An aspiring ob-gyn’s views on abortion might determine what training she seeks out, which specialities she pursues, and where she chooses to live. In a post-Roe world, that self-sorting process would grow even more intense.

For a long time, Cara Buskmiller has known two things about herself: she wants to deliver babies, and she is called by her faith to a lifetime of virginity. Growing up in nineteen-nineties Dallas with six younger siblings, Buskmiller knew a little about pregnancy and birth, and was interested in medicine. But she truly decided on obstetrics in the seventh grade, after touring an ob-gyn’s office with her Girl Scout troop. She saw posters promoting contraception on every wall – something her parents, devout Catholics, had taught her was wrong – and she thought, Oh, my gosh, I have to become an OB to combat this!

For a long time, Cara Buskmiller has known two things about herself: she wants to deliver babies, and she is called by her faith to a lifetime of virginity. Growing up in nineteen-nineties Dallas with six younger siblings, Buskmiller knew a little about pregnancy and birth, and was interested in medicine. But she truly decided on obstetrics in the seventh grade, after touring an ob-gyn’s office with her Girl Scout troop. She saw posters promoting contraception on every wall – something her parents, devout Catholics, had taught her was wrong – and she thought, Oh, my gosh, I have to become an OB to combat this!

Her second vocation took longer to discern. She tried dating in college, carefully considering all the eligible Catholic men she knew, but no one felt like an obvious match. She flirted with the Catholic Church’s version of a sorority rush for nuns, visiting convents and chatting with sisters to see whether that should be her path. But it turned out that the answer was in her own family: her great aunt Marjorie, a former teacher, was a consecrated virgin, dedicated to chastity and obedience while also able to pursue an independent professional life. Today, Buskmiller is unfazed by questions about why a professed virgin would specialize in a field of medicine that’s all about sex. “Doesn’t God have a sense of humor?” she asked, chuckling.

But in 2010, as Buskmiller prepared to apply to medical school, she worried that admissions committees would be skeptical of her beliefs, and how her personal objections to abortion and birth control would affect her practice as an ob-gyn. What would program directors think of the volunteer stints she’d done at a crisis pregnancy center? And, when it came time for residency, would she be able to duck out of certain clinical rotations to avoid assisting with abortions?

Buskmiller got into medical school at Texas A. & M., and she went on to do her residency at St. Louis University, a Catholic school. But she felt that students like her needed more backup. So, during her second year as a resident, she launched a Web site called Conscience in Residency, a support network for doctors-in-training who have moral objections to abortion. The site’s tagline is “You’re not crazy, and you’re not alone.” Buskmiller maintains a crowdsourced spreadsheet where residency candidates note which institutions made them feel welcome – and which ones didn’t. An “abortion ‘mecca,’ ” someone commented about Oregon Health & Science University, in Portland: “Two faculty members stated directly in medical student lectures that they think anyone holding a conscientious objection to abortion should reconsider if it’s ethical to be an ob-gyn.” Another commenter wrote, of Southern Illinois University, in Springfield, that the program director “seemed very shocked when I asked about opting out of sterilizations.” Most of the residents, the commenter added, “are very involved in ‘abortion advocacy.’ ”

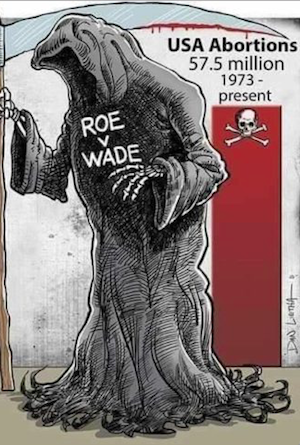

Even in an era when Roe v. Wade looks likely to be overturned, residents who describe themselves as pro-life are countercultural within their field. They believe that fetuses are human persons with moral status; when Buskmiller encounters a woman in even the earliest stages of pregnancy, she sees two patients, not one. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, or acog, on the other hand, firmly maintains that abortion is a form of health care and supports the right of a patient to terminate a pregnancy before fetal viability. Progressive physicians and students argue that abortion access is not just crucial for their patients’ health but for a more economically and racially just society. They believe that abortion can help keep families out of poverty and that it protects the lives of Black women, who, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are three times as likely as white women to die from pregnancy-related causes. Meanwhile, residency-program directors may hesitate when they encounter students who decline to participate in abortion training, which involves learning how to care for patients in emergencies as well as before and after the procedure. Even doctors who don’t perform abortions are likely to encounter patients who have had them. Knowing more about that experience makes them better practitioners, Jody Steinauer, an ob-gyn professor at the University of California, San Francisco (U.C.S.F.), said.

Still, there’s a surprising amount of subtle variation among how people in the medical community think about this issue. All students and young doctors have to sort out questions of how they want to practice medicine; aspiring ob-gyns’ views on abortion might determine what training they seek out, which specialities they pursue, and where they choose to live. In a post-Roe world, that self-sorting process would grow even more intense: in roughly half the country, abortion would be all but illegal, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive-rights think tank. Medical residents in those states would likely have to go elsewhere to learn about abortions, just as patients would have to travel to get the procedure. In the other half of the country, demand for abortions would almost certainly shoot up, putting pressure on physicians, hospitals, and clinics to serve patients from out of state. For all doctors and trainees, no matter their views, this geographic divide could pose dilemmas – even for anti-abortion students who would presumably welcome the reversal of Roe. Simple slogans and tidy categories are useful for politics but not for medicine. “Pro-life people do not understand why gynecologists talk about the need for abortion until they see a woman dying in front of their eyes because they’re pregnant,” Buskmiller said. “I think it’s possible to be pro-life, in spite of those situations. But we can’t have rose-colored glasses and think the situation is easy. It is not.”

Still, there’s a surprising amount of subtle variation among how people in the medical community think about this issue. All students and young doctors have to sort out questions of how they want to practice medicine; aspiring ob-gyns’ views on abortion might determine what training they seek out, which specialities they pursue, and where they choose to live. In a post-Roe world, that self-sorting process would grow even more intense: in roughly half the country, abortion would be all but illegal, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive-rights think tank. Medical residents in those states would likely have to go elsewhere to learn about abortions, just as patients would have to travel to get the procedure. In the other half of the country, demand for abortions would almost certainly shoot up, putting pressure on physicians, hospitals, and clinics to serve patients from out of state. For all doctors and trainees, no matter their views, this geographic divide could pose dilemmas – even for anti-abortion students who would presumably welcome the reversal of Roe. Simple slogans and tidy categories are useful for politics but not for medicine. “Pro-life people do not understand why gynecologists talk about the need for abortion until they see a woman dying in front of their eyes because they’re pregnant,” Buskmiller said. “I think it’s possible to be pro-life, in spite of those situations. But we can’t have rose-colored glasses and think the situation is easy. It is not.”

Doctors haven’t always seen abortion as a form of health care. The text of Roe v. Wade hints at the differences among physicians in the early seventies; the Supreme Court took it for granted that some doctors would object to abortion for either moral or religious reasons. Feminist scholars have noted that the Justices seemed just as preoccupied with physicians’ rights as they were with women’s rights. “The abortion decision in all its aspects is inherently, and primarily, a medical decision, and basic responsibility for it must rest with the physician,” Justice Harry Blackmun wrote in the opinion of the Court.

Around the time that the Court was assessing the case, however, a hundred doctors signed a letter advocating a new, patient-centered approach to health care. “It will be necessary for physicians to realize that abortion has become a predominantly social as well as medical responsibility,” they wrote. “For the first time . . . doctors will be expected to do an operation simply because the patient asks that it be done.” They were arguing for a new way of thinking about medicine: at least when it comes to pregnancy, doctors shouldn’t be the deciders. Patients should.

It took many years for medical schools and health institutions to adopt this attitude. In the decades after Roe, “contraception was not considered to be a training topic worthy of an ob-gyn,” Eve Espey, the chair of the ob-gyn department at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, told me. “Abortion was just taboo. It was felt to be an activity that was dominated by older men for a profit motive.” Even by 1992, just twelve per cent of ob-gyn residency programs included training on abortion procedures.

In the early nineties, however, a major shift began – one led, in part, by students. In 1993, when Steinauer was a medical student at U.C.S.F., she founded an organization called Medical Students for Choice, with the goal of expanding abortion access. Many doctors who had started practicing before Roe, Steinauer told me, provided abortions out of necessity: they had seen women die and were committed to preventing that from happening again. “I would say my generation started thinking about it a little differently,” she said. “It was a little more activist- and advocacy-oriented.” They didn’t want a woman’s right to an abortion to be merely theoretical.

The best way to expand access to abortions, Steinauer believed, was to train more doctors to perform them. She and her fellow-students began lobbying the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education to make training on elective abortions mandatory for ob-gyn residency programs, and in 1995 this became the standard – all residents had to learn about abortion. But the next year, after pushback from Catholic hospitals and other groups, Congress passed an amendment to a public-health law, prohibiting discrimination against medical-training programs that refused to teach abortion procedures. The amendment underlined a growing tension in the field: legally, no one could be forced to perform abortions. But, culturally, pro-choice voices were growing louder within the world of obstetrics, arguing that abortion is a necessary part of reproductive health care.

In 1999, Susan Thompson Buffett, the wife of the multibillionaire Warren Buffett, bankrolled a new initiative called the Ryan Residency Training Program, which provided funding, curriculum help, and other resources to residency programs that teach abortion procedures. When I spoke with Steinauer, the director, she said that, as the program became more widely known, students who were serious about family planning began asking about Ryan rotations in their residency interviews: “They saw it as a core part of their identity as ob-gyn physicians.” (A sister program, rhedi, also provides family-medicine programs with resources to train residents about abortion.) Now, if a medical student wants to focus on providing abortions, she can choose from more than a hundred programs that follow the Ryan model, which has been adopted by roughly a third of ob-gyn residency programs. She’ll learn how to counsel patients on birth control and medication that can induce abortion in the early weeks of pregnancy, and, at some point in her training, she’ll likely perform dilation and evacuation on patients in their second trimester of pregnancy, a process that involves opening a woman’s cervix and removing the fetus. If the student wants to learn how to perform abortions on patients in complex medical situations, including those who are far along in their pregnancies, she can pursue a fellowship in complex family planning—a specialty that became fully accredited only two years ago.

And yet, even now, with the Ryan program in full force and Roe still in place, a remarkably small portion of doctors perform abortions. In a 2019 survey, published by the acog’s journal, just twenty-four per cent of ob-gyns reported performing the procedure. (In some states, nurse practitioners, nurse-midwives, and physician assistants can also provide abortions, most commonly by medication.) Another ten to twenty per cent of doctors reported that they would be willing to provide abortions and have the training to do so – but cannot, owing to hospital policies or regulations on abortion medication. Others simply don’t want abortion to be part of their medical life.

It’s hard to know exactly how many medical students and residents would describe themselves as pro-life. Surveys of Ryan residents indicate that nineteen per cent opt out of certain aspects of their family-planning training, but this doesn’t account for residents at other schools, some of whom have deliberately self-selected away from programs that follow the Ryan model. (On Buskmiller’s spreadsheet, these programs are carefully flagged.)

Ashley Womack – a friend of Buskmiller’s from high school – knew that she wanted to opt out of abortion training when she was applying for residency programs, in 2014. She purposely avoided programs in liberal states; she ended up accepting an offer from the medical center at the University of Texas, Austin, where program leaders assured her that they wouldn’t make her do anything she didn’t want to do. Womack, who is Catholic and now works in private practice in Dallas, won’t perform abortions or sterilizations. (Her personal Web site indicates that her practice follows the Catholic Church’s directives on health care.) Although she’ll counsel patients on their birth-control options, she won’t prescribe the pill or place intrauterine devices for contraceptive purposes. She told me that, when she was considering which field of medicine to pursue, she felt called to “be a pro-life voice” in obstetrics. Surveys show that roughly half of Americans consider themselves pro-life, she reasoned: “Why would it not make sense to have ob-gyns who are reflective of the population?” But, entering the field, she quickly discovered that this was not a popular view. “You need to work extra hard to be an excellent resident,” she told me. “That’s how I felt the entire time – I need to be perfect so the only thing they can complain about is that I don’t do these things.”

Soon after Womack started her residency, the program requirements changed: family-planning rotations at Planned Parenthood became mandatory. Womack knew a couple of residents whose requests not to go had been declined. So, uneasy, she showed up for her first day. The experience was upsetting: in her view, the medical staff didn’t fully counsel patients on options other than abortion. When Womack made it clear that she wasn’t going to assist with performing abortions, she was sent to the recovery room to clean chairs and hand out crackers.

During my reporting, several sources suggested that aspiring obstetricians who object to abortion should find another line of work. Meg Autry, who until recently directed the residency program at U.C.S.F., told me that many physicians who support abortion rights, particularly those who are active in family planning, feel this way. Buskmiller, who is now a maternal-fetal-medicine fellow at the U.T. Health Science Center at Houston and wants to specialize in fetal surgery, has taken a professional interest in the antagonism she perceives toward students and residents in obstetrics who don’t want to perform abortions. In 2021, she co-authored a paper published in The Linacre Quarterly, a Catholic medical journal, finding that roughly a quarter of residency-program directors expressed strong negative reactions to residency candidates who say that they won’t perform abortions. (They had much stronger reactions to other kinds of refusals, such as counselling or prescribing birth control.) “If an applicant can’t fulfill the basic duties of our program . . . it doesn’t matter how excellent they are otherwise,” one director wrote. “No one can reasonably hire a quadrapelgic police officer, even if they passed the written test with a perfect score.” It seems like this mentality will become more widespread if Roe is overturned and access to abortion training is even more limited than it is now. “When everyone has to be trained, then you have the luxury of saying, ‘Oh, let’s make sure we have a diversity of opinion so we can make the conversation broader and more robust,’ ” Autry said.

In the absolutist world of social media, the end of Roe may intensify existing conflicts between medical students who are for and against abortion. After we spoke, Buskmiller passed along screenshots of a Twitter dustup from a couple of years ago, in which a medical student got more than seven hundred likes for expressing outrage at a first-year man at her school who wanted to start a pro-life student organization: “Pro-life anything has NO PLACE in a medical school.” These are the little signals that make young doctors like Buskmiller unsure of their place in the field. “You can skate through pretty easily if you remain quiet, and if your choices . . . don’t end up on Twitter,” she said.

And yet, throughout much of the U.S., students, residents, and doctors have already been living and working alongside people whose views differ from their own. For these physicians, division over abortion is just a part of life. When Mallory Vial, a medical student who grew up in a small, conservative city in Mississippi, arrived at the U.T. Health Science Center at Houston, she expected the other students and aspiring OBs to be interested in learning about pregnancy termination – or at least engaged on the abortion issue. But “it’s been such a mixed bag,” she told me. During the spring of her first year, she became the president of the campus chapter of Medical Students for Choice. The biggest challenge she faced was apathy. “Most people in our class and at our school are more in the middle and kind of staying out of the debate,” she told me. “When there’s confrontation, they don’t really think it applies to them.”

To her surprise, Vial often found more in common with members of Physicians for Life, the anti-abortion student group, than with her other classmates. At least they cared. “When we’re having these conversations, we disagree, so there is conflict, quote-unquote,” she said. “But it’s also productive – and I think good – to see that there is diversity of opinion. . . . There’s no reason for medicine to be a monolith on this issue.” She’d attend Physicians for Life lectures and collaborate with the group on events.

As Vial was deciding where to apply for residency last fall, she debated whether to stay in Texas or pursue her education in another state. She knows that she eventually wants to practice medicine in the South – it’s where she feels most connected to patients, she said – but getting comprehensive abortion training in the region won’t be possible if the Court overturns Roe, since most Southern states will likely ban the procedure at six weeks into a pregnancy or even earlier. Despite applying to programs in various states, Vial ended up matching at the same center in Houston where she went to medical school. (Vial, along with Buskmiller and other doctors I spoke with, emphasized that her views are her own, not a reflection of her medical school or residency program.)

In some ways, Vial is typical of her generation’s progressive, abortion-supporting ob-gyn medical students. She firmly believes that the procedure should be legal and accessible, and is determined to get family-planning training in residency. She sees political advocacy as an integral part of what it means to be a doctor; she feels obligated to improve not just patients’ health but the systems in which they live. In other ways, she’s had to grapple with the future of her field before the rest of her cohort. If Roe falls, abortion will no longer be a question that ob-gyn students and residents can ignore. It won’t be a question that any doctor can ignore.

How will medical students and residents figure out their approach to abortion in a world without Roe? Depending on where in the country they live, maybe they’ll perform first-trimester abortions but nothing later in pregnancy. Maybe they’ll pick a speciality in which abortion doesn’t come up. Or maybe they’ll pursue advanced training to perform abortions at twenty weeks or later in a pregnancy. Research suggests that obstetricians already set personal limits based on the circumstances of the abortion: in one study, about a third of ob-gyns said that they wouldn’t help a woman with five daughters terminate after she found out she was pregnant with another healthy girl, for example, whereas nearly all the respondents said that they’d aid a woman with cardiopulmonary disease who might die during pregnancy.

But, if Roe is overturned, it will become that much harder for new doctors to navigate these messy boundaries – to learn how to treat real human beings with complicated stories and difficult situations. Lisa Harris, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan, wrote a paper in 2008 describing the experience of performing an abortion while she was about eighteen weeks pregnant on a patient who was roughly as far along. “With my first pass of the forceps, I grasped an extremity and began to pull it down. I could see a small foot hanging from the teeth of my forceps. With a quick tug, I separated the leg. Precisely at that moment, I felt a kick – a fluttery ‘thump, thump’ in my own uterus,” she wrote. She began crying, as though a message had been sent from “my hand and my uterus to my tear ducts,” a response “unmediated by my training or my feminist pro-choice politics.” It’s unusual to hear this kind of story about abortion; “frank talk like this is threatening to abortion rights,” she wrote. But doctors like Harris have learned to reconcile multiple conflicting truths: “I respect a woman’s request to end a pregnancy, which I understand as a request to help shape the course of her life. And I understand that a person won’t be born because of that,” she wrote in a 2019 op-ed.

But, if Roe is overturned, it will become that much harder for new doctors to navigate these messy boundaries – to learn how to treat real human beings with complicated stories and difficult situations. Lisa Harris, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan, wrote a paper in 2008 describing the experience of performing an abortion while she was about eighteen weeks pregnant on a patient who was roughly as far along. “With my first pass of the forceps, I grasped an extremity and began to pull it down. I could see a small foot hanging from the teeth of my forceps. With a quick tug, I separated the leg. Precisely at that moment, I felt a kick – a fluttery ‘thump, thump’ in my own uterus,” she wrote. She began crying, as though a message had been sent from “my hand and my uterus to my tear ducts,” a response “unmediated by my training or my feminist pro-choice politics.” It’s unusual to hear this kind of story about abortion; “frank talk like this is threatening to abortion rights,” she wrote. But doctors like Harris have learned to reconcile multiple conflicting truths: “I respect a woman’s request to end a pregnancy, which I understand as a request to help shape the course of her life. And I understand that a person won’t be born because of that,” she wrote in a 2019 op-ed.

Witnessing abortion up close can change the minds of those who are uncomfortable with the procedure, too. One female Ryan program participant in the Northeast wrote on a follow-up survey that seeing the circumstances of an elective abortion late in pregnancy helped her empathize with that choice a little more. Another woman, in the South, noted that she developed close friendships with fellow-residents who performed abortions—which changed how she saw abortion providers.

Vial and Buskmiller have never met, despite their shared affiliation with the University of Texas. Vial is about as far politically from Buskmiller as someone can be. As an undergrad, Vial was the president of her school’s Secular Student Alliance, and she wants to pursue a fellowship in complex family planning, where she’d learn how to perform abortions on women well into their pregnancies. But Vial says that she’s benefitted from knowing people like Buskmiller—the experience will help her be a better doctor to conservative patients in the South.

And even Buskmiller says that she has benefitted from having colleagues with views like Vial’s. Despite the years she has spent refining her theological and philosophical position on why abortion is wrong, she has found that theories don’t always stand up to the test of experience. She told me the story of a pregnant patient she met while she was working night shifts as a first-year resident. The woman came into OB triage several times, and her situation always seemed precarious. She appeared to be homeless and was suffering from severe mental-health problems; it became clear that the woman didn’t have a partner, and Buskmiller noticed signs that she did sex work to support herself. When Buskmiller thought about what this woman’s plan should be – for taking care of this baby, for keeping herself healthy, for not getting pregnant again before she was ready – she realized that natural family planning, a Catholic alternative to birth control that typically involves tracking the menstrual cycle, was “a woefully incomplete answer.” She was forced to ask herself, Is my world view one that really works for the world that we live in?

“The conclusion I came to is: Something can be objectively best but totally unworkable in a given society,” she said. Sometimes, she added, that means “we have to find difficult solutions and be willing to cut to the quick in our own souls.”

Written by Emma Green for the New Yorker ~ May 31, 2022