More than 3,000 resettled since pandemic task force was created

Silhouettes of refugees people searching new homes or life due to persecution. Vector illustration

Following the alarming spread of the Coronavirus or COVID-19 that appeared in China in December 2019, the world is taking extreme measures to try and contain this contagious virus that is mainly transmitted from person to person. Necessary steps undertaken by many countries, including the United States, entail travel restrictions, quarantines, closing of borders, etc.

Despite tough measures undertaken by the Trump administration these past weeks to limit the virus outbreak inside the United States, refugees are still being admitted into American communities. From January 29 (the day the president’s Coronavirus Task Force to lead the U.S. government response to the coronavirus was formed) to March 18 (the deadline I used for this report), the United States resettled 3,037 refugees, including 19 Iranians (Iran is one of the countries particularly affected by the coronavirus). Before I sent this piece for publication, I checked again for admissions: On March 19, two Syrian refugees were admitted into the United States. Both were placed in New Jersey, in the city of Highland Park. These could be the last refugees to be resettled into the United States amid the coronavirus pandemic.

But that doesn’t answer the following: Why were these thousands of refugees allowed in when, by the admission of both chiefs of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, “refugees may be particularly targeted” by the coronavirus?

Why were 3,037 refugees allowed in after the president’s task force was formed, or after January 30, when the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a public health emergency, or after March 11, when WHO characterized the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic?

And, more importantly, were they tested for the coronavirus beforehand? I couldn’t find any indication they were anywhere. Let’s assume they were, and the results came back negative (we are told that even if one is tested negative it doesn’t mean one is not carrying the virus), were they quarantined upon arrival? Were there any follow-ups to make sure they were fine? Were governors of the states they were placed in (such as California, Washington, Texas, New York, etc.) made aware of such arrivals and risks? In view of this dramatic health crisis, state and local officials might want to reconsider their relentless commitment to the refugee resettlement program, and finally take advantage of the opportunity given to them by President Trump to have a say in the number of refugees placed into their communities.

Nationalities and Processing Countries

The top-10 countries of origin for the refugees resettled from January 29, 2020 to March 18, 2020 are as follows (figures gathered from the U.S. Refugee Processing Center portal): Democratic Republic of Congo, 1,022; Ukraine, 580; Burma, 249; Afghanistan, 214; Iraq, 154; Russia, 138; Sudan, 91; Colombia, 78; Pakistan, 63; and Syria, 66.

Nineteen nationals from Iran were also resettled during this period, a country particularly affected by COVID-19.

On February 29, President Trump expanded on an existing ban on travel from Iran in response to the coronavirus outbreak, stopping any foreign national who has visited that country within the last 14 days from entering the United States. Yet Iranian refugees and others from regions of turmoil and insecurity are still being admitted.

It is true that refugees being resettled are usually processed in their countries of first asylum and not in their home countries, but refugees are known to seek refuge in countries neighboring their own.

The top-10 processing countries of refugees admitted in the United States from October 1, 2019, through February 29, 2020 (the only data available on the Refugee Processing Center portal for that period) were: Ukraine, 1,307 refugees; Malaysia, 606; Turkey, 493; Rwanda, 379; Thailand, 374; Tanzania, 372; Burundi, 331; Moldova, 280; Uganda, 195; and Ethiopia, 168.

Also, it is hard to determine when these refugees were in their home country last or whether or not they came into contact with any of their compatriots who were. As the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees underlined recently: “If ever we needed reminding that we live in an interconnected world, the novel coronavirus has brought that home. … People on the move, including refugees, may be particularly targeted.” (Emphasis added.) Speaking to NBC News on March 19, aid agencies warned of the risks a coronavirus outbreak poses to “refugees around the world who often live in cramped conditions, lack access to clean water and are in countries with failing or stretched medical systems.” (Emphasis added.) Humanitarian workers concluded: “[I]n the absence of extensive testing at refugee camps in the Middle East, Africa or Asia, it’s unclear whether the fast-moving virus has already reached them.” (Emphasis added.)

Yet, refugees who could be “particularly targeted”, according to refugee experts, were still being placed in American communities.

State Placement and State and Local Involvement (or Lack Thereof)

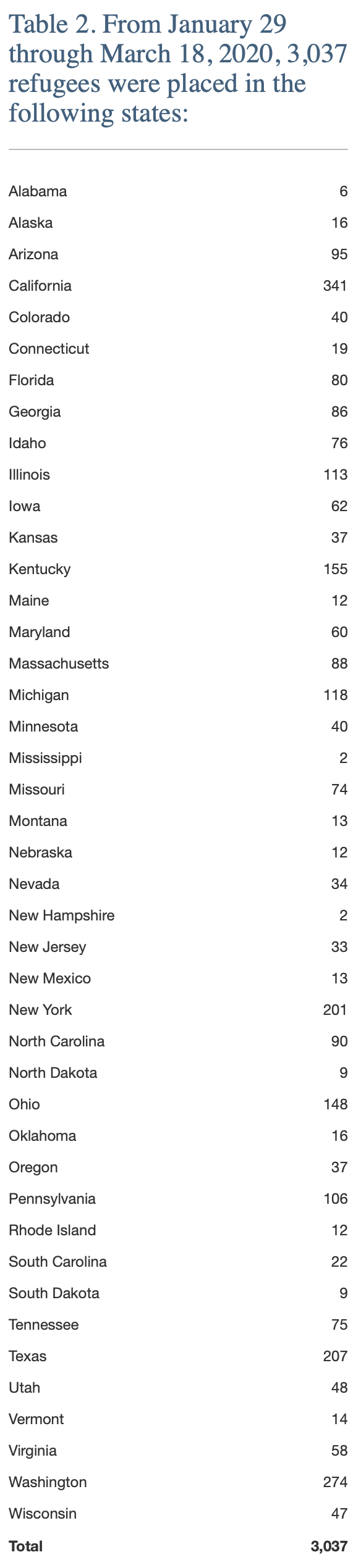

The top-10 states where refugees were resettled from January 29, 2020 to March 18, 2020, according to the official U.S. government Refugee Processing Center portal are as follows: California, 341; Washington, 274; Texas, 207; New York, 201; Kentucky, 155; Ohio, 148; Michigan, 118; Illinois, 113; Pennsylvania, 106; and Arizona, 95.

See Table 2 for a detailed placement count by state. It is important, in view of the exceptional health hazards, to know exactly who was resettled where.

This might give state governors and local officials food for thought. Despite President Trump’s Executive Order on Enhancing State and Local Involvement in Refugee Resettlement giving state and local governments the possibility to opt out of the refugee resettlement program altogether (which was later blocked by a Maryland judge), a large number of governors (including Republicans) expressed their commitment to resettling refugees in their communities. Only Governor Greg Abbott of Texas announced that his state would not be participating in the refugee resettlement program in FY 2020 (207 refugees were resettled in Texas from January 29 through March 18). State governors encouraged by lower admission numbers (FY 2020 ceiling of 18,000 is down from the FY 2019 ceiling of 30,000) possibly thought it did not really matter. As my colleague Mark Krikorian noted in January, “Because there are so few new refugees being admitted, it’s a lot less politically risky to agree to take them.” But as we are sadly learning today, it’s not about the numbers — one person could suffice for the virus to spread.

Refugee Resettlement Program Suspended too Late?

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, and IOM, the International Organization for Migration, announced on March 17, the temporary suspension of resettlement travel for refugees in view of the COVID-19 global health crisis. IOM and UNHCR explained the suspension were to “begin to take effect within the next few days as the two agencies attempt to bring those refugees who have already cleared all formalities to their intended destinations.”

The U.S. refugee resettlement program might be finally shutting down — the two Syrian refugees admitted on March 19 might be the last ones resettled for a while. But at what cost?

While the president, state governors, and health care experts are shutting U.S. borders and asking Americans to stay home, restrict their travels, close their businesses, restaurants, bars, and schools, and even refrain from visiting their elderly — all this at enormous emotional and financial cost — refugees from high-risk areas are being admitted into their communities. Why?

The responsible thing to do now is follow up with each and every refugee who was resettled during that period to make sure they, and the communities they were welcomed into, are and remain safe and healthy.

Governors and local officials need to make sure of that.

Written by Nayla Rush for Center for Immigration Studies ~ March 20, 2020