It’s time to watch Howard Hawks’s gangster masterpiece again.

The prime beneficiaries of Prohibition were gangsters, and the prime beneficiaries of gangsters were the Hollywood filmmakers who, in the late nineteen-twenties and early thirties, turned them into some of the most enticingly lurid characters ever seen in movies. The real-life gangster Al Capone was refashioned in the 1932 drama “Scarface,” directed by Howard Hawks and starring Paul Muni – a celebrated stage actor with little film experience – as a gangster so appallingly, flashily fascinating that the movie was accused of making the criminal life look too appealing. Hawks’s “Scarface” was “The Wolf of Wall Street” of its day, and, like Martin Scorsese’s extravagant, exuberant 2013 drama about financial grifters, the film’s allure and enticements are a crucial part of its substance. (“Scarface,” long available to stream on a variety of platforms, is newly available to stream on the Criterion Channel, in a clear and vivid transfer.)

The prime beneficiaries of Prohibition were gangsters, and the prime beneficiaries of gangsters were the Hollywood filmmakers who, in the late nineteen-twenties and early thirties, turned them into some of the most enticingly lurid characters ever seen in movies. The real-life gangster Al Capone was refashioned in the 1932 drama “Scarface,” directed by Howard Hawks and starring Paul Muni – a celebrated stage actor with little film experience – as a gangster so appallingly, flashily fascinating that the movie was accused of making the criminal life look too appealing. Hawks’s “Scarface” was “The Wolf of Wall Street” of its day, and, like Martin Scorsese’s extravagant, exuberant 2013 drama about financial grifters, the film’s allure and enticements are a crucial part of its substance. (“Scarface,” long available to stream on a variety of platforms, is newly available to stream on the Criterion Channel, in a clear and vivid transfer.)

For Scorsese, the swaggering financial culprit is a magnification of the ordinary cravings of his viewers, of himself, of everyone. For Hawks, the gangster is the perversion of cool – a magnification, via crime, of the swagger, the style, the audacity that could readily invigorate any of the other bold enterprises that Hawks filmed, whether combat or auto racing, journalism or business. What’s more, in “Scarface,” Hawks himself is doing much of the swaggering, contributing much of the daring and the style. He’d started his directorial career in 1926, and had made ten films (including some extraordinary silent comedies and the pioneering early talking picture “The Dawn Patrol”) by the time he shot “Scarface,” in 1931. By then, he’d established a style of terse understatement, of extreme visual restraint, like a pictorial Hemingway. But Hawks’s first ten films had been produced by Hollywood studios; “Scarface” was produced by the embodiment of swagger himself, the mogul Howard Hughes, who, as an independent producer, sought to crash the Hollywood gates, and who encouraged Hawks to make a splash by giving his imagination free rein. The result is a display of directorial bravura and bravado that stands out to this day as a high point of invention, audacity, and startling idiosyncrasy – in Hawks’s career and in the history of cinema.

The movie’s first shot is a mighty display of stylistic brilliance that relies on clear and simple action to set contrasting moods of jolting, dissonant complexity: a three-minute-plus tracking shot that starts up high at a streetlight at Twenty-second and Wabash (setting the action in Chicago), descends to a sidewalk where a waiter stands outside a restaurant after a big bash, accompanies him into the restaurant for his cleanup, and, finding a Mob boss there with his cronies, culminates in a murder that’s shown entirely in shadows. The titular protagonist, Tony Camonte (Muni), isn’t the gunman – that would be his bodyguard and right-hand man, Guino Rinaldo (George Raft, in a star-making turn). Tony makes his appearance several scenes later, in a barbershop, where a police detective (C. Henry Gordon) comes to arrest him and Rinaldo for the murder; Tony emerges from under a hot towel with a defiant sneer and greets the detective with an insolent, sexualized provocation – striking a match on the officer’s badge. (It’s also in the barbershop that Raft introduces his trademark gesture – repeatedly tossing a coin in the air – which became an iconic symbol of gangster cinema itself.)

The drama is centered on Tony’s effort to take over the crime family of Chicago, headed by Johnny Lovo (Osgood Perkins), in which Tony is an underling, and then to take over the city’s entire gangland empire. The story is based largely on real-life characters and incidents (its principal screenwriter, Ben Hecht, had been a journalist in Chicago and knew Capone and other gangland figures), and it’s mainly a tale of Tony’s overweening ambition being matched with the daringly insightful strategy and pathological amorality necessary to carry it out – and also his high-wattage personality, which enthralls his criminal cohorts and turns Tony into a modern figure of mass-media mythology.

After the restaurant hit by Tony and Rinaldo, Lovo is the new king of the South Side – but he’s afraid to make a move on the Irish gang that controls the North Side. Tony has no such qualms, telling Rinaldo that Lovo is “soft” and boasting that, one day, he’s “gonna run the whole works.” Here, Tony delivers his credo: “Do it first, do it yourself, and keep on doing it.” He takes the fight to the North Side and sparks a bloody gang war – which he wins, in part through the horror of what became known as the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Then Tony moves in on Lovo – and, of course, eventually rubs him out and takes over his gang – but not before attempting to lure Lovo’s girlfriend, Poppy (Karen Morley), away from him. Lovo is a killer with a veneer of refined manners, and Poppy, with a sheen of sophistication to go with her shimmery and glittery accoutrements, is at first merely amused by Tony’s blithe vanity and oblivious crudeness. (“You’re such a funny mixture,” she tells him, and his response would find its echo decades later chez Scorsese: “How do you mean, you think I’m funny?”) The scene in which Tony wins her over is one for the ages, done with a Hawksian gesture that has entered the history books: at a night-club table, Poppy puts an unlit cigarette to her lips, Lovo and Tony simultaneously offer her lit matches, and she chooses Tony’s.

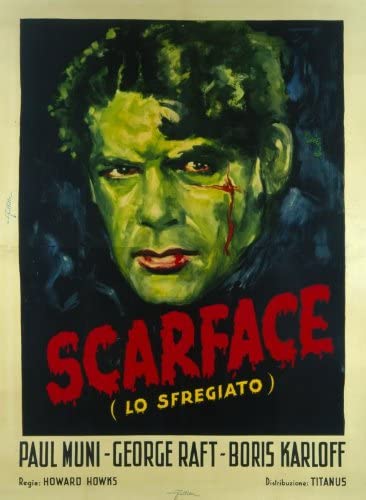

Paul Muni’s role as Tony Camonte, in Howard Hawks’s “Scarface,” is one of the most hyperbolically theatrical yet cannily cinematic performances ever filmed.Photograph courtesy of the Criterion Collection

But the main woman in Tony’s life is his sister Cesca (Ann Dvorak), who’s eighteen and longing to escape the family confines. She lives with their mother (Inez Palange), an Italian immigrant who rues and fears Tony’s evil ways, in a poor but well-kept house. Cesca is something of a free-spirited partyer, but Tony, pathologically controlling of what he considers the family honor, tries to keep her from dating, even from dancing, and the implications of his incestuous passion are unmistakable – and, after Cesca begins to date Rinaldo, devastating.

Muni’s role as Tony is one of the most hyperbolically theatrical yet cannily cinematic performances ever filmed. The absurd exaggerations that Muni delivers a boisterous, highly inflected but non-stereotypical Italian accent (his pronunciation of “pretty” as “put-ty” is an Oscar in itself), a flashy repertory of gestures rich in air-kisses and aggressive gesticulations, an alternation of cool composure and feral ferocity as he dispenses violence, a brash overconfidence as he boasts to women—make him seem like the only character in this black-and-white movie who’s filmed in peacock-bright color. His bluster and terrifying rage, his juvenile glee in anticipating murder and his ice-cold efficiency in committing it – all to the tune of the sextet from Donizetti’s opera “Lucia di Lammermoor,” which he whistles throughout – evoke a terrifying tangle of self-dramatizing impunity, a force of irrepressible will and uninhibited power that perverts the shining story of American-immigrant success into a predatory nightmare that’s inseparable from the hubris of Tony’s psychosexual violence.

Tony’s sexuality is tinged with ambiguities that hint at the torment of repressed desires. Homoerotic touches run throughout the film, as when Poppy wonders whether his jewelry seems “effeminate” and Tony, who doesn’t know what the word means, presumes that it’s a compliment. Tony’s defiance of Lovo in taking over a beer-running racket is marked by Angelo (Vince Barnett), Tony’s diminutive, illiterate, meek, and bewildered sidekick and ostensible secretary, who deftly grabs a long, sharp pencil from the inside of Lovo’s vest and wets its tip in his lips before passing it along to Tony, suggesting a complicit intimacy. Such gestural touches, a hallmark of Hawks’s work, puncture the fabric of the drama and suggest the roiling psychological magma beneath.

Throughout the film, Hawks finds inspiration in visual and emotional incongruities suggested by the gangster life: at a Mob hit at a bowling alley, where the camera follows a rolling ball after its bowler, the victim, has been gunned down; a version of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, also done entirely in shadows; a scene in which Angelo, arguing by phone in his thick accent and fractured grammar, pulls out his gun to shoot the handset. The greatest of these unexpected contrasts is the movie’s most colossal set piece – one that outdoes even the opening shot – in which Tony, Rinaldo, Poppy, and Angelo are at a restaurant that Tony’s gangland rivals pulverize with a sustained barrage of machine-gun fire. Tony, Rinaldo, and Poppy survive by crouching on the floor, and even recover one of the weapons – the first time they’ve seen handheld machine guns, which they’re soon to procure in large and deadly numbers. Angelo, however, is at the back of the restaurant, at a pay phone, taking a message for Tony, as gunfire sprays the booth all around him (destroying a coffee brewer, which wets his clothing). He emerges unscathed, after complaining to the caller that he can’t hear because of all the noise.

These antics evoke, with the help of Hawks’s own avid and astonished camera gaze, the absurdity of a world in which a figure like Tony can thrive, however temporarily. (I’ll avoid spoilers and merely suggest that, unlike Capone, he isn’t arrested for tax evasion.) Hawks digs in and delights in the spectacle, and, without in any way minimizing the horror of the gangster life, he avows its horrific sublimity – a quality that explains why a certain kind of strong character, with strong desires and weak morality, might choose this path. As in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” if there weren’t pleasures that inhere in and derive from certain misdeeds, no one would bother to commit them – and, if viewers needed Hawks’s personal seal of disapproval to know that murder is evil, it’s too late for them.

That seal is nonetheless what censors – both those who enforced the Hays Code (already in effect but less stringent than it would become in 1934) and those who enforced local codes – wanted. The movie was withheld until changes were made to several scenes and a prologue of denunciation was filmed, along with a silly, interpolated scene of concerned citizens and a tut-tutting police official who calls for strict gun laws, sped-up deportations, and, if necessary, martial law. (The prologue is no longer part of the film; the interpolation is.) What emerged, when “Scarface” was finally released, in March, 1932, was the most floridly and excitingly inventive talking picture made in Hollywood prior to Orson Welles’s “Citizen Kane,” another masterwork of American hubris. And, before Welles’s own starring turn, Muni’s was the most grandly screen-bursting performance ever seen. Though “Kane” outpaces “Scarface” in social history and in its comprehensive reconsideration of narrative form, it can’t touch Hawks’s film in perverse contradictions and psychological underworlds. “Scarface” remains, even now, a high point of cinematic modernity.

Written by Richard Brody for The New Yorker ~ July 6, 2021