By March 1969, the U.S. Army was under a new commander, General Creighton Abrams, and forces had peaked at 543,000 in country, as peace talks had begun and a new plan was underway for the “Vietnamization” of South Vietnam and the “pacification” of any remaining communists in the countryside, the hamlets and villages. Some ninety thousand North Vietnamese and Viet Cong soldiers remained in the South, strewn throughout the countryside and in certain sanctuary villages sympathetic to the Ho Chi Minh brand of communism, just waiting for orders to mount attacks at a moment’s notice.

It was around this juncture in the war that the counterinsurgency effort under the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support [CORDS] implemented the Phoenix Operations, run by the CIA, which facilitated a concerted effort to eliminate the Communist political machine and mechanisms by capturing or killing the Viet Cong leaders in the villages and provinces. The operation ran throughout every district in South Vietnam using a combination of conventional military forces, militia, police and intelligence operations never before witnessed anywhere on such a large scale.

Along with the pacification of the countryside, ongoing efforts to “win the hearts and minds of the South Vietnamese people” were being conducted, although no real consensus had ever been realized in regard to what this actually meant. And, the Phoenix program was basically proving to be a failure, resulting in no high-level, hard-core communists being captured or eliminated, although some low and mid-level cadres were eliminated; other problems were created by this program, when some South Vietnamese officials began abusing the program and using it to carry out their own personal vendettas and/ or started accepting bribes from the Viet Cong to release many of their captured cadre. An unbelievable level of corruption across all segments of the South Vietnamese government ensured the failure of these efforts.

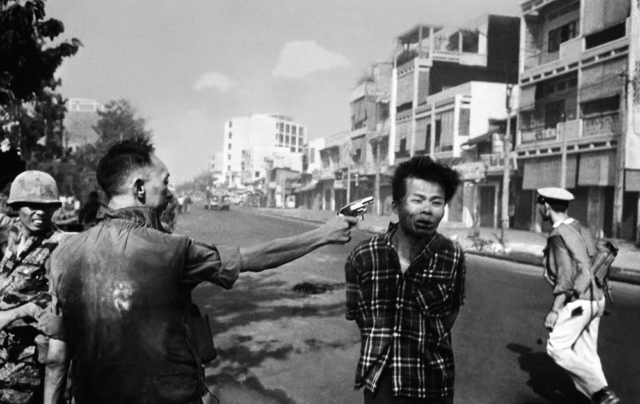

‘The Saigon Execution‘ by Eddie Adams/Associated Press – On February 1st 1968 – during the Tet Offensive – General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, director of South Vietnam’s national police force, executed a Viet Cong prisoner on the streets of Saigon.

It’s worth noting that the U.S. was also repelling communists from Laos and Cambodia during the entire Vietnam War. America had been in Laos since 1959, fighting the Pathet Lao Communists who were being funded and supplied by Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh’s Communists as well as the Soviet Union. Ho was intent on ultimately taking and controlling Laos, too. America started going after Viet Cong bases in eastern Cambodia on April 28th 1970, where the Viet Cong were put in close proximity to Saigon by way of the Tay Ninh corridor, as well as others, set in motion several historic hard-fought battles by 1st Cavalry, the 1st and 25th Infantry and the U.S. 5th Special Forces among others; all of this at a time when the U.S. was preparing to withdraw from Vietnam and attempting to prepare South Vietnam’s government and military to capably take over full control of their country and its defense.

Once the anti-war crowd back home in America became aware of the expansion of the Indochina Wars, exceptionally violent demonstrations broke out, and in response to the violent demonstrations, President Richard Nixon surrendered to the outcry of the radicals and allowed them to dictate the execution of the war and policy in Vietnam, and he imposed geographical limits and time limits on operations in Cambodia, which emboldened the enemy and allowed the communists to stay beyond reach, to live to fight another day.

Years after the fact, many opponents of the Vietnam War would point to the Battle of Hamburger Hill, otherwise known as Hill 937 and what they viewed as the underlying insanity of taking a hill that help absolutely zero military strategic value. But, as Major General Melvin Zais, commander of the 101st Airborne Division, would later say:

“My mission was to destroy enemy forces and installations. We found the enemy on Hill 937, and that is where we fought them.”

Approximately a month after the 101st Airborne abandoned the hill and left A Shau Valley, the North Vietnamese were free to use it again, for whatever purpose they had been previously.

Key to the success of the North Vietnamese war effort was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and President Richard M. Nixon began breaking their supply line by mounting one of the most intense and prolific bombing campaigns seen in modern times, as all sorts of bombs fell on the enemy along with tons of napalm that seared flesh from bone and resulted in an excruciating, painful death for the enemy, and sometimes poor unfortunate innocent South Vietnamese civilians, as memorialized in the photo by Nick Ut of the Associated Press on June 8th 1972. The bombing campaign started in March of 1969 and ran until January of 1973, when it ended as part of the Paris Peace Accord. And, by many accounts, this is what allowed the Noth Vietnamese to regroup, resupply and get back in the fight full force, when they were just about on their knees and within about two or three weeks of surrender.

Kim Phúc, center, running down a road naked near Trang Bang after a South Vietnam Air Force napalm attack

It’s pretty eye-opening to look at the historical progression of this war in conjunction with the statements of all the U.S. Presidents involved in conducting it. They all seemed to be in complete favor of doing all we could to stop the communists from spreading across Indochina, until it became politically expedient — looked bad in the polls — or deemed necessary to back away from their previous enthusiastic support, as witnessed in the following words:

“The loss of Indochina would be the loss of Southeast Asia. The United States must help.” ~ Pres. Eisenhower, 1954

“We are not going to withdraw … This is a most important struggle.” ~ President Kennedy, 1961

“We will not be defeated. We will stand in Vietnam.” ~ President Johnson, 1965

“Let me make one principle of American policy absolutely clear: the United States will not permit the independent existence of South Vietnam to be destroyed by force.” ~ Pres. Nixon, 1969

Fast forward to 1975. The so-called “peace treaty” signed in Paris did not hold and the North Vietnamese Communists were soon on the offensive again, advancing on a weakened South Vietnamese Army and all that was left of the U.S. Armed Forces was 800 Marines, along with some 5000 U.S. citizens still In Country.

On March 10th 1975, the South Vietnamese Army was handed a sound trouncing, when two North Vietnamese divisions rolled over it at Ban Me Thuot, the capital of Darlac province, just two hundred miles north of Saigon, which amounted to an incredibly significant blow, and it paved the way for the NVA to head eastward toward the coast with substantial tank reinforcements. The NVA proceeded to cut South Vietnam in half, and by April 2nd, the NVA had Saigon’s forces in the northern half of South Vietnam trapped between North Vietnam and a massive number of Communist units flooding in from the Ho Chi Minh Trail and Cambodia. Fifteen North Vietnam Army divisions surrounded the Saigon area by April 25th, and all that stood between them and the victory they had been seeking for decades was four infantry divisions, an airborne brigade, an armored brigade, and two ranger regiments.

Early in April 1975, the situation was looking increasingly dire to all with eyes to see, and it was fast apparent that step by step numerous tank-led North Vietnamese Army columns were seizing South Vietnam and would not be stopped. Ho Chi Minh’s campaign had begun with the January 6th 1975 fall of Phouc Binh, the first provincial capital to be taken by the North Vietnamese Communists in the two years following the signing of the Paris peace agreement. This defeat of the South Vietnamese Army, a mere seventy-five miles north of Saigon was accomplished by two North Vietnamese divisions, and it was the handwriting on the wall, as this pattern was repeated over and over again.

Vietnamese refugees crowd aboard the Military Sealift Command ship Pioneer Contender to be evacuated to areas further south on April 23rd 1975.

Women and children hide in a muddy canal at Bao Trai, about twenty miles west of Saigon, in order to avoid intense fire from the Viet Cong. The war ended on April 30th 1975 with the fall of Saigon to the North Vietnamese communists.

A general panic had taken control of the civilian population and the South Vietnamese military and political leaders as well, as early as April 1st, when it was learned Pleiku had been abandoned and North Vietnamese Army Regulars and Viet Cong were advancing down from Binh Dinh province and the Central Highlands and would soon overrun Nha Trang. As refugees fled Nha Trang and headed toward Saigon, 275 miles to the south, the news traveled fast and South Vietnamese and Americans made plans and attempted to flee Vietnam as fast as possible. And as everybody fled into Saigon, it wasn’t long before many fear-inspired riots broke out near and around the U.S. Embassy.

An American official punches a man in the face trying to pry him off the doorway of an airplane already overloaded with refugees seeking to flee Nha Trang, South Vietnam on April 2nd 1975 [credit, NYTs]

Saigon and South Vietnam was set to fall, and there was no avoiding that fact; but despite this certainty and evacuation plans discussed in mid-April, Graham Martin, the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam, resisted any notion of evacuation, although he did reduce the size of embassy personnel. Military efforts to persuade Martin to call for a general evacuation were also met with anger, and on April 12th, he told a delegation from the 9th Amphibious Brigade – given the task of supplying helicopters and security forces for the evacuation – that he would not tolerate any outward signs that the U.S. intended to abandon South Vietnam. From this point on, all planning was redirected through Brigadier General Richard Carey, commander of the 9th MAB, and in the meantime, the military situation worsened, and the North Vietnamese surrounded Saigon. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned on April 21st 1975.

Fortunately, good men and women from the military and civilian ranks had formulated a fairly decent evacuation plan in early April – Frequent Wind [Opton 4] – focused on a cooperative effort between the U.S. military and Air America, which was “a civilian concern”, which would later be discovered to have been a CIA front, too. Air America’s Bell UH-1 Hueys were determined to be more suitable than the heavy Marine helicopters for evacuation operations from the rooftops in downtown Saigon, and the airline pledged to have twenty-five of its twenty-eight helicopters available at any given time. Due to a shortage of pilots, they would have to fly without any co-pilots, but Air America was used to assuming such risks.

Thirty-seven buildings in downtown Saigon were assessed on April 7th by Nikki Fillipi, Air America’s representative to the Special Planning Group of the Evacuation Control Center at the Defense Attach Office [DAO] compound, and working with Marine Laison Officer, Lt. Robert Twigger, they shortened a two-day task to ten hours and identified thirteen buildings that would work well for the evacuation. Three eighteen-hour days followed, in which Fillipi supervised crews in removing all obstructions that would possibly prevent safe helicopter movements in and out of the landing zones. An “H” was painted on each rooftop, indicating where the pilots needed to plant the helicopter skids, which guaranteed that the ‘copter could land and take off in any direction with its rotors clear.

On April 28th, Paul Velte, managing director and CEO of Air America, was in the office of Var Green, Air America V.P., at Tan Son Nhut, with his back to the window, when jets passed overhead a little after 6:00 P.M., and suddenly bombs began to fall, making the window glass shatter. Five Cessna A-37 Dragonfly jets attacked the Vietnamese Air Force side of the field, destroying three Fairchild gunships and several Douglas C-47 transports. It soon became obvious that this aerial attack was the beginning of the North Vietnamese offensive against Saigon, rather than a coup as some initially thought.

Tan Son Nhut came under intermittent rocket and artillery fire at sundown, but frequent secondary explosions from fuel and ammunition hit in the initial air attack gave the impression it was being continuously shelled through the night. As 4:00 A.M. arrived on April 29th, the NVA conducted a major rocket and artillery barrage on Tan Son Nhut, with fifty rounds falling each hour. It was a chaotic scene as soldiers, pilots and all support personnel sprang to defend the post, but others sought refuge in 8×8 feet sandbag pits, crying secretaries and some South Vietnamese Catholics praying on their rosary beads, anticipating being overrun by hordes of Viet Cong communists crashing through the fences any minute, which prompted on Air America pilot, a Baptist, to say in later years, “wished that I had a few rosary beads myself”.

Shortly before 11:00 A.M. on April 29th 1975, a complete evacuation order finally came down to all personnel. Americans in Saigon had previously been given a code that would indicate it was time to evacuate, and they kept it quiet in order to prevent a city-wide panic, for what little good that did. All U.S. personnel knew they had to go immediately to the nearest designated assembly point, when the American radio Service announced that the temperature in Saigon was “105 degrees and rising” followed by Bing Crosby singing “White Christmas“.

Many personal stories came out of that day, some of extreme sorrowful loss and death and some of narrow escapes, successes and triumphs, and in all the chaos, it’s a wonder that anyone got out at all. Helicopters were overloaded and barely topped the buildings, while some crashed aboard Naval vessels awaiting evacuees. Other pilots faced panicked passengers like one fat CIA agent who nearly caused the ‘copter he was in to crash, along with rotors flying through the air from crashed ‘copters to pierce the engine of another. They even lost their refueling station that day and had to fly an additional seventy miles to ships off the coast in order to refuel. They pushed their ‘copters to their limits and beyond and they flew themselves to the limits of their ability and beyond.

Over the month of April 1975, the total evacuations, including those conducted during the two-day operation Frequent Wind — the largest helicopter evacuation in history – resulted in 6000 Americans being flown out, civilians and U.S. personnel alike. In addition, approximately 65,000 South Vietnamese, including most of the local hires for the State Department and CIA were also flown out to safety.

On the morning of April 30th 1975, Thomas Polgar, the CIA Chief for Saigon, cabled the CIA Headquarters stateside, saying, “… this will be the final message from Saigon … It has been a long hard fight and we have lost.” Saigon fell before the day was done.

Today, ask a million Americans what they think about the U.S. involvement and you’re likely to receive a million completely different responses, but it did leave a deep scar on the American psyche, for a litany of reasons. More often than not, the fall of Saigon and South Vietnam in general is seen in a negative light, a bitter end to the long American effort to help South Vietnam stand independent and alone to effectively defend itself. The failure to achieve this wasn’t so much in the advice and support from the U.S. which couldn’t overcome or full compensate for South Vietnam’s own political shortcomings; over a span of some twenty years, several regimes had failed to find common cause with the largest majority of South Vietnamese or make proper, full and honest use of their social, economic and political resources to foster a popular base of support, to in effect win the hearts of their people. While conventional North Vietnamese and Viet Cong Communist combat units ended the war, it was disaffection and insurgency among the people of South Vietnam that made this end result possible.

Approximately 2.5 million more South Vietnamese were murdered in just a few short years after the war ended, by their new Communist masters, who targeted teachers, doctors, lawyers and other professionals educated and intelligent enough to present the new Communist overlords with a problem and more insurgency or potential rebellions. Many others were sent to “re-education camps”. It would have been better for them if they had chosen to fight to the death or on to victory, whatever victory meant to them at the time.

We’ll all be together again – soon enough!

May 1, 2025

Justin O. Smith ~ Author

~ The Author ~

Justin O. Smith has lived in Tennessee off and on most of his adult life, and graduated from Middle Tennessee State University in 1980, with a B.S. and a double major in International Relations and Cultural Geography – minors in Military Science and English, for what its worth. His real education started from that point on. Smith is a frequent contributor to the family of Kettle Moraine Publications.