Americans are united on this: They are sick and tired of being so divided.

The divisive national debate over just about everything has convinced many that the country is heading in the wrong direction even as their own lives are going well, the inaugural Public Agenda/USA TODAY/Ipsos poll finds.

By overwhelming margins, those surveyed said national leaders, social media and the news media have exacerbated and exaggerated those divisions, sometimes for their own benefit and to the detriment of ordinary people.

More than nine of 10 – about as close to unanimity as a national poll usually reaches – said it’s important for the United States to try to reduce that divisiveness. Figuring out how to have a constructive conversation with folks on the other side would be a good start, most said.

“The hardest thing with the climate in the government is, you turn on the news, they can’t even sit down and have a discussion; they can’t work out anything,” said Lynn Andino, 53, a nurse and political independent from New Rochelle, in the New York City suburbs. “They storm out; this one said that; it’s tit-for-tat; I’m going to throw mud at you; you’re going to throw that mud back. It’s like they can’t even work on anything.”

The findings from the Public Agenda/USA TODAY/Ipsos poll, and focus groups convened in New Rochelle, Cincinnati and Jackson, Mississippi, launch an election-year project by USA TODAY and Public Agenda, a nonpartisan research organization. The Hidden Common Ground initiative will explore areas of agreement on major issues facing the nation and also spotlight how local communities have worked across divisions to solve problems.

The project, in partnership with the Kettering Foundation, is supported by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Charles Koch Foundation and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund.

The online poll of 1,548 adults, taken Oct. 14-21, has a margin of error of plus or minus 2.6 percentage points.

Suspicions run deep

The findings illuminated both the opportunities and the hurdles in trying to foster a less toxic public debate. For one thing, the suspicion of each side about the other was deep.

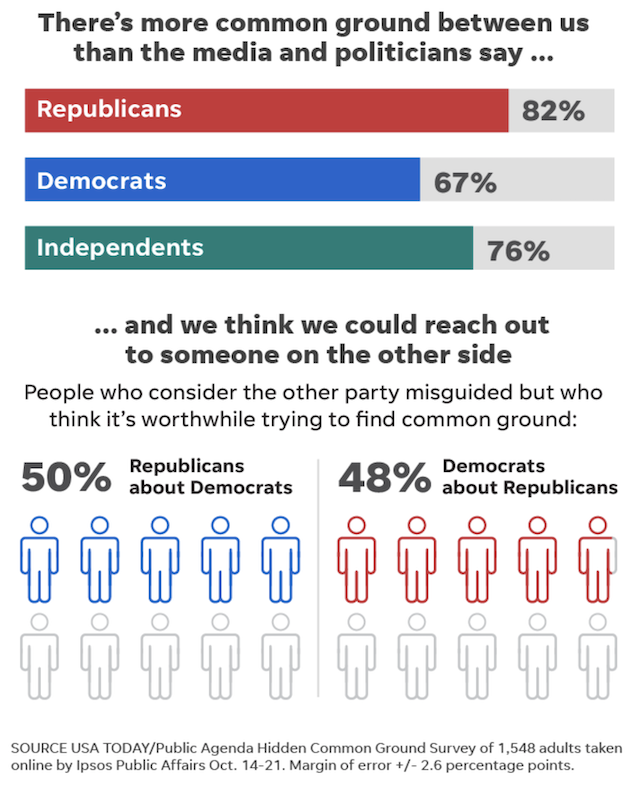

Both Republicans and Democrats estimated that just over half of those in the other party were “so extreme you can’t imagine finding common ground with them.” (There was some surprising bipartisan accord on that: Democrats and Republicans each said that more than a quarter of the members of their own party were so extreme that they couldn’t imagine finding common ground with them.)

On the other hand, almost half of those in the other party were seen as “misguided but worth trying to find common ground with.”

That might provide an opening for a presidential candidate who wanted to exploit not the differences between the parties – the typical template for campaigns – but rather a desire on both sides to focus on areas on which Americans agree.

Four in 10 Republicans and nearly half of Democrats said they would be “tempted” to vote for the opposing party’s nominee if he or she had the best shot at unifying the country. Nine in 10 said it’s important to them that the candidate they vote for “actively works toward unifying the country and making it less divisive.”

It’s not clear how powerful that impulse would be in the face of the other factors that help determine whom voters support, however. A majority of voters in each party was unwilling to rule out voting for their party’s nominee even if he or she were running a divisive campaign.

“I do think the sentiment is real to want a political system that doesn’t seem quite as divided,” said Sam Rosenfeld, a political scientist at Colgate University and author of The Polarizers: Postwar Architects of Our Partisan Era. “But the Republican candidate and the Democratic candidate, once they become the Republican candidate and the Democratic candidate, are by definition going to be framing the opposition in ways that cast them negatively.”

At the moment, only 6% of those surveyed said the current presidential campaign was “bringing out the best in Americans;” 43% said it was bringing out the worst. Half said it was doing both.

Who fosters a constructive national conversation?

The harsh tone and fierce partisanship of the political debate have contributed to a downbeat outlook on the nation’s future.

Those surveyed had a sunny view of their personal lives – 87% said those were headed in the right direction – and a positive view of their communities, seen as on the right track by 69%.

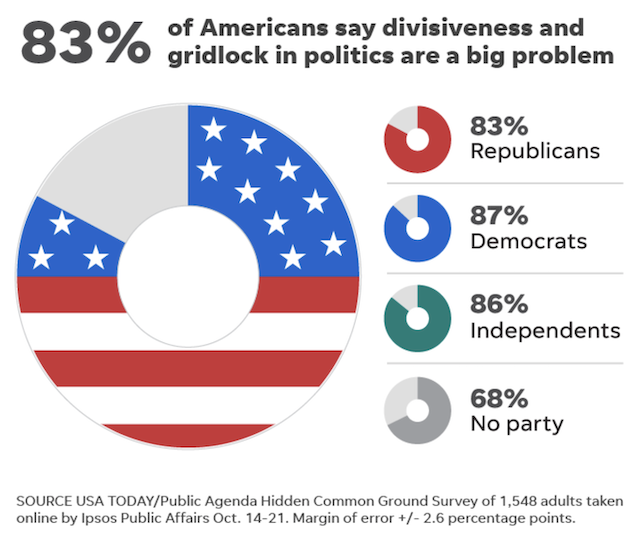

But only 28% said the country as a whole was headed in the right direction. Seventy percent said things have gotten off on the wrong track for the United States. An overwhelming 83% called divisiveness and gridlock “a big problem.”

Even so, nearly three in four said they saw more agreement among the American people than the news media and political leaders often portray. Only one in 10 said the problem was that Americans had too many fundamental disagreements and conflicting values. The bigger problem, according to more than four in 10, was that people didn’t know how to talk about conflicts in a constructive way.

Sixty-nine percent said Americans now deal with disagreements in a mostly destructive way. An overwhelming 74% said that situation had gotten worse over the past decade. Just 22% thought things would get better in next decade.

“People don’t know how to have a discussion without getting offended first,” said Kaveeta Haywood, 35, a Democrat who works in medical billing and participated in the New Rochelle focus group.

“We all have the same concerns,” said Walley Naylor, 66, a Republican from the focus group in Jackson. “We care about people. We all bleed red.”

But he said politicians benefit from exacerbating divisions. “I think they divide us with their rhetoric, because if we ever come together, we’ll kick their butts out, and they know that.”

The difficulty in having a constructive conversation about disagreements is driven from the top down, most said. By 76%-21%, they said leaders were setting an example that people were following, not that leaders were following the behavior that citizens already had. By 10-1, national political leaders are seen as promoting a mostly destructive discussion and debate.

Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter received nearly as negative a rating. Next were journalism and the news media, seen by about 4-1 as a mostly destructive influence – and as most likely to benefit from it, presumably by gaining higher ratings and readership.

“The saying used to be that sex sells; now it’s just negativity sells,” said Merrico Holliday, 43, an independent voter who joined the Jackson focus group. “Anything negative for social media, killing whatever. So that’s the only message that we’re given. That’s all the country is seeing. So I think we have a negative space right now.”

“Now it depends on what channel and what station you watch,” said Andino, the nurse in New Rochelle. “Wasn’t the media supposed to be neutral, to report on facts? Now it seems like the media is about their agenda, what they’re for. It’s political now.”

In all, 78% said national political leaders promoted a mostly destructive public debate; 74% said that about social media; 59% about journalism and the news media.

Among eight groups, not one was seen by a majority of those polled as promoting a mostly constructive public debate. Only two groups were viewed as more of a constructive influence than a destructive one: religious leaders and “ordinary people.” Ordinary people were also seen as the group with the most to lose from partisan disagreements and divisiveness.

But the ordinary people called in the survey expressed doubts about their own ability to constructively engage with people with whom they disagree. Republicans estimated that 52% of Democrats were “unapproachable.” Democrats said the same about 65% of Republicans.

“I think diversity is the key to democracy, (but) there’s a problem with people respecting other people’s opinions,” said William “Levi” Ingram, 60, a Republican retiree who participated in the focus group in Cincinnati.

Tacora Mizell, 34, a lab messenger and a Democrat, made a similar point in the New Rochelle group. “Certain people are ready to just argue instead of listening first to everyone’s opinions, then talking out their differences,” she said. “People just don’t know how to have discussions anymore.”

To be sure, there were ways they said they had tried to reach across the political divide. Eight in 10 said they have had a “constructive conversation” with someone whose political views differ from theirs. Most said they sometimes watched news from an outlet with different political views than their own. Three of four said they had “called people out” when they were rude, disrespectful or destructive. Nearly half said they had considered changing the way they behaved on social media.

But almost a third of Republicans and a quarter of Democrats said they had no good way of understanding the views of those in the other party.

Can we talk? How, exactly?

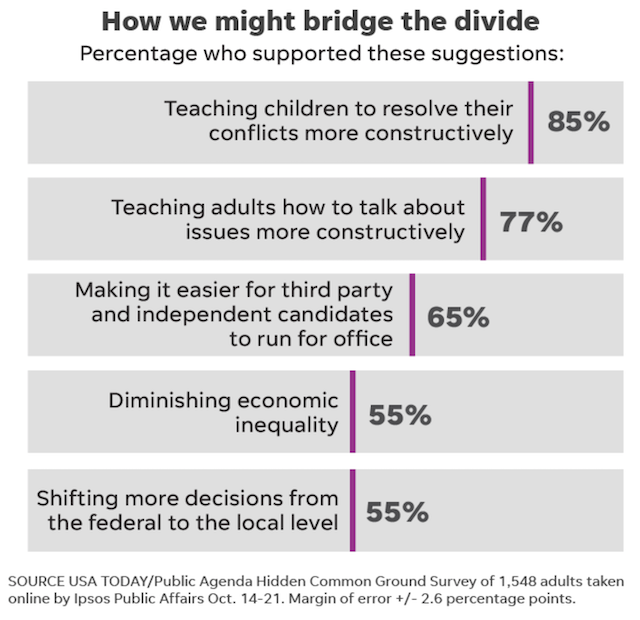

There was broad support for some proposals aimed at fostering a more civil national debate. Eighty-five percent endorsed teaching children to resolve their conflicts more constructively; almost as many supported doing the same for adults. Two-thirds backed making it easier for third-party candidates to run for office so voters had more choices.

A 55% majority liked the idea of shifting more decisions from the federal to the local level, where politics were seen as less partisan. That was more popular with Republicans, the party that has often backed returning power to the states. An equal 55% overall endorsed the idea of diminishing economic inequality. That was much more popular among Democrats, the party that more often talks about the need to address inequality.

There was support for more controversial proposals as well.

Half of those surveyed supported “stronger government regulation of news organizations to stop misinformation,” a move that seemed likely to conflict with the Constitution’s protections for a free press. More than a third endorsed stronger government regulation of social media “to make it less negative,” which might also collide with the First Amendment protections for free speech.

Nearly a third of those surveyed said the nation’s divisive public debate was having a personal impact on their lives.

About half of those respondents said they had been prompted to pay more attention to political news and commentary; nearly as many said they had decided to avoid it. Forty percent of them said they experienced depression, anxiety or sadness. More than a third had serious fights with friends or family members.

“Why should I get involved?” asked Joseph Burks, 59, a Democrat who works as an information technology administrator in Jackson. “What am I getting out of it? All I’m going to do is get upset. My blood pressure goes up.”

Dominique Carodine, 25, a counselor at Jackson State University, was more optimistic. “If both parties work together,” the Democrat said, “maybe they can focus on the everyday problems and stop saying ‘I believe this’ and ‘I believe that’ and just get to the problem, make solutions and keep going.”

RELATED: Figuring out how to talk to the other side is good start

The Hidden Common Ground project is supported by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, the Charles Koch Foundation, and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. The Kettering Foundation serves as a research partner to the Hidden Common Ground initiative.

Written by Susan Page for USA Today ~ December 5, 2019