… Choppers Got Shot up so Bad he Had to Use 3 Different Ones

Editor’s NOTE: There are days in this land of ours today that I look back to other days. Yes – I have shared some of my story on this site before, and you can find them if you so desire. Singer Charlie Daniels told one hell of a story with his song, “Still in Saigon,” but his direction was different than the one which I chose in life. Yes – I feel much the same way in America in 2019 – but look back on that experience with different feelings than that which the song portrayed. I spent 21 months with the 498th Dust Off (Med-Evac) Group – and have never regretted one day of that service. Then I read the stories of Bruce Crandall and his Co-Pilot, Ed “Too Tall” Freeman – and I am home once again – yeah, “Still in Saigon.” ~ Ed.

Most fans of war films have probably seen the movie We Were Soldiers, but did you know that hidden in that movie is a Medal of Honor-winning event? Greg Kinnear plays a hard-charging helicopter pilot named Bruce Crandall. For his actions during that battle, Crandall would be awarded the USA’s highest decoration.

Most fans of war films have probably seen the movie We Were Soldiers, but did you know that hidden in that movie is a Medal of Honor-winning event? Greg Kinnear plays a hard-charging helicopter pilot named Bruce Crandall. For his actions during that battle, Crandall would be awarded the USA’s highest decoration.

“The officer commanding the medevacs looked me up to chew me out for having led his people into a hot LZ, and warned me never to do it again. I couldn’t understand how he had the balls to face me when he was so reluctant to face the enemy.”

Born in Olympia. Washington in 1933, Bruce Crandall was drafted sometime around his 20th birthday and then commissioned out of Engineer OCS the following year.

Gaining his wings in fixed and rotary aircraft, he went on to serve in various posts that allowed him to help develop the world’s first helicopter assault tactics. This training and skill would serve him well in just a few years’ time.

Gaining his wings in fixed and rotary aircraft, he went on to serve in various posts that allowed him to help develop the world’s first helicopter assault tactics. This training and skill would serve him well in just a few years’ time.

In July 1965, Crandall was posted to Vietnam and assigned to command Company A of the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion. This unit was based out of Camp Radcliff, An Khe, South Vietnam. Among the troops they would be transporting were units descended from the famed 7th Cavalry.

Aerial view of An Khe airfield under construction, 1965.

On November 14th, 1965, orders were received which sent the 7th Cavalry/Airmobile to a location at the foot of the Chu Pong Massif, a large mountain plateau known to house NVA and VC units. This destination would be forever known as LZ X-Ray.

The plan was to draw out the guerrillas so they could be destroyed by the supporting Artillery and Air Support. This plan worked better than anyone could have hoped. While the enemy obliged the American desire for battle, they did so in far greater numbers than expected.

Heavy fighting broke out from several directions, causing smaller American units to be cut off and heavily damaged. Three battalions of NVA regulars numbering over 1600 men swiftly surrounded the tiny landing zone and the Americans.

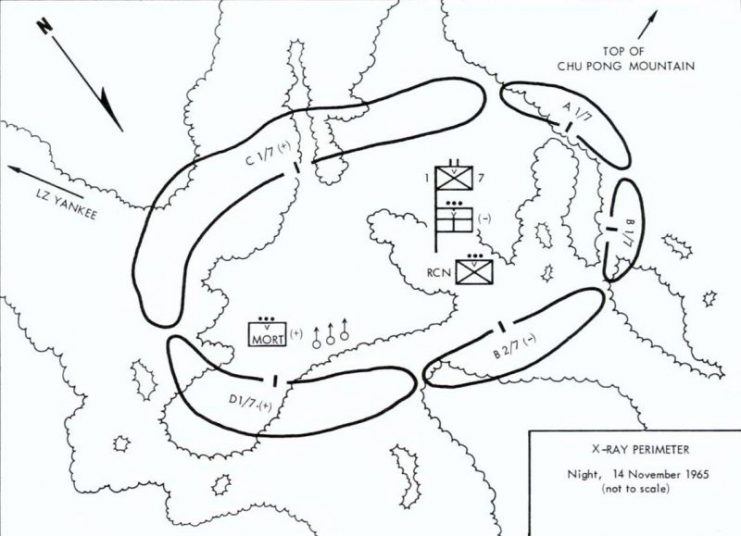

X-Ray perimeter, night of November 14.

Surrounded by the enemy, the American troops now depended on air support for supply, casualty evacuation, and even their survival.

Due to his expertise, Crandall was involved in the operation from the very beginning, including the planning of the sorties. The size of the landing zone necessitated that the troops be brought in three waves. This required separate flights of over 30 minutes each way.

Once combat began, his helicopters shifted roles from being troop transports to angels of mercy. Flying in with desperately needed ammunition and supplies, they would depart carrying badly wounded and dying men.

1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry troopers landing at LZ X-Ray

With his aircraft often flying with well over their maximum takeoff weight, Crandall brought supplies which enabled the 7th to hold out for more than three days against superior forces. During the battle, Crandall would continue to fly operations far beyond established crew rest standards.

Meanwhile, the NVA were not merely sitting by while the Americans flew in and out. Machine gun nests and small anti-aircraft guns began to pop up and fire on the helicopters as they appeared. If a helicopter became too damaged from enemy fire to continue, Crandall would switch to another helicopter, load up, and head back to the battlefield.

North Vietnamese regular army forces

Specially equipped Medical-Evacuation (medevac) choppers had also been developed as a part of the overall Air Assault tactics. These were used from the very first to go in and get wounded men from LZ X-Ray.

However, a problem occurred when crews refused to fly into LZ X-Ray due to the risk of enemy fire. As a result, Crandall and fellow Medal of Honor winner, Ed Freeman, decided that they would take on the additional task of flying out the wounded men.

In the course of just one day, it is estimated that Crandall flew between 14-22 flights (official records are lacking) in and out of the combat area. Crandall acted with total disregard for his own safety. He was always under fire, frequently in a badly damaged helicopter, and continued his runs long into the night.

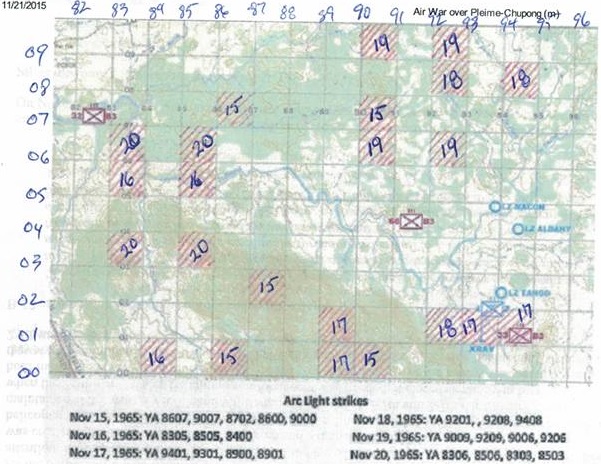

B-52 strike on NVA troop positions, November 15–20. Photo: Tnguyen4321 CC BY-SA 3.0

All of these flights were conducted in helicopters with no armament and very little of what could be considered armor. At this stage in the war, helicopter gunships were experimental and not yet available for service.

Crandall’s actions during the battle would gain him the Distinguished Service Cross. In 2007, President Bush presented him with the upgraded Medal of Honor for his heroic actions.

President Bush presents the Medal of Honor to retired Army Lt. Col. Bruce P. Crandall.

In one part of the movie, Crandall threatens the other pilots for being cowards. It has never been established with certainty as to whether this really happened, but given the amount of courage and craziness that Crandall displayed, it would not be surprising if it had.

For the entire three days that Crandall was re-supplying the troops, American planes all the way up to B-52 bombers were working to keep enemy troops clear of the perimeter.

After this battle, Crandall didn’t just sit back and relax. He was cited for bravery later in the war for being the only pilot both willing and able to come to the aid of a cut off unit at night.

Following the war, Crandall left the Army, became engaged in city administration, and then retired to Washington state, where he lives to this day.

Written by Joseph O’Brien for and published by War History Online ~ November 20, 2018

Bruce Crandall

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml