing. Ever empathetic, he concludes, “For many of the people I met at Blandford, the story of the Confederacy is the story of their home, of their family—and the story of their family is the story of them.” No wonder they have been so resistant to “confront the flaws of their ancestors,” he writes. At Blandford, Smith watches a Confederate honor guard solemnly present, and listens to the crowd singing a “spirited rendition” of “Dixie.” That is still a sound you can hear, if you want to seek it out.

But it is getting harder. The most affecting scene in Smith’s book is set at Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, now perhaps nearly as well known as the home of Sally Hemings, the enslaved woman who had at least six children with him. On his visit, Smith finds that the history of the Hemings family has come to define the official presentation of Monticello. Smith’s tour guide is a white Navy veteran named David Thorson, who tells a story about Thomas Jefferson making a birthday gift to his children and ends it with a hammer: “Those presents were human beings.”

Smith is somewhat wowed by Thorson. “It’s not that this information was new,” he writes, “it’s that I had not expected to hear it in this place, in this way, with this group of almost exclusively white visitors staring back at him.” Smith talks at length with a pair of older white women, named Donna and Grace, who tell him they are Republicans. They, too, have been thrown for a loop. Speaking of Jefferson, Donna tells Smith, “You grow up and it’s basic American history from fourth grade. . . . He’s a great man and he did all this. And, granted, he achieved things. But we were just saying, this really took the shine off the guy.” Grace agrees, and says, of Thorson, “This man here just opened a whole new avenue to me.”

For many generations, white Northerners treated the white Southern experience with an excess of politeness. If white Southerners’ relationship with their history was, as Smith put it at Blandford, a “family” story, then white Northerners would behave as if we were in someone else’s house, and avoid questioning local prerogatives. That deference, and the deceitful monuments and histories to the Confederacy that it allowed, also had the effect of “Southerning” American racial cruelty. From the Northern perspective, the history of the United States could be split into two experiments: one of them agrarian, oligarchic, nostalgic, dependent first on chattel slavery and then an explicit racial hierarchy, and broadly failed, and the other urban, capitalistic, democratic, defined by irregular progress toward racial equality, and essentially successful. But the South no longer seems so exceptional, or peculiar, in its economy or its politics. And as a public history of the enslaved and their descendants has developed, it has included some reminders—like the sugar kettles at the Whitney Plantation—that even in its racial cruelty this was always one experiment, not two.

In a striking essay in the July issue of Harper’s, the Princeton historian Matthew Karp considers the uproar over the 1619 Project—first a special issue of the Times Magazine, and now a history curriculum, which argues that the country’s defining moment was the importation of African slaves, and traces contemporary phenomena, from the racial wealth gap to differences in health care to the structure of highways in Atlanta, back to that point of origin. Conservative politicians have loudly denounced the 1619 Project (thirty-nine Republican senators, led by Mitch McConnell, called it “debunked advocacy” in a letter to the Secretary of Education) but it has also faced some more substantive criticism from a group of liberal historians, among them Sean Wilentz of Princeton, who have argued that it overstates the degree to which the Founders were motivated by a desire to protect the institution of slavery. Karp’s critique follows a somewhat different line, arguing not that the 1619 Project misleads on the facts but that its point of view is as essentialist as the one that insists on a heroic American trajectory blossoming from the vision of the Founding Fathers. In both cases, he writes, history “is not a jagged chronicle of events, struggles, and transformations; it is the blossoming of planted seeds, the flourishing of a foundational premise.” Karp focusses on the language of the 1619 Project: slavery is described as America’s “original sin”; racism as part of “America’s DNA.” Karp writes, “These marks are indelible, and they stem from birth.”

Unlike the liberal historians who have applauded the removal of monuments and the revision of public memory, Karp argues that the history war represents a diversion from the more pressing and material problems of the present—he mentions that the Democratic legislators who now run Virginia refused to repeal the state’s right-to-work law even as they approved a celebration of Juneteenth, and suggests that the eagerness to revise the past may be connected to a reluctance to reimagine the present. “Leaving behind the End of History,” Karp writes, “we have arrived at something like History as End.” Surely there’s something to this—it was pretty rich to see so many Republicans on Capitol Hill rushing to commemorate Juneteenth even as conservative state legislatures around the country passed bills restricting access to the ballot. But it gives a very large role, maybe too large a role, to liberals. Conservatives have more often been the political protagonists of the history wars, insisting that an ideology of critical race theory was at work in education curriculum that Democrats would have preferred not to discuss at all, and forming a reactionary politics around the defense of Confederate monuments. If the question is why there is so much political debate about our national origins right now, one answer might be that the changing South and the emerging public history of slavery and its aftermath mean that racial oppression can no longer convincingly be described as primarily a regional phenomenon.

If all goes according to plan, some significant changes to the public squares of the South will take place this summer. The Confederate memorials in Charlottesville can be removed as early as July 7th. (At the recent city-council meeting devoted to the matter, the nonprofit journalism outlet Charlottesville Tomorrow reported, “no one spoke in opposition to the statues’ removal—with adjectives like ‘toxic waste,’ ‘bastions of hate’ and ‘poisonous propaganda’ used to describe them.”) Officials in Richmond have announced plans to remove the remnants of all of the Confederate memorials on Monument Avenue. (There have been delays in the removal of the monument to A. P. Hill, owing to the grisly fact that Hill’s remains are buried underneath, but that one is coming down, too.) A Virginia without these monuments is a different Virginia; a South without the Richmond memorials or Stone Mountain would be a different South. But the removals, and the erosion of a Southern exceptionalism they make evident, also make way for something complicated and contested—a slightly different country, one with more blame to go around.

Written by Benjamin Wallace-Wells for The New Yorker ~ June 24, 2021