First light was almost upon us. I peered around the left edge of the ammo box. What I saw told me that there would be no more pawing around through the supplies dropped by the choppers in the dead of night. Through the misty rain, and what was left of the gently blowing night, I could see a slightly darker wave moving out of the jungle towards us. I also knew that we were all as good as dead if we stayed in our current position. It was either time to attempt to run back to the company lines under what covering fire the M-60s, grenades, and the Ontos could provide us or get back inside the hole and, with air hopefully on the way, wait the attack out and pray our hole wasn’t found. Three options, with not one of them being without high mortal risk.

First light was almost upon us. I peered around the left edge of the ammo box. What I saw told me that there would be no more pawing around through the supplies dropped by the choppers in the dead of night. Through the misty rain, and what was left of the gently blowing night, I could see a slightly darker wave moving out of the jungle towards us. I also knew that we were all as good as dead if we stayed in our current position. It was either time to attempt to run back to the company lines under what covering fire the M-60s, grenades, and the Ontos could provide us or get back inside the hole and, with air hopefully on the way, wait the attack out and pray our hole wasn’t found. Three options, with not one of them being without high mortal risk.

My near constant conclusion to evaluating combat solutions whispered out of my tight grimacing lips.

“We can’t go ahead, we can’t go back and we can’t stay where we are.”

The same situation, with all different terrain and other variables, ever-changing but never-changing to come together and arrive at the same three solution conclusion.

“We can always attack, Junior” the Gunny whispered into my ear, obviously having overheard my depressive whispered admission.

“What are you talking about?” I asked, surprised.

“Let’s get back in the hole and make-up one of your plans,” he replied, then began to slither toward where the hole was located.

Nguyen followed him and Fusner was about to when I grabbed his ankle.

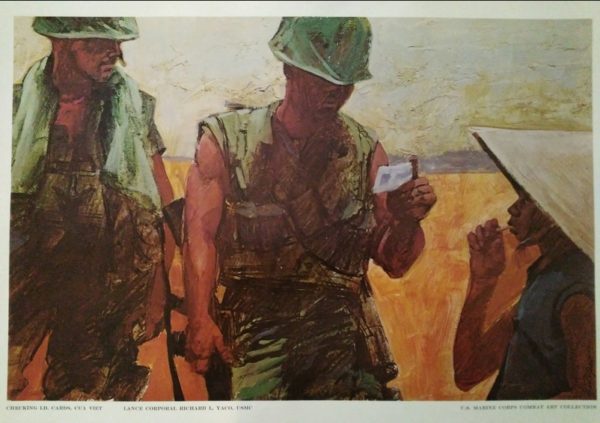

“Give me the AN-323. We have to have Cowboy or what’s coming across the flats will be the end of us by full dawn.”

“Talked to him, sir. He’s coming at first light,” Fusner got out, shaking his ankle to loosen my grip. “First light he’ll be here but he can’t come with the others because of the support they have to give Lima and Kilo.”

Fusner succeeded in getting loose from my weakened grasp and was gone ahead of me into the night. I crawled to catch up, well remembering my inability to find the hole on my own in full dark. It still wasn’t light enough to see well yet, and the mist was thickening into regular monsoon rain. The mist was actually harder to see through, but that wasn’t going to make much difference to the attacking force coming out from the jungle unless Cowboy could rain Skyraider hell down upon them.

The Gunny’s comment reverberated through my mind, as I crawled.

“Attack what, or who, or whom,” I muttered to myself, crawling along in the shallow path through the cloying mud left by the three before me.

The hole was there, but I only knew I had arrived by going right over the lip and dropping inside.

Fusner grunted as I piled headfirst into him. I slipped by him to land in the collected muddy water at the bottom of the hole.

“The plan,” the Gunny said across the total darkness.

I worked myself up out of the water to finally stand with both feet spread against the upwelling sides of the hole.

“Shouldn’t we be looking out there to see where the hell the NVA are?” I countered, wondering what kind of plan he wanted me to think up.

A plan that could have no foundation in reality that I could think of.

“Lima’s coming in from the south and they’re going to take it right in the side from Hill 975,” the Gunny said, speaking flatly and analytically. “Air is headed there to cover their move, little good that will do them. Kilo is headed across the eastern top edge of the highland again, to drop down the switchback parapet both our companies came down last week. Air is being diverted to cover their move too. That’s why only Cowboy is coming and he probably had to argue like hell to do that. Not like we haven’t over-used air a bit ourselves lately.”

“Lima’s coming in from the south and they’re going to take it right in the side from Hill 975,” the Gunny said, speaking flatly and analytically. “Air is headed there to cover their move, little good that will do them. Kilo is headed across the eastern top edge of the highland again, to drop down the switchback parapet both our companies came down last week. Air is being diverted to cover their move too. That’s why only Cowboy is coming and he probably had to argue like hell to do that. Not like we haven’t over-used air a bit ourselves lately.”

I listened carefully to every word the Gunny said. It was the single longest speech I’d ever heard him give, and by far the most complex tactically. Every word he said was dead on and I knew it. It was his conclusion, spoken earlier up above that had, and still, haunted me. Attack who, when and how?

“Okay, you’ve got all the data, Junior,” he finished. “What do you have for us?”

I didn’t have anything, and I knew we were about to lose whatever time we had to prepare for an advancing enemy. For some reason, the Gunny wasn’t worried about the attacking force we’d been able to barely observe moving across the flats toward us. Was the Gunny gambling that heavily on Cowboy’s arrival to nail them, or the remaining fire of the Ontos to deter them? It didn’t make sense since we were not hot on the radio talking back and forth to Zippo and the Ontos crew.

“It’s a feint,” the Gunny finally said, when the answer to his question was met with my complete silence.

“Feint?” I asked, dumbly.

“They aren’t really coming,” the Gunny replied. “I’ve seen this before. The old attack at dawn thing. They aren’t coming because they know air support will be here, and the Ontos will be able to see them before they can get onto the mud flat close to us.

“Why the feint, though?” I asked, still not even partially understanding.

“They’re going after Kilo but they don’t want us to know,” he went on. “They want us to cower here waiting for relief. Hill 975 forces are going to take Lima apart, the NVA regiment in the bush here is going to make mincemeat of Kilo, and then they’ll both take their sweet time in mopping us up in a pincer movement when they’re done with Lima and Kilo.”

My mind suddenly exploded with white light. I got it. I got it all. I thought for a few seconds to get everything he’d told me together.

“The plan is to roll the Ontos to us here, and then move the company south in three prongs,” I said. “One of our platoons along the lower ledge of the cliff, one along the side of the Bong Song and the last two behind and supporting the Ontos in its charge. We pick up the remaining supplies in the light with those two center platoons. Our machine guns can be concentrated at the very front edges of our moving forces, firing enfilade flanking fire from the outer prongs while the center gunners use ground fire to cover the Ontos as it moves forward into the jungle and through it while blasting away with flechettes and high explosives. Screw Lima and 975 until we’re done crushing this force between us and Kilo.”

“The plan is to roll the Ontos to us here, and then move the company south in three prongs,” I said. “One of our platoons along the lower ledge of the cliff, one along the side of the Bong Song and the last two behind and supporting the Ontos in its charge. We pick up the remaining supplies in the light with those two center platoons. Our machine guns can be concentrated at the very front edges of our moving forces, firing enfilade flanking fire from the outer prongs while the center gunners use ground fire to cover the Ontos as it moves forward into the jungle and through it while blasting away with flechettes and high explosives. Screw Lima and 975 until we’re done crushing this force between us and Kilo.”

“Fusner, get Kilo up on the net and fill them in,” I continued. “Then call back to the Ontos and the company. Get Sugar Daddy and Jurgens. We move on command at dawn just like the NVA was trying to convince us they were going to do. The Ontos makes all the difference, and finding the additional 106 ammo dumped out on the mud flats here becomes vitally important. The Skyraider is there for punch through power and psychology.”

I got out of my pack, pushed it to Fusner, and then climbed my way to the top edge of the hole, standing on the platform the Gunny had fashioned. I could see the jungle as a rotten gray line, thick with moisture and mixed with the slanted rain now falling. Dawn was only minutes away. There was no enemy, as the Gunny had predicted. They’d come out under cover of darkness, absorbing our sniper fire, as a price of doing business, then faded back once they thought they’d put the fear of God into us. I stared toward the jungle and then turned to peer back up where our lines were. The Ontos was still invisible against the dark backdrop of the cliff face, but I knew it was there. I glanced once more down at the jungle area that was now totally quiet except for the thrum of the river’s passing and its ever-changing currents and eddies.

“They thought we’d be afraid,” I said out loud, to no one but the sodden rainy night around me. “They think we’re not a bunch of totally whacked out Marines with nothing to lose. Well hell, we’re afraid all right, but we’re about to become afraid for them and not of them.”

Saying the words made my back stiffen and my shoulders lift a bit. There was no real hope in the valley, but there was some satisfaction to be found here and there, and I just knew this was going to be one of those times where some satisfaction might be found. I canted my head down, listening to Fusner putting the Gunny on the radio with Kilo.

“It’s almost light, Fusner,” I said, looking down at the top of his helmet. “Maybe it’s not too early for your crummy little Armed Forces radio. Turn it on. We’re not attacking in silence.”

“The name, sir?” he asked, without twisting up from his position in supporting the Gunny while he talked on the short-corded handset.

I waited, looking up again into the rain while trying to gather some of it with my tongue. My hands and the rest of my body were encased in the awful smelling mud. I realized my old leeches were still with me, as I’d had no time to strip and get rid of them. I smiled at that thought, waiting for God’s inspiration. Maybe the leeches in the mud were really there, after all, I thought. Maybe the leeches that had to be there simply recognized that I was already taken. I was already owned by their brethren, and I had only so much blood to be equally distributed around.

Fusner fiddled over his tiny transistor radio. I knew the music, if it came on, wouldn’t matter in our current situation. The mock attack was over and, in minutes, the machine guns, the Ontos and hopefully the Skyraider fire, would drown out all other sounds. The song came, and I struggled to listen to the words I didn’t really know. The song was from the Beatles and it was already halfway through when it played up to the top of the hole. There wasn’t enough light to see the Gunny’s face when he glanced up at me in irritation, but I imagined his expression, and his patient waiting for what was to come next, and for my inspiration. It came with the lyrics: “Penny Lane is in my ears and in my eyes, there beneath the blue suburban skies, I sit, and meanwhile back…” The song was called Penny Lane and the plan was named. I remembered the only lyrics I retained from hearing the song in college. Something about a nurse and poppies and those lyrics had back then, and right now, taken my mind to the famous WWI poem that had affected me.

“We are the dead,” I intoned to myself from the poem, “short days ago, we lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow…”

“Penny Lane,” I said down into the hole. “The plan is called ‘Penny Lane‘.”

There was no way I was going to call the plan Flanders Fields.

The Gunny surged upward a few minutes later.

“The kid’s radio’s a bad idea and I don’t understand the name of this new plan,” he said, moving to lay next to me, with half his body out of the hole to keep his place.

“Kilo’s gonna be saved for the third time, which is kind of ridiculous if you think about it,” he said. “Lima’s gonna pay the price but it’s not one we laid on them. And these NVA son-of-a-bitches plaguing us from the beginning are going to feel our bite, as long as they’ve moved that .50 to help them pick Kilo off the side of that wall like slow-moving flies, that is.”

“Attack,” I whispered. “Attack. Where in the hell did you come up with that idea?” I asked.

“It was your idea, Junior, but Penny Lane, my ass.” He slipped back into the hole.

I ducked down, although there was no incoming fire. I squatted on the small step, my back pressed into the muddy side of the hole, still too dark to see anything but ghostly shapes, and then only if they moved. The platoon moving along the cleft overhang of the canyon face would be in the same situation as Lima Company was going to be in, as they moved south past Hill 975. Fire from the jungle side would pin our platoon against the cliff, while Lima would be pinned against the raging unswimmable Bong Song. My platoon would have one distinct advantage, however, and that would be the fire pouring into the jungle from the riverside platoon, along with the Ontos plowing through the jungle and dispensing flechette rounds forward and to either side. The NVA would at first believe they were pinning Kilo to the cliff before they would only slowly come to understand that they were the ones surrounded on all sides. The only place they would have to go would be down into their tunnels. Resupply. The word came logically to me, as I thought about dislodging or destroying tunnel works. Satchel charges, large and many would be needed.

The shock waves from such underground blasts, as the charges were tossed into any openings that could be found, would penetrate up and down the tunnels, even sending terminal waves through solid ground.

“Fusner, get battalion on the line,” I ordered. “I want another resupply to our rear, as we attack into the jungle. We need more flechette rounds for the Ontos and we need satchel charges for the tunnels.”

“They lost Marines on that last one, sir,” Fusner replied, instead of moving to get on the net and making the call.

“And, so?” I asked, surprised he hadn’t simply made the call.

“They won’t come into a hot LZ where they’ve taken casualties,” the Gunny replied, “and you already know that. Besides, the 106 ammo will arrive too late and the satchel charges can wait until we’ve secured the surface to set them if we secure the surface.”

The Gunny was right again, I knew, although I was beyond the point where such missing of tactical elements embarrassed me. I had been reduced to needing all the help I could get, and what pride I’d had when flying into the country was all but crushed into non-existence. We were going to use a frontal attack on a most capable and equipped enemy. That knowledge was the only thing I could use in my mind to scrape up any sense of my old Marine Corps pride. I was, once again, hiding in a hole, but I was coming out and I was coming out fighting, and soon.

“We’ll let the choppers know the surrounding area is secure as soon as we get into the jungle,” the Gunny continued, “and it won’t be, but what the hell, we can always call the Army if the Corps pilots won’t come.”

It was strange to think about the amazing and conflicting belief systems that floated down into the A Shau field of combat and through the rear area surrounding it. The Army thought of the Marine Corps as the ultimate fighting force that it was not. The Marine Corps fought, but when the going got tough defaulted to the Army for help for what the Corps rear area couldn’t or wouldn’t provide.

The Marine Corps delivered in a broken sort of tattered leadership way but delivered. The Army delivered in the following role, but also effectively delivered.

“Besides,” the Gunny said, in a lower voice, “the next resupply will also drop another contingent of FNG officers to relieve you, Junior. You are not the best-liked officer ever to land down in this valley.”

“The men like him though, Gunny,” Fusner said in the darkness.

“The men don’t like him,” the Gunny shot back, anger in his tone. “The Marines didn’t give a shit about anything when he dropped in. Now they want to go home. Figure it out.”

“He gave us hope,” Fusner continued, in a dogged low tone.

“He made it so nobody wants to be around him,” the Gunny shot back. “They want to go home to get away from him.”

“That’s kind of like hope,” Fusner replied, his sentence more of a question than a statement.

“They’re ready,” the Gunny said, changing the subject. “Where’s that extra grenade you had? The company moves out in three columns on that signal. Sugar Daddy’s coming high diddle-diddle right up the middle to follow and support the Ontos. The sniper team will do rearguard because I want them ready, with their weapons aimed at the last location of the fifty-caliber, the only flea I see in this plan of yours. If that thing opens up then they have to shoot the gunners or our goose is cooked, because we’ll be fully committed.”

I moved down from the step and began rummaging around for my pack, staying as far up from the cloying mud as I could. Fusner pushed it into my chest, as I floundered about. The M-33 was where I’d left it. I pulled it out, handling it gingerly. The 33 had a questionable reputation. The M-26 that had preceded it had been the old faithful of grenades, following the infamous pineapple grenade used in WWII and Korea. The 33 had a temper all of its own. Some said the pin was too easy to dislodge, others said that the timing fuse, supposedly measured to be five seconds precisely at the factory, was not as advertised. I didn’t really care. I would pull the pin, or the Gunny would, toss it ten meters away, or so, and then let the thing go off. I eased myself back into the alcove gouged out of the side of the hole, held the grenade tightly to my chest with both hands and waited.

Why was the Gunny sticking to the phony story that the plan to attack was my idea? I had no clue. Why had he chastised Fusner about what my Marines either thought or didn’t think about me in such a negative and emotional way? Once more, I had no idea. That the Marines might want to get out of the A Shau, only to escape me, didn’t seem plausible from everything I’d experienced. I knew that many of them carried superstition packets around their necks with some of my stuff in them.

Superstition ran rampant, like gossip, in a field unit, and maybe in the rear areas too. It was only natural for the men to think my amazing survival from time to time, as opposed to the previous officers who’d come and gone so quickly, might have something to do with magic. That many of those officers had died at my Marines’ own hands seemed not to count. Fusner thought I’d somehow given the men some sort of hope of survival, and it seemed that the Gunny was ready to unwillingly go along with that in conducting the current operation while, at the same time, indicating that the men were more interested in getting away from me than anything else.

“Ready on the right,” the Gunny whispered.

I prepared myself to climb up, pull the pin on the M-33 and then toss it, but first I strapped myself into my pack. There would be no coming back to the hole once we began the attack. Just as I turned to climb up to the lip of the hole, the AN-323 radio kicked to life. There was no speaker for that radio but the small noise the tiny headset speaker made was very audible in the near silence and dead air down inside the hole.

“Cowboy rolling on in,” a small tinny voice said. “You got your ears up and ready for that Flash?”

I climbed back down and reached for the headset, pressing my right ear into the small speaker, as I did not want to remove my helmet and risk dropping it into the muddy water below. I squeezed the grenade in my left hand uncomfortably but wasn’t about to part with it.

“Flash standing by,” I said, pressing on the transmit button and hoping our position deep inside the hole wouldn’t block the signal. It didn’t.

“I’ll be five by five when you start your run,” Cowboy said. “I’m a lone soldier up here, orbiting and waiting out the dark, and for your signal. “I’ll make a hole for your Ontos right down the center. I know the area well. I’m loaded for bear with maximum ordnance for the effort. Is it Penny for Your Thoughts or Penny Lane?”

“Penny Lane,” I said back, astounded by how quickly and effectively something as seemingly slight and unimportant as a plan name could spread and be totally accepted. “There’s enough light to launch, Cowboy, and the line of departure will be about ten meters south of the flash from the grenade I’m about to toss from our hole.”

“That’s rich,” Cowboy laughed. “A flash from Flash. I’ll start my roll in from eight thousand and hopefully, singe the hair of the guys riding that Ontos into history and Valhalla. Out.”

I pushed the headset back at Fusner, now barely visible in the pre-dawn light. I climbed back up on the step and pulled the pin on the grenade with a bit of difficulty because of the slipperiness of the mud on my hands. The M-33 felt perfect in my right hand, the spoon pressed hard against the pool ball sized round surface of the body of the device. I stretched my arm back, like my Dad had taught me to do when trying to throw a football as far as I could, and then heaved the grenade back toward our own line so the flash would radiate out from the top of the mud in front of every Marine present.

I pushed the headset back at Fusner, now barely visible in the pre-dawn light. I climbed back up on the step and pulled the pin on the grenade with a bit of difficulty because of the slipperiness of the mud on my hands. The M-33 felt perfect in my right hand, the spoon pressed hard against the pool ball sized round surface of the body of the device. I stretched my arm back, like my Dad had taught me to do when trying to throw a football as far as I could, and then heaved the grenade back toward our own line so the flash would radiate out from the top of the mud in front of every Marine present.

I never saw the flash, as I’d dived back inside the hole when the grenade was still in the air. I heard the small ‘crump’ of its explosion seconds later. I unsnapped the holster flap covering the butt of Tex’s .45 and got ready to climb out of the hole. I was as ready for open combat as I would ever be.

“Wait one,” the Gunny cautioned. “Wait until we can hear the Ontos and then gauge its position. Everyone on our side is aiming out front of that thing and the last place we want to be is there.”

I tried to settle back, but my pack stuck out too far to allow me to force myself back into the crease in the corner of the hole. I stood, with feet spread to stay above the inches of muddy water in the bottom, like the Gunny, Fusner, and Nguyen. I had run through the enemy before, as I had run from him, but I had never charged forward in attack.

Getting ready mentally for the effort was not what I thought it might be. I wasn’t nearly as afraid as I thought I should be. I was instead hoping. I was hoping that I would measure up as a Marine in combat and I was hoping my company would be able to do the same. For only the second time since being in Vietnam, in combat and down in the A Shau Valley, I was feeling like I thought a Marine was supposed to feel.

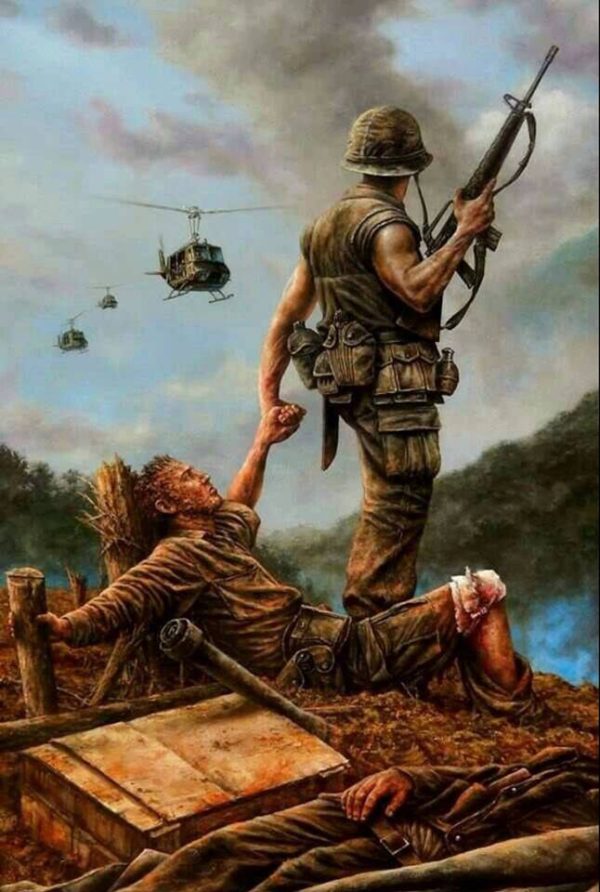

I felt the Ontos vibrate the walls of our hole and suddenly wanted to be out on the mudflat, no matter the risk. My fear of being buried alive in the mud was greater than that of being shot, even if that was to be by my own Marines. I vaulted up the step and over the lip of the hole. I felt the others following me. The Ontos was idling right in front of me, it’s left tread no more than a few feet from the hole. Zippo sat atop and just behind the layered armor of the thing, his teeth exposed by a huge grin, about the only thing fully visible about him. I heard Cowboy coming in the background but knew the shape of the valley was also radiating sound well ahead of the fierce lumbering beast of the air. But he was there and coming.

I ran to the back of the Ontos, the Gunny pulling up to my side and Fusner not far behind. Nguyen popped up from under the rear of the machine, having taken the easiest path by sliding right under the hull of the thing.

“Ready,” the Gunny yelled into the open rear doors of the Ontos. “Are you going inside?” he shouted in my ear with his hands cupped.

“Ready,” the Gunny yelled into the open rear doors of the Ontos. “Are you going inside?” he shouted in my ear with his hands cupped.

I looked up at the open doors of the beast. There was room. I made a quick decision, following my new feeling of being an actual leader of Marines.

“No, I’m staying with the men,” I yelled back.

“Then get two hundred meters back. When the 106s start to fire you have to be either under the thing, inside it, or a hell of a long way from the back-blast.”

I turned to look up the mild incline to where the company had been set in. Everyone was on the move, and most had M-60 machine guns carried with ammo belts held by assistant fire team leaders just aside or behind them. Sugar Daddy’s platoon I knew, because they were so difficult to make out in the bad light. The Marines of one platoon moved against the face of the cliff. I turned once more to watch Jurgen’s platoon heading down to the raging water’s edge.

“Move out,” the Gunny yelled, as I achieved a position far enough away from the Ontos, with Fusner and Nguyen by my sides.

The Gunny had stayed with the Ontos, squeezing into through the doors. I wondered if he’d done that to build me up more or whether he’d done it for security. The last part of that thought made me smile grimly. The Gunny didn’t do much at all for his own security.

He’d done it to make me feel like a Marine Officer and it was working.

Written by author James Strauss for his Book and Blog ~ Third Ten Days

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml