Never has the stock market soared higher nor the supply of affordable books been cheaper. Lucky or cursed, let us examine the latter about which T.S. Eliot asks a great question but falls short in his reply.

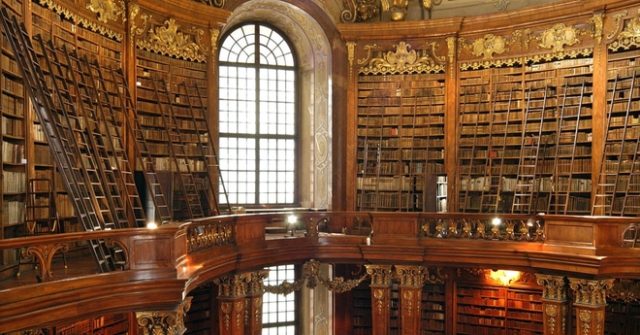

I confess, I adore them. I thrill to their touch; my heart is aroused by their scent. If old and forgotten, leather-bound and time-worn, books whisper all the more seductively; offering to share ancient secrets unknown to other living souls. They conspire to delight me; and I could no more write in one than scar the face of a mortal lover. If asked to choose between books and oxygen, I would select the latter only to enjoy a few more lingering moments with the former. ~ T.S. Eliot

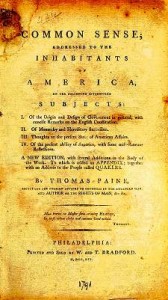

Books were once expensive. In Samuel Johnson’s day, just one cost as much as a labourer’s entire weekly pay of nine shillings; while the modern equivalent, $600, buys about seventy-five non-fiction paperbacks averaging seven dollars each. Yet, not only because there were fewer pastimes did people sacrifice to buy books: There was a thirst. Throughout 1776, one in five colonial families bought Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which cost them as much as a mid-range laptop today. Presumably, each copy was read by every adult in the family, as well as by friends and neighbors.

Books were once expensive. In Samuel Johnson’s day, just one cost as much as a labourer’s entire weekly pay of nine shillings; while the modern equivalent, $600, buys about seventy-five non-fiction paperbacks averaging seven dollars each. Yet, not only because there were fewer pastimes did people sacrifice to buy books: There was a thirst. Throughout 1776, one in five colonial families bought Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which cost them as much as a mid-range laptop today. Presumably, each copy was read by every adult in the family, as well as by friends and neighbors.

Paine’s book sales, adjusted for today’s larger population, add up to sixty million copies. What he sold, in only one year, equalled what took eight years for Dan Brown’s comparatively cheaper The Da Vinci Code. But Paine’s publishing success cannot be replicated: Experts believe that only thirteen per cent of modern Americans can read with sufficient fluency to understand Paine’s book. If today’s dire literacy estimates are correct—and each copy of Paine’s tome passed through only four pairs of hands—the percentage of highly literate colonists must have been about seven times larger than that of us.

Of course, literacy statistics are often unreliable, fraught with error or even fraud. This author has seen UNESCO endanger millions of children’s lives intentionally, in order to publish fraudulently self-flattering statistics on vaccination; so their buoyant literacy claim of ninety-three percent of Americans, and eighty-three per cent worldwide, may be equally spurious. Many poor countries boost their literacy figures by lowering standards; sometimes requiring only that the allegedly literate can simply sign his name. There are incentives for fibbing either way. Literacy charities seek government funds, now claiming that ten per cent of mankind lacks sufficient reading skills, while the regime of UN grandees may wish to declare the problem mostly solved, and leave the aftermath for their unlucky successors. Yet competing assessments, and even anecdotes, shed some light.

The US Department of Education states that eighty-five per cent of juvenile delinquents, and seventy per cent of all prison inmates, are functionally illiterate, as are fourteen per cent of all Americans (thirty-two million). Others report that the US is the only developed nation (OECD) in which each generation is less literate than its predecessor. One in five Britons is functionally illiterate.

The anecdotes are even more convincing. A US civics study found that more American teenagers were able to name The Three Stooges than recall the three branches of the federal government. British men’s magazines have cut back their stories from 450 words to 150, because their readers can tolerate no more. So, for any would-be Tom Paine, the bad news is credible in terms of illiteracy; but that is not all. Beyond cash and ability, reading a serious book requires time and will.

In the fourteenth century, some eighty per cent of Britons could not spell their names, but they had spare time aplenty: The average Northern European peasant worked only 150 days a year, leaving 215 days off for festivals, lounging between planting and harvest, etc. But few had access to hand-written books. By the fifteenth century’s Age of Gutenberg, thirty per cent were literate: From 1471-1500, The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas à Kempis, soared through ninety-nine editions, while works by Erasmus and Luther did almost as well a generation later. Throughout the Georgian Age, English literacy was forty-five to sixty-three per cent, rising to as high as eighty-five per cent in Scotland. Like their American cousins, they read voraciously, buying costly books or paying low charges to private lending-libraries.

Through the whole nineteenth century and its Industrial Revolution, Britons averaged a ninety-hour work week, toiling almost year-round. By 1860, it fell to sixty-six hours a week, and dropped by six more hours in 1890. Despite long hours, they kept reading because artificial lighting grew cheaper, and there was little else to do for relaxation. Bible-reading societies, the demands of industry, schooling for poor children, and affordable, serialised novels kept more people reading.

Now Europeans are almost back to working medieval hours: Counting holidays, weekends, and vacations, the British take off four months a year and Spaniards five. Only the US averages a miserly eight vacation days a year. Even so, the average American enjoys nearly five hours of leisure per working day; spending almost three hours watching television, forty minutes socializing, and nineteen minutes reading — not only books. It is complicated: Just more than half of nine-year-olds read every day, in 1984 and now; while the number of seventeen-year-olds fell by a third. Almost two-thirds over age seventy-five read daily, but primary school students and the retired cloak the grim reality by reading more than the others. Technology offers distractions unavailable to Thomas Jefferson; and there is no doubt that Americans choose to read far less, and less proficiently, than their colonial forebears.

Next, if you write a masterpiece, will anyone notice? In 1759, Britain published only one hundred new titles a year. So, if you set Sundays aside for bible-study, and you devoured a book every three days, a year saw you through every new book. Now, to digest each of the half-million new titles published annually in the US and UK, you must read almost fourteen-hundred books every day. Across North America alone, around ten-thousand history titles are published each year (twenty-seven per day), roughly the same for biography and double that for science; in only America, fifty-thousand novels (137 per day). To keep up in agriculture, you need only read four whole books a day. It is impossible. Long ago, perusing everything, including the Georgian Era’s contemporary drivel, demanded reading fewer than two books a week.

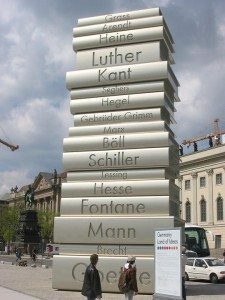

Now, our enormous stack of books has become our Tower of Babel, depriving us of common references. They still existed fifty years ago, when every Briton who mattered read two out of three national, daily newspapers, promoting a few select titles. The American intelligentsia had a small stack of monthly journals. Now there are, literally, 175 million blogs worldwide. Even if you find good books, your friends are led to different ones.

Now, our enormous stack of books has become our Tower of Babel, depriving us of common references. They still existed fifty years ago, when every Briton who mattered read two out of three national, daily newspapers, promoting a few select titles. The American intelligentsia had a small stack of monthly journals. Now there are, literally, 175 million blogs worldwide. Even if you find good books, your friends are led to different ones.

For bookmen it is hell. The old family-owned publishers were sold off to multinational conglomerates that watch quarterly profits, but do not care if they sell condoms instead. Faber & Faber’s big risk—publishing the little-known George Orwell’s first fiction that covered their other losses for two decades—would not be allowed today.

Great literary biographers, still alive and who once guaranteed twenty-thousand copies sold, can barely sell three thousand and earn no advances. Sharp marketing produces reams of populist tripe that often shows a loss, while promising authors no longer get even piddling advances that would have kept them freezing in a garret—now they cannot afford to even try. Belles-lettres is dead as a genre, after three centuries; and no publisher will take the chance. Even a predictably loss-making, ghost-written, celebrity autobiography looks safer when the parent multinational’s auditors come calling.

Panic-stricken publishers are swamped with manuscripts: Eighty per cent of Americans wish to become authors, and asking Google how to have a novel published gathers seventy-five million replies. The successful earn less than five-hundred dollars per novel on average, or lifetime sales of less than $3,000 for a non-fiction book. But each writer expects to be the next J.K. Rowling.

With no time in which to read the innumerable, abysmal manuscripts for every published book, editors hire others to slog through their inboxes–often premature spinsters from Oxbridge or the Seven Sisters, who prefer feminist or other girly fare that drives away male readers. Boys’ books are a dead file. Meanwhile, publishers are under ever-mounting pressure, from their plutocrat masters, to find an ever-more elusive best-seller, while the corporate risks plainly warn them to play safe and copy their competitors.

Now and then, a few diamonds emerge from the dung-heap. The Harry Potter series, Tolkien’s works, and C.S. Lewis’s Narnia tales sold between three-hundred million and four-hundred million. Word of mouth, and modern social-media, help to winnow wheat from chaff; while a few new publishers, of old-fashioned taste and quality, perform the equivalent of pouring champagne into Lake Erie. Overall, the technology that makes books cost less reduces the profits per book, and so hungry producers generate greater quantities, targeting ever-smaller niche markets. Falling literacy also contributes to falling sales per title. Longing to escape from the Slough of Despond, most novelists self-publish; fine for entrepreneurial authors such as Shakespeare, Defoe, or Dickens, but many were, or are, simply not salesmen.

It may be that a surfeit of would-be authors, successful authors, and inexpensive books, is a mixed blessing, while growing illiteracy and multinational mismanagement are definite curses and the internet is a quagmire. T. S. Eliot raises a pertinent question for the Information Age. In his 1934 play, “The Rock,” his chorus asks: “Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?” But Old Possum gets it wrong in “The Hollow Men,” asserting,

This is the way the world ends This is the way the world ends This is the way the world ends Not with a bang but a whimper.

No, it is worse. It ends with multitudes rejecting human company, and choosing to socialize for less than an hour a day; with thirty million Americans blogging furiously and the same precise number unable to read; with the latter glued to the idiot-box and eighty-seven per cent unable to fathom a serious book; while media-mad millions type manuscripts that will never be printed, despite 1.5 million titles a year in the US and the UK, published professionally or personally; leaving us few books in common about which to talk; and with too many, in daemonic fury, communicating chiefly to one’s self.

But why? Why do people, with less and less to say, need to talk more and more? Has there always been an innate, self-obsessed, human need to prattle, recently unleashed by technology and leisure? Was it pent-up before, like evils scratching to escape Pandora’s Box? I doubt it.

People who wrote letters to newspapers were formerly dismissed as eccentrics; and our grandparents said of celebrity, “Fools’ names and fools’ faces; Are often found in public places.” People once knew who they were and kept content, or needed approval from no more than family and a few friends. Now, quoth the Raven, “Nevermore,” and, to paraphrase the Zen master, “what is the sound of one hand blogging?”

Gresham’s Law—that bad money drives out good—describes the fate of modern writing and publishing. Yesteryear’s few essayists are replaced by many poor writers, by young PR-hacks, with dubious degrees in media, whose work is ghosted on behalf of politicians or media celebrities. Publishers hire them too, not as ghost-writers, but as unskilled commissioning editors and skilled corporate grease-balls. They hire them for what now matters: A tasteful, bookish youth would only kill herself and put up the insurance premiums. Even in bookish circles, I can no longer recall anyone discussing a writer’s style or repeating a well-turned phrase. I may as well long for someone to compliment a handsome bay or a well-made buggy.

Gresham’s Law—that bad money drives out good—describes the fate of modern writing and publishing. Yesteryear’s few essayists are replaced by many poor writers, by young PR-hacks, with dubious degrees in media, whose work is ghosted on behalf of politicians or media celebrities. Publishers hire them too, not as ghost-writers, but as unskilled commissioning editors and skilled corporate grease-balls. They hire them for what now matters: A tasteful, bookish youth would only kill herself and put up the insurance premiums. Even in bookish circles, I can no longer recall anyone discussing a writer’s style or repeating a well-turned phrase. I may as well long for someone to compliment a handsome bay or a well-made buggy.

Blame leisure as the enabler, or psychology as the perpetrator, or technology as the murder weapon; or the slain body of faith as collateral damage from the last failed hope for community and self-worth. Pick any one and you may not be wrong; choose them all and you may be right.

So, neither with a bang nor a whimper, the world ends with the remains of Western Civilization, now unlettered for many reasons, increasingly under-read, alone by choice, and still self-compelled to communicate.

Written by Stephen Masty and published by The Imaginative Conservative ~ March 2, 2015.

~ The Author ~

~ The Author ~

Stephen Masty (1954-2015) was a Senior Contributor to The Imaginative Conservative. He was a journalist, a development expert, and a speechwriter for three US presidents, British royalty and heads of government in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. He spent most of his adulthood working in South Asia including Afghanistan, and he was a writer, poet and artist in Kathmandu.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml