One article from 1966 written by Francis FitzGerald, I found to be extremely thought provoking, even if it was written from a leftist perspective. She wrote, in part, painting a vivid picture:

“Before entering Saigon, the military traffic from Tan Son Nhut airfield slows in a choking blanket of its own exhaust. Where it crawls along to the narrow bridge in a frenzy of bicycles, pedicabs, and tri-Lambrettas, two piles of garbage mark the entrance to a new quarter of the city. Every evening a girl on spindle heels picks her way over the barier of rotting fruit and onto the sidewalk. Triumphant, she smiles at the boys who lounge at the soft-drink stand, and with a toss of her long earrings, climbs into a waiting Buick.

Behind her the alleyway carpeted with mud winds back past the facade of new houses into a maze of thatched huts and tin-roofed shacks called Bui Phat. One of the oldest of the refugee quarters, Bui Phat lies just across the river from the generous villas and tree-lined streets of French Saigon. On its tangle of footpaths, white-shirted boys push their Vespas past laborers in black pajamas and women carrying water on coolie poles. After twelve years and a flood of new refugees, Bui Phat is less an urban quarter than a compost of villages where peasants live with their children. The children run thick underfoot. The police, it is said, rarely enter the quarter for fear of a gang of teen-age boys whose leader, a young army deserter, reigns over Bui Phat.”

Saigon Fifty Years Ago

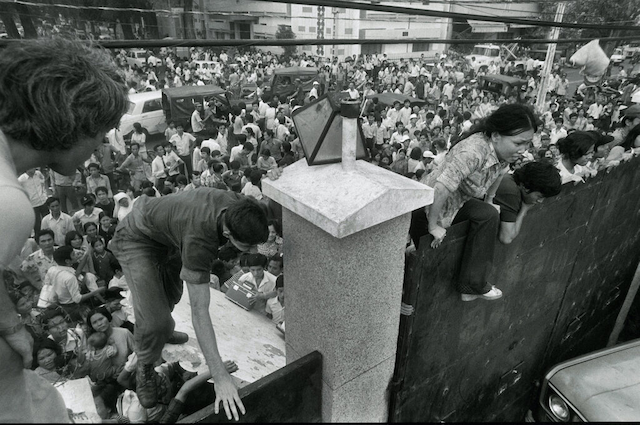

South Vietnamese civilians scale the fourteen feet tall wall of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon on April 29th 1975, as panic set in and everyone was trying to catch the last few helicopters out of Vietnam with the American departure from Vietnam.

“What whisper hisses in the inner ear ‘take cover’? Ah, and then the boy is dead, others dead or dying, and the evil laps out from bits of hot lead across the nervepools of the nation.” ~ Gena Ford, Lines for Hard Times, May 1967

One of the more controversial junctures of United States history was the U.S. execution of a war in Vietnam, where several U.S. administrations sent supplies, weapons and soldiers to fight on the side of the capitalist, freedom-loving South Vietnamese against the communist North Vietnamese followers of Ho Chi Minh and the totalitarianism he offered. It was a war that could have easily been won, if not for weak men succumbing to the will of a fairly significant vocal and violent minority of radicals and the numerous ongoing protests and acts of violence that shook the nation in the 1960s, that finally culminated with the fall of Saigon on April 29th 1975, fifty years ago.

Evacuees are helped aboard an Air American helicopter perched atop the Pittman Apartments on April 29th 1975.

Despite all warnings from the Founders in regard to foreign entanglements, the aftermath of WWII and President Franklin Roosevelt’s betrayal of Eastern Europe to the Soviet Communists opened America’s eyes to the realities of communism and all it meant for any nation subjugated by communist masters, whether implementing the communist doctrines of Marx or Mao, and subsequent U.S. presidents saw a necessity to help any nation under assault by communists in order to halt the fall of every nation in the world to this evil ideology, one by one – the view that became known as the “Domino Theory”. This view was largely validated as both the Chinese and Russian communists attempted to expand after WWII, when both sent aid, military supplies and weapons and “advisors” to the communists in Korea in the 1950s and the communists in Vietnam in the 1950s and 1960s.

The world and America saw communism firsthand as something to be reviled and rejected and opposed. Communist leaders showed themselves to be monsters, and communism itself was far from the beautiful fairytale of all peoples of the world joining hands and singing “kumbaya” in selfless unison and in service to a one world government where everyone had every need met by the government and lived happily ever after. The communist world was in fact one filled with the murders of millions of dissidents and opponents, severe poverty and starvation and general misery for all, except for those who had taken and held power simply for the sake of power itself, often taking a nation’s wealth for themselves, their own delusional visions and self-aggrandizement without any real care for the wellbeing of the people under their control.

If fighting for the principles of freedom wasn’t worth the cost to Americans and the rest of the Free World, why did they fight against Germany’s National Socialists? Why bother? Why not just surrender the principles of freedom up to evil and tyranny then?

No matter that death is the final step in our lives, it doesn’t mean we must take a fatalistic view of the world and simply stand idly by while tyranny and evil take hold of any country, especially if it is our own country, much as we have seen occur over the past sixty years in America. It makes sense to stand for people defending the principles of freedom and liberty in their own land, just as we fought for our own in America’s earliest times, without wasting a step or falling asleep at the helm of leadership for a second and without fear of making a mistake when we know our cause to be righteous; and we cannot fear breaking as we are but men, not angels or beasts, but men, who, at the end of the day, do not want to find our own nation standing alone, an island of freedom in a vast ocean of tyranny preparing to fight to the death for its survival.

And so enters Vietnam Life and Death in Saigon.

An American officer serving with the South Vietnam forces poses with group of Montagnards in front of one of their provisionary huts in a military camp in central Vietnam on November 17th 1962. They were brought in by government troops from a village where they were used as labor force by communist Viet Cong forces. The Montagnards, dark-skinned tribesmen numbering about 700,000, live in the highlands of central Vietnam. The government was trying to win their alliance in its war with the Viet Cong.

The United States sent the first U.S. advisors to French Indochina aka Vietnam in 1950 to support the French, who essentially retreated and surrendered all claims to the area on July 21st 1954, via the Geneva Accord, after its catastrophic defeat at Dien Bien Phu on May 7th 1954. This resulted in the North-South divide of Vietnam along the 17th parallel and the independence of Cambodia and Laos, which were to stay neutral, while French soldiers remained in the South and Ho Chi Minh’s forces in the North; both were supposed to forego any outside alliances, and elections were to be held in 1956.

The U.S. didn’t sign the agreement and quickly went about the business of helping to establish a South Vietnamese government led by Ngo Dinh Diem, who was very unpopular with the people themselves. The U.S. also proceeded to support the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, which was structured as a counterforce to any armed attack on any nation in the region.

Several current military strategists and experts have since suggested the Vietnam War was unwinnable, largely because of nepotism and corruption in the South Vietnamese government, the involvement of the Soviet Union and China on the side of North Vietnam and, according to some, the lack of will to fight for themselves in the South, despite many assertions to the contrary. However, installing several subsequent unpopular presidents to follow Diem didn’t help the cause for a free and independent South Vietnam either.

In 1965, there were twenty-five thousand U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam, by the time the first 3500 Marines from the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade arrived in Da Nang on March 8th 1965, after their orders had only come down at their base in Okinawa on the day before, shaking them out of the stupor from a weekend of sex and drinking. Within a twenty-four-hour period, they went from relaxation, fun and games to a war zone.

Just a few weeks after the arrival of these Marines, in the spring of 1965, Larry Burrows, a feature journalist for Life Magazine, would write:

“The Vietcong dug in along the tree line were just waiting for us to come into the landing zone. We were all like sitting ducks and their raking crossfire was murderous. Over the intercom system one pilot radioed Colonel Ewers, who was in the lead ship: ‘Colonel! We’re being hit.’ Back came the reply: ‘We’re all being hit. If your plane is flyable, press on'”.

From that point on, thousands upon thousands would follow, with America eventually bearing witness to the deaths of approximately 58,220 U.S. Armed Forces personnel. Somewhere around 2.7 million U.S. Armed Forces members served in South Vietnam over the duration of the Vietnam War.

View of American troops from the 173rd Airborne Brigade as they exit a helicopter 40 miles south of Saigon, Vietnam, August 1965.

Fighting the Vietnam was a righteous cause. America simply made the mistake of allowing it to be conducted by know-nothing political pundits on the few television stations of the day, rather than disregarding the communist-inspired, communist funded radicals protesting in the streets and actually taking the lead from the South Vietnamese and fighting to win. But General William Westmoreland chose to use the U.S. Army to support the Army of the Republic of Vietnam [ARVN – army of South Vietnamese regulars] and fight a war of attrition, that benefited the North Vietnamese in the long term.

And, from the battle of Dak To to the siege of Saigon, Americans were inundated by the horrific images of this war every single day, like an ongoing television diary of sorts. While this was, in fact, a just war, it still seemed to shatter the dignity of all who would ultimately become involved in its execution, largely due to the barrage of anti-war propaganda that the American people had shoved in their faces each day.

The United States had been involved in military operations in Vietnam for over seven years, by the beginning of 1968, and our Armed Forces had been in major ground combat for nearly three years at that point. In country, the U.S. Amed Forces strength was 485,000 strong, and General William C. Westmoreland had been using his soldiers aggressively and quite effectively in all parts of South Vietnam to pursue the various contingents of the Viet Cong and the communist People’s Army of Vietnam [PAVN] to shield the South Vietnamese people from enemy attacks. According to the Military Assistance Command/ Vietnam [MACV], in 1967, Westmoreland’s efforts resulted in the deaths of 81,000 communist soldiers, giving substance to Westmoreland’s contention that the U.S. and its South Vietnamese allies were slowly winning the war in Vietnam.

General William Westmoreland talks with troops of first battalion, 16th regiment of 2nd brigade of U.S. First Division at their positions near Bien Hoa in Vietnam, in 1965.

The Top Brass deemed two-thirds of South Vietnam’s towns and villages were secure and under the control of South Vietnam’s government by the end of 1967, which was a stark change from 1965 when it was being chased from the countryside and on the verge of collapse. And in the meantime, communist PAVN troop strength in the South had dropped by twenty-five percent to 220,000, the result of U.S. and South Vietnamese wins on the battlefield and a decline in infiltration from the North and successful recruitment of any South Vietnamese.

However, sixteen thousand Americans had been killed in action in Vietnam by the end of 1967, and the weekly average was well above 150 per week. McGeorge Bundy, President John F. Kennedy’s former National Security Advisor, told President Lyndon Johnson:

“I think people are getting fed up with the endlessness of the fighting. What really hurts, then, is not the arguments of the doves, but the cost of the war in lives and the money, coupled with the lack of light at the end of the tunnel.”

General Westmoreland attempted to put a positive spin on the war’s progress in November 1967, when he returned to Washington, D.C. for consultations and basically asserted to Congress and the press that he believed the war was to the point “when the end begins to come into view”, as he had visions of victory swimming in his head. Little did he or anyone else know what was to come, while similar expressions of confidence emanated from the Johnson administration, as everyone simply chose to ignore all the signs that would have warned them, such as new enemy movements and the consolidation of forces and a large increase in terrorist attacks and bombings in the cities, refusing to kill Saigon’s and Washington’s joy and optimism.

The American public was taking those assessments of the situation as accurate, honest and true, and the people were temporarily mollified, until the North Vietnamese communists launched their major offensive at the end of January 1968, the Tet Offensive, which was most assuredly the point where public opinion largely started going against the Vietnam War.

Military contingents of three North Vietnamese divisions had gathered near the Marine base at Khe Sanh, which did raise initial warning bells in the Military Assistance Command, as they looked for a major offensive in the northern provinces. Some analysts of the day saw a resemblance between the situation at Khe Sanh and that of Dien Bien Phu under the French, when they were defeated by the Viet Minh in 1954. The communists put intense pressure on Khe Sanh, as eighty-four thousand communist Viet Cong and PAVN troops prepared for the Tet Offensive. They had been infiltrating arms, ammunition and men, entire units, into Saigon and many other cities and towns since September of 1967, and they managed to do so, even though the MACV had received advanced warnings of a major enemy attack scheduled for early 1968. But Westmoreland did get nervous enough to move thirteen battalions closer to Saigon before the attack, nearly doubling the U.S. military strength around the capital.

And still the U.S. and South Vietnamese appeared to get caught with their pants down, because everyone was too focused on Khe Sanh alone and the Tet holiday festivities. Even when the Viet Cong communists attacked Da Nang, Kontum, and Qui Nhon and other towns in the central and norther provinces on January 30th 1968, U.S. forces were unprepared for what followed. On January 31st the entire country was engulfed in raging combat, as 36 of 44 provincial capitals and 64 of 242 district towns were attacked, along with five of South Vietnam’s six autonomous cities, among them Hue and Saigon. Eventually, the U.S. and South Vietnamese were able to crush the attacks, but during those few days, the battles waged were some of the most bloody and violent ever seen in the South or experienced by most of the South Vietnamese Army units.

The fighting became so fierce and intense that all the U.S. Army units in the vicinity of Saigon were needed to repel the Viet Cong attacks there and at the bases of Long Binh and Bien Hoa, as even radiomen, cooks and clerks took up arms in some of the U.S. compounds in their own defense. The 716th Military Police Battalion had all it could do to ferret out the Viet Cong infiltrators from downtown Saigon and Army helicopter gunships were in the air on a continuous rotation, to assist all our forces on the ground, while the 25th Infantry Division raced their armored calvary through the night to defeat an enemy regiment that was threatening to overrun and take Tan Son Nhut Airport, one of the largest installations in the country.

Fierce, bloody battles were seen south of Saigon where the 2nd Brigade/9th Infantry Division fought in victorious fashion at Vinh Long, Cai Lay and My Tho, breaking the enemy attack in the upper Mekong Delta, and combined U.S. and South Vietnamese forces in the western highlands town of Pleiku held off a continuous Viet Cong assault for a week; but the Viet Cong very nearly cut off the supply line at a critical stretch of Highway 1 that ran from Da Nang to Phu Bai and on to Hue. It took virtually everything the Marines, 1st Calvary and 101st Airborne Divisions and the South Vietnamese 1st Infantry Division had to retake and hold Hue in the most incredibly intense and fierce combat of the war.

North Vietnamese leaders had hoped that their assault on Hue would initiate a general uprising and increase their political clout in the area, due to the Buddhist monks of the area who were activists and either neutral or espousing a separatist philosophy along with anti-American sentiments, which saw many monks of the day self-immolate in protest during those trying political times. Nearly seven entire North Vietnamese regiments were thrown at Hue, and it is one of the only instances of urban warfare during this war, as the battle was fought street to street and house to house, illustrating that the stakes at Hue were higher than anywhere else at the time, taking U.S. forces three weeks to retake after it fell to the enemy.

On June 11th 1963, Vietnamese Mahayana Buddhist monk Thích Quang Duc burned himself to death at a busy intersection in Saigon, to protest alleged persecution of Buddhists by the South Vietnamese government. President Ngo Dình Diem, part of the Catholic minority, had adopted policies that discriminated against Buddhists and gave high favor to Catholics. No news picture in history has generated so much emotion around the world as this one.

The Tet Offensive actually solidified South Vietnamese civilian support for their government instead of weakening it, especially after it became known that the Viet Cong communists had executed over four thousand civilians at Hue. Rather than grudgingly tolerating the Viet Cong, as they had in the past, they finally joined together in an active resistance, but unfortunately, even though the Viet Cong had suffered a major defeat during Tet with the loss of thousands of soldiers and political cadre, too many Americans back home in the States saw it in a much different light, that suggested the war was far from won and far from over, especially when they saw the dramatic photographs and video of the Viet Cong storming the U.S. Embassy grounds in the heart of Saigon and the North Vietnamese Army clinging tenaciously to Hue.

U.S. Marines battle North Vietnamese snipers at Hue in February 1968

Refugees flee across a damaged bridge near Hue, Vietnam. Marines intended to conduct a counterattack from the southern side, right into the citadel of the city, however, despite many guards, the Viet Cong were able to blow up the bridge. [credit, Philip Griffiths]

For the first time in our history, Americans were seeing real time images of a war flash across their television sets that were pretty much uncensored. They saw soldiers and Marines navigating through the jungles and rice paddies, trying to avoid punji sticks and anti-personnel mines, villagers huddled in fear, bombs and napalm raining down from B-52 bombers, and the gory, bloody photos of the wounded and dead on both sides. It all seemed to contradict every piece of “good news” that any official from Washington, D.C. released for public consumption.

Being an Army Brat, I grew up knowing many fine men who believed in the mission in Vietnam. I also heard many stories of many fine men who volunteered for the mission and never made it back alive, while others returned home with a chest full of medals. I was around eleven years old in the summer of 1968, when my father awakened me one night to come downstairs to meet the first soldier to receive the Medal of Honor for his conduct under fire at Camp Nam Dong on June 6th 1964 during the Vietnam War, Captain Roger H.C. Donlon. I grew up having the utmost respect for these men.

I was also troubled to see so many running off to Canada and dodging the draft, because they were either flat out cowards or sincere conscientious objectors or simply took the attitude that it wasn’t their fight or America’s and they weren’t going to be a part of it. For the true conscientious objectors, I can understand, but I still hold them in contempt for not staying and defending their position, just as Alvin C. York did during the First World War. At the time, famous boxer Cassius Clay was one who said it wasn’t his fight, more specifically, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong”, but at least he stayed and faced the consequences of his position, serving two years in prison, and I can respect such a man, even if I believe he chose the wrong path for any particular reason.

Closure…

Jeffrey Bennett – ‘Nam 1968

“Volunteered? What the hell for Bennett? Didn’t you know that you were putting your life in the line of fire?” Well – I guess that I was too naive to have given that a second thought, but I recall that while stationed in Germany, I had had an opportunity to participate in a one day mission in a helicopter (for flight pay) – and fell in love with this form of flying. Of course – the circumstances were considerably different – or so I was to discover.

The editor of the Federal Observer, Jeffrey Bennett, chose to serve during the Vietnam War. In his article, ‘‘In the Garden of Eden – a Tribute… and Thanks‘ [October 1, 2017], he saves the following for the sake of history and in part notes:

June 6, 1968: … and so my journey with the 498th Dust Off Company began. Within days I volunteered along with Dave Banks as a crew-member of one of the most elite Med Evac Units in-country. Reading books years later I was surprised at the reverence paid by other groups of our type to our group.

April 30, 2025

Justin O. Smith ~ Author

~ The Author ~

Justin O. Smith has lived in Tennessee off and on most of his adult life, and graduated from Middle Tennessee State University in 1980, with a B.S. and a double major in International Relations and Cultural Geography – minors in Military Science and English, for what its worth. His real education started from that point on. Smith is a frequent contributor to the family of Kettle Moraine Publications.