A section of the reinforced U.S.-Mexico border fence in the Otay Mesa area, San Diego County, is seen from Tijuana in Mexico. President Trump says he may declare a national emergency to bypass Congress and build a border wall. ~ Guillermo Arias/AFP/Getty Images

President Trump declared over the weekend that he and his advisers were “strongly” considering a presidential declaration of a national emergency to bypass Congress and build a border wall.

“We’re looking at a national emergency,” Trump told reporters on Sunday, “because we have a national emergency.”

And yet on Tuesday evening, in his first nationally broadcast Oval Office address, Trump made no mention of it in a speech focused on border security.

That omission suggests three possibilities:

* The president has backed off from resorting to a national emergency decree to break the impasse over border wall funding.

* He is simply using the threat of a national emergency measure to pressure Congress to appropriate money for a wall.

* He fully intends to declare a national emergency along the Southern border if Congress does not fund a wall.

Back in the Oval Office on Wednesday, Trump assured reporters that a national emergency declaration remains an option. “I think we might work a deal and if we don’t, I may go that route,” Trump declared. “I have the absolute right to do a national emergency if I want.”

Trump said he would decide on doing so “if I can’t make a deal with people that are unreasonable.”

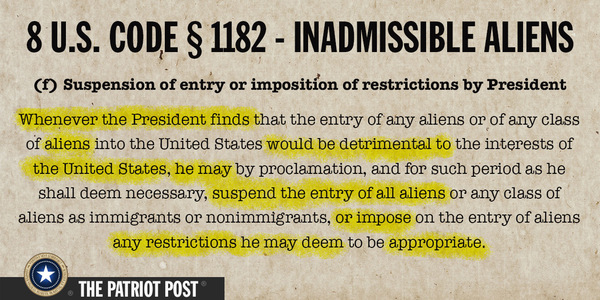

The president is correct

Some scholars of presidential emergency powers say there is next to nothing, at least procedurally, that Capitol Hill could do to stop Trump from exercising what lawmakers of all stripes agree is his right to declare a national emergency.

“Congress chose not to put any substantial — or really any — barriers on the president’s ability to declare a national emergency,” says Elizabeth Goitein, co-director of the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty and National Security Program.

“So if he can really just sign his name to a piece of paper, whether it is a real emergency or not,” she adds, “that creates a state of emergency that gives him access to these special powers that are contained in more than 100 different provisions of law that Congress has passed over the years.”

Trump has already invoked national emergency powers on three occasions, adding to the 28 earlier national emergency measures that remain in effect.

Almost all of them, including those signed by Trump, were invoked to freeze foreign nationals’ assets in the U.S. The longest-standing decree dates to November 1979, when President Jimmy Carter froze Iran’s U.S.-held assets.

Goitein’s Brennan Center has compiled a list of 136 statutory powers that Congress grants the occupant of the Oval Office on an emergency basis.

“Emergency powers have a place in a democracy,” says Goitein. “The concern is that in an emergency — and a true emergency, which is unforeseen and unforeseeable — the laws that are on the books might not be sufficient to deal with the emergency. It’s this idea that extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures.”

The problem, she adds, is that “democracy also has a place in emergency powers, and that’s where I feel like our current system isn’t serving us very well.”

Another expert on national emergency powers agrees.

“I think part of the problem here is that history messed with Congress’ original plan,” says Stephen Vladeck, who teaches at the University of Texas, Austin School of Law.

An effort to check presidential power

Congress had tried to remedy its lack of control over emergency powers in the mid-1970s, in a Washington rocked by the Watergate scandal.

At the time, once a national emergency had been declared, there were neither time limits for its duration nor requirements for reporting to Congress.

Congress’ reform effort was the National Emergencies Act of 1976.

It requires not only that the president formally declare a national emergency but also that he or she cite the specific statutory authority the president sought to use. An emergency declaration would lapse after one year unless formally renewed by the president.

There is also a means for lawmakers to do away with a national emergency decree.

“The way that Congress set it up,” says Vladeck, “was that Congress could basically terminate any national emergency the president declared through a concurrent resolution — simply through majority votes of both houses, without the president’s approval.”

That veto-free arrangement, though, did not pass constitutional muster when it went before the Supreme Court in 1983.

Congress’ response was to revise the National Emergencies Act so that the termination of an emergency decree required a joint resolution signed by the president. If the president vetoes such a measure, a two-thirds majority vote in each chamber would be needed to override.

That fix effectively set the political bar considerably higher for reining in presidential national emergency declarations — that is, should Congress ever try to do that.

“Congress has never voted once in the last 40 years — since the National Emergencies Act has been in effect — to terminate a state of emergency,” says Goitein. “At no point either before the court’s decision or after has Congress ever attempted to exercise this check.”

That may be, at least in part, because lawmakers trusted the National Emergencies Act was being invoked in good faith. “The assumption is that presidents are going to be relatively responsible in using those authorities and resources,” says UT’s Vladeck, “and are not going to just create some kind of pretext to allow them to go through a back door when Congress is denying them the front door.”

Two Traitors

Building a wall Congress won’t fund

Should Trump decide to circumvent Congress by declaring a national emergency to build a border wall, he would very likely rely on a statute that lets him reprogram unobligated funds that Congress has appropriated for military construction projects.

“It’s probably about $20 billion funding that the military has available right now in military construction and family housing accounts that has not yet been obligated,” says Todd Harrison, who directs defense budget analysis at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“So if President Trump were to use this money for building a wall,” Harrison says, “I suppose that would mean taking away money for other military construction projects.”

The prospect of Trump’s confiscating money designated for other projects has some prominent congressional Republicans worried, including Rep. Mac Thornberry of Texas. “I do not think it’s a good idea,” the ranking Republican on the House Armed Services Committee told MSNBC. “There are real needs today with barracks, and maintenance facilities and all sorts of military construction projects that are important for national security.”

Some predict a move by Trump to invoke a national emergency would get mired in litigation. “I think the president would be wide open to a court challenge saying, ‘Where’s the emergency?’ ” the House Armed Services Committee’s Democratic chairman, Adam Smith, declared on ABC.

Others aren’t so sure.

“Congress didn’t define what is and what is not a national emergency,” says Vladeck, “so it’s hard to imagine what criteria a federal court could use in trying to decide whether a national emergency was properly declared or not.”

If there were to be a court challenge, CSIS’s Harrison says, it is not likely to be over Trump’s invocation of the National Emergencies Act. A more plausible challenge, he says, would be over whether the wall Trump wants the military to build is aligned with a statute that stipulates any reprogramming of military funds must be “to undertake military construction projects.”

If there were to be a court challenge, CSIS’s Harrison says, it is not likely to be over Trump’s invocation of the National Emergencies Act. A more plausible challenge, he says, would be over whether the wall Trump wants the military to build is aligned with a statute that stipulates any reprogramming of military funds must be “to undertake military construction projects.”

“Border security is the responsibility of the Department of Homeland Security, not the Department of Defense,” says Harrison. “So I think it is not clear at all that the declaration of a national emergency here would actually allow the administration to use military funding for a nonmilitary purpose.”

Ultimately, Harrison says, it may be the landowners and local officials affected by the wall’s construction who would have legal standing to fight it in court.

Written by David Weina for National Public Radio ~ January 9, 2019