The Trump administration’s hard-line stance on keeping migrants out is pushing asylum seekers to take remote and dangerous routes into the United States. And a wall might not be able to fix that.

The number of migrant families crossing the southwest border has once again broken records, with unauthorized entries nearly doubling what they were a year ago, suggesting that the Trump administration’s aggressive policies have not discouraged new migration to the United States.

The number of migrant families crossing the southwest border has once again broken records, with unauthorized entries nearly doubling what they were a year ago, suggesting that the Trump administration’s aggressive policies have not discouraged new migration to the United States.

More than 76,000 migrants crossed the border without authorization in February, an 11-year high and a strong sign that stepped-up prosecutions, new controls on asylum and harsher detention policies have not reversed what remains a powerful lure for thousands of families fleeing violence and poverty.

“The system is well beyond capacity, and remains at the breaking point,” Kevin K. McAleenan, commissioner of Customs and Border Protection, told reporters in announcing the new data on Tuesday.

The nation’s top border enforcement officer painted a picture of processing centers filled to capacity, border agents struggling to meet medical needs and thousands of exhausted members of migrant families crammed into a detention system that was not built to house them — all while newcomers continue to arrive, sometimes by the busload, at the rate of 2,200 a day.

“This is clearly both a border security and a humanitarian crisis,” Mr. McAleenan said.

[Read the latest edition of Crossing the Border, a limited-run newsletter about life where the United States and Mexico meet. Sign up here to receive the next issue in your inbox.]

President Trump has used the escalating numbers to justify his plan to build an expanded wall along the 1,900-mile border with Mexico. But a wall would do little to slow migration, most immigration analysts say. While the exact numbers are not known, many of those apprehended along the southern border, including the thousands who present themselves at legal ports of entry, surrender voluntarily to Border Patrol agents and eventually submit legal asylum claims.

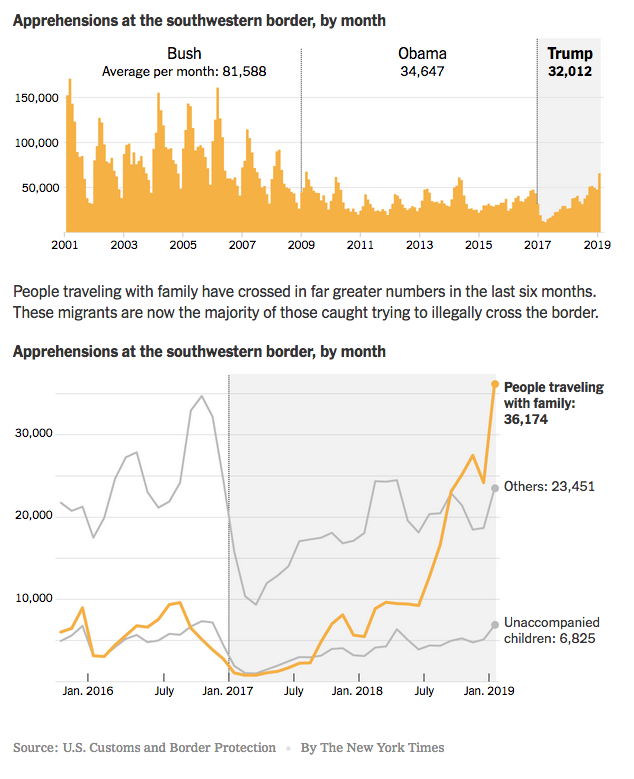

Illegal Border Crossings Have Spiked in Recent Months

Over the past two decades, there were large declines in apprehensions along the southwestern border with Mexico. Despite the overall trend, illegal border crossings have surged in the current fiscal year, which began in October.

The main problem is not one of uncontrolled masses scaling the fences, but a humanitarian challenge created as thousands of migrant families surge into remote areas where the administration has so far failed to devote sufficient resources to care for them, as is required under the law.

The main problem is not one of uncontrolled masses scaling the fences, but a humanitarian challenge created as thousands of migrant families surge into remote areas where the administration has so far failed to devote sufficient resources to care for them, as is required under the law.

The latest numbers stung an administration that has over the past two years introduced a rash of aggressive policies intended to deter migrants from journeying to the United States, including separating families, limiting entries at official ports and requiring some asylum seekers to wait in Mexico through the duration of their immigration cases.

More than 50,000 adults are currently in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody, the highest number ever.

Despite targeted successes in certain areas — about 2,000 migrants who traveled in a caravan from Central America last year appeared to have given up their cause as of last month after being discouraged by long delays in Tijuana — migrants seem only to have adjusted their routes rather than turn back. Indeed, they are traveling in even larger numbers than before.

Arrests along the southern border have increased 97 percent since last year, the Border Patrol said, with a 434 percent increase in the El Paso sector, which covers the state of New Mexico and the two westernmost counties of Texas. Families, mainly from Central America, continue to arrive in ever-larger groups in remote parts of the southwest.

At least 70 such groups of 100 or more people have turned themselves in at Border Patrol stations that typically are staffed by only a handful of agents, often hours away from civilization. By comparison, only 13 such groups arrived in the last fiscal year, and two in the year before.

Understanding what is happening on the border is difficult because, while the numbers are currently higher than they have been in several years, they are nowhere near the historic levels of migration seen across the southwest border. Arrests for illegally crossing the border reached up to 1.64 million in 2000, under President Clinton. In the 2018 fiscal year, they reached 396,579. For the first five months of the current fiscal year, 268,044 have been apprehended.

Migrants from Central America turned themselves in to Border Patrol agents in Penitas, Tex., last month.CreditTamir Kalifa for The New York Times

The difference is that the nature of immigration has changed, and the demographics of those arriving now are proving more taxing for border officials to accommodate. Most of those entering the country in earlier years were single men, most of them from Mexico, coming to look for work. If they were arrested, they could quickly be deported.

Now, the majority of border crossers are not single men but families — fathers from Honduras with adolescent boys they are pulling away from gang violence, mothers with toddlers from Guatemala whose farms have been lost to drought. Most of these migrants may not have a good case to remain in the United States permanently, but because of legal constraints, it is not so easy to speedily deport them if they arrive with children and claim protection under the asylum laws.

Families with children can be held in detention for no longer than 20 days, under a much-debated court ruling, and since there are a limited number of detention centers certified to hold families, the practical effect is that most families are released into the country to await their hearings in immigration court. The courts are so backlogged that it could take months or years for cases to be decided. Some people never show up for court at all.

Finally, detaining families even for the first few days after their arrival in the United States, while they are undergoing initial processing, is also a challenging job.

Often arriving exhausted, dehydrated, and some of them requiring urgent medical care, the families need food, diapers, infant formula and space to play. They often spend days inside cramped concrete cells that were built to house the previous generation of border crossers — young, single men who would likely be there only a few hours.

As part of the announcements on Tuesday, Mr. McAleenan also said the agency is making sweeping changes to procedures for guaranteeing adequate medical care for migrants — an overhaul brought on by the deaths of two migrant children in the agency’s custody in December. The measures, which include comprehensive health screenings for all migrant children and a new processing center in El Paso that would help provide better shelter and medical care for migrant families, are an attempt to fix years of health care inadequacies that have left many at risk.

As part of the announcements on Tuesday, Mr. McAleenan also said the agency is making sweeping changes to procedures for guaranteeing adequate medical care for migrants — an overhaul brought on by the deaths of two migrant children in the agency’s custody in December. The measures, which include comprehensive health screenings for all migrant children and a new processing center in El Paso that would help provide better shelter and medical care for migrant families, are an attempt to fix years of health care inadequacies that have left many at risk.

The agency will also expand medical contracts to place health care practitioners — largely registered nurses and nurse practitioners — in “high-risk” and high-traffic locations along the border. It will also dedicate more money for translation services to meet increasing demand from Central Americans, many of whom speak indigenous dialects and may not be able to communicate their needs in English or Spanish.

“These solutions are temporary and this situation is not sustainable,” Mr. McAleenan said.

Mr. McAleenan said the authorities believe that the large numbers of families are coming because smugglers have effectively communicated across Central America that adults who travel with children will be allowed to enter and stay in the United States.

Brian Hastings, the agency’s chief of law enforcement operations, said that since April 2018, border agents had detected nearly 2,400 cases in which migrants had falsely claimed to be related when they were not, or untruthfully claimed to be younger than 18.

The throngs of new families are also affecting communities on the American side of the border. In El Paso, a volunteer network that temporarily houses the migrants after they are released from custody has had to expand to 20 facilities, compared with only three during the same period last year. Migrants are now being housed in churches, a converted nursing home and about 125 hotel rooms that are being paid for with donations.

“We had never seen these kinds of numbers,” said Ruben Garcia, the director of the organization, called Annunciation House. He said that during one week in February, immigration authorities had released more than 3,600 migrants to his organization, the highest number in any single week since the group’s founding in 1978.

For the most part, Mr. Garcia said that his staff and volunteer workers had been able to keep up with the surge, often making frantic calls to churches to request access to more space for housing families on short notice. But sometimes their best efforts were upended, he said, including on one day last week, when the authorities dropped off 150 more migrants than planned.

“We just didn’t have the space,” Mr. Garcia said.

Written by Caitlin Dickerson and published by The New York Times ~ March 5, 2019.