NOTE: The following was originally re-published by Kettle Moraine Publications in late June of 2018, however during our purge of the site, this column was accidentally lost. We are excited to have found it once more. For those of my Brothers and Sisters who walked (or flew) in my boots… I’ll see you at Sundown. ~ JB

A young US Marine Corps corporal directs modern history’s largest Naval bombardment in support of ground forces, wiping out an entire Viet Cong battalion augmented by Red Chinese regular soldiers.*

28-29 July 1965

Where the hell are you, Charlie? You’re out there. I feel it.

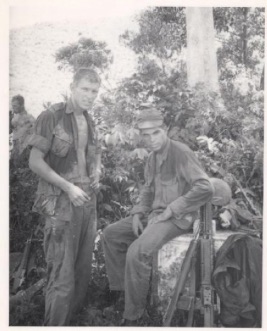

Corporal Karl Lippard (left) and Lance Corporal Arturo Nunez, one of Lippard’s machine gun team members.

A rawboned, lanky U.S. Marine strained to detect movement in the inky darkness, a starless space made blacker by a rain squall that suppressed the sounds of soldiers creeping toward their objective. A few feet away, a South Vietnamese Ranger, Sergeant Thi, also patrolled, straining to spot a large Viet Cong force they knew was approaching. An attack was imminent.

As he scouted the area, Corporal Karl Lippard mentally took inventory of his dicey situation and limited assets. He was armed with an M14 rifle and four 20-round magazines. Sgt. Thi carried a .30-caliber M1 carbine, and a Colt 1911 semiautomatic pistol was tucked in his M9 shoulder holster. The Marine had stowed his map case, helmet, poncho and pack in an old French bunker near the Ca De River bridge’s north approach. A telephone land line linked the abandoned bunker to roughly 20 other Marines dug-in on the south side. All were “Raiders”, a company of U.S. Marines that had received specialized training—“rubber boat” operations and submarine insertion, for example. Raiders were elite forces, the handpicked best of each U. S. Marine Corps battalion.

As the rain squall intensified, Lippard and Thi returned to the French bunker to retrieve their ponchos. A South Vietnamese army (ARVN) soldier was manning the concrete shelter, talking on a PRC-10 backpack radio…but to Viet Cong troops. Lippard pulled the pin on a grenade and placed a hand on the bunker wall, but before he could take out the VC infiltrator, Sgt. Thi tossed his own grenade. Its blast cut the enemy soldier in half, severed the phone line and drove debris into Lippard’s knee.

“My grenade was live, still in my hand, when I got hit,” Lippard recalled. “Had to replace the pin.” The Marine stepped inside the bunker, confirmed the VC was a goner and checked the PRC-10 radio. It was covered in blood and raw flesh, but still functional.

That radio would become his lifeline.

Positioned on the north side of the Ca De River, which emptied into nearby Bay of DaNang, Lippard was acutely aware that he and his Vietnamese Ranger sidekick were mere tripwires, a flesh-and-blood early warning system. The 19-year-old Marine had orders to sound a warning, if anybody approached the bridge from the north. Nobody—friend or foe—would be permitted to cross.

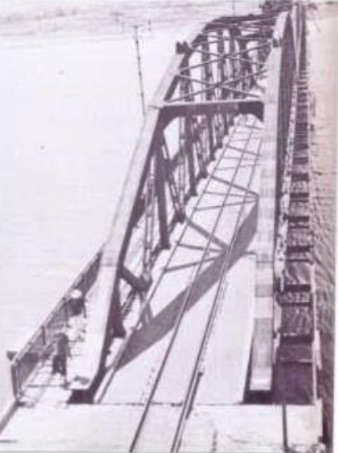

Ca De River Bridge

Had the VC mole alerted nearby enemy troops that the bridge was defended by a pitifully small force? No way of knowing, but the grenade blast that had silenced him surely would attract Charlie’s attention to the old bunker.

In fact, Lippard wasn’t “officially” in that bunker on the Ca De River’s north bank. Then-Major General Lewis W. Walt’s Tactical Area of Responsibility ended on the south end of a five-span, quarter-mile steel structure. With a set of railroad tracks down the center and pedestrian walkway along the west side, the bridge was a critical north-south artery. “Highway One” and a railroad converged at that crossing, a gateway to the main route linking “DaNang to places north, such as Phu Bai and Hue,” according to the record of a ship soon to be anchored nearby, in the bay.

Holding that junction was absolutely vital. Regimental commander Colonel Edwin B. Wheeler had told 2nd. Lt. James Reeder, Lippard’s immediate commander, “Lieutenant, if you lose this bridge, you and I are both going to be fired.” But holding it from only the south end was tactically near-impossible.

“There was no room to support Marines on the south side,” Lippard recalls. “The available space [there] could only hold about 20 Marines. Besides, that’s about all that could be spared. We were spread real thin in July 1965.”

To have any serious hope of preventing enemy troops from taking the bridge, a full company of Marines, backed by artillery, should have been firmly entrenched on the north side. But bizarre rules of engagement in mid-1965 placed responsibility for defending that important span’s northerly approach in the hands of a South Vietnamese army battalion located about a half mile farther north, close to the beach. Comprising two understrength platoons, these“Popular Force” troops were a battalion in name only, a reserve unit commanded by a schoolteacher. They were volunteers, designated the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) 2nd Regional Force.

A USMC battalion would be composed of 1,000 Marines. In contrast, “a Vietnamese ‘battalion’ would indicate 600 or more men,” Lippard explained. “Years later, we found documents [proving] the ARVN 2nd was only a couple of platoons, mostly farmers. Weekend warriors, often with families in tow. But two platoons of drop-and-run farmers wouldn’t cut it, if hit. That ‘battalion’ would be wiped out.”

Lippard and Thi knew little about Viet Cong movements in the area or the unit set to attack the bridge that night. They had been given no intelligence, even though 3rd Marine headquarters was well aware that the 7th Viet Cong Battalion had slipped between the Bay of DaNang and a ridge of mountains the day before. Two Marine companies had been dispatched to engage that force, but they never encountered the 7th VC. It had already passed through, pushing to the north.

Records indicate that Navy ships positioned offshore had “tried to interdict this battalion, shelling its [potential] positions, as it moved,” Lippard said. A combat action report noted the 7th VC was still on the march 28 July, arriving in a valley a few miles north of the Ca De River bridge late that day.

Well after sunset, two separate formations, each comprising two companies of Viet Cong and Red Chinese regulars, started maneuvering to the south. Their apparent plan was to sweep across the Ca De River bridge, overrun a 3rd Marine Division command post and capture the huge DaNang airbase 4.5 miles west of the city.

“Confirmed,” Lippard asserted. “There were [a total of] 16,516 Viet Cong against 1,140 men of 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, in open, fixed positions. They’d be overwhelmed, with no support,” if squeezed by enemy troops from the north and south.The enemy would have destroyed innumerable aircraft, including helicopters slated to support a major battle shaping up at Chu Lai, well to the south.

“The Fourth Marines would have been doomed,” Lippard declared. “Another 1,121 Marines—the First of the Fourth—on the beach to the northeast at Ky Ha would have been next. General Walt could see it coming. His [planned] strike at Chu Lai…would be preempted by that VC offensive [launched] at the Ca De River bridge. He had no real protection. No one to come to his aid. Therefore, he sent what he had to the bridge and hoped for the best.”

Conceivably, the 7th VC—about 600 strong—would race down to Chu Lai, attacking from behind and wiping out an assembling American force of some 1,140 men.

The only speed bumps were a Marine and ARVN Ranger holed up near a bunker on the north end of the bridge, backed by 20 lightly armed Marines on the south side. It’s safe to assume that 7th VC commanders fully expected to swat that handful of Marines aside and be in control of DaNang air base before dawn on 29 July.

Clearly, U.S. commanders were anticipating an attack from the northwest by a massive VC force estimated to total 5,574 combatants in the DaNang operations area. On 1 July, Marine Division headquarters had issued an order warning of precisely that possibility. A subsequent missive on 17 July approved naval gunfire support (NGS) for in-country employment, albeit with constraints. Supporting fire had to be “observed and controlled,” called in by only U.S. forces, and independent fire from any ship offshore was banned.

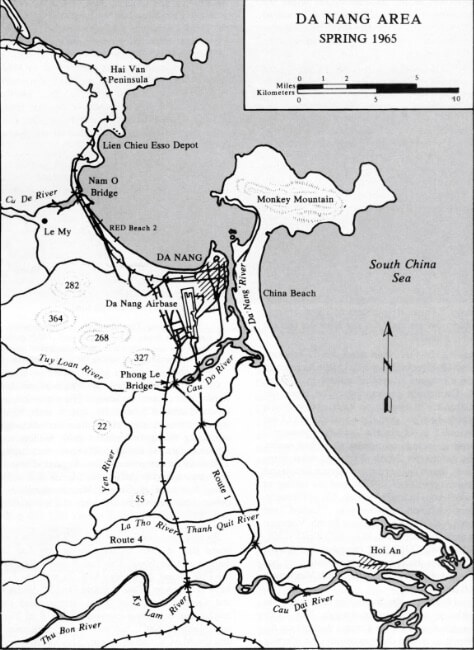

DaNang operations area. Battle of the Ca De River bridge occurred in the upper left.

Something big was about to happen, but Lippard had no idea what. Around 2100 (9:00 p.m. local), “we began to receive enemy fire from several directions [near] the bunker, increasing in intensity as I tried to raise somebody on the radio,” he said. Only one faint response was received—a patrol some five miles up-river. It was unable to relay a message.

“A Mayday call went out to any station on the net, “Lippard recounted.“Division headquarters came up, and I quickly gave them positions of attacking forces, while I could.” He noted that the enemy was “Danger close!” No artillery was available, so aircraft were dispatched. Soon, USMC F-4B Phantoms from DaNang air base arrived and made three strikes on coordinates Lippard provided, pounding rear elements of the 7th VC Battalion.

“Division never identified themselves. Never said what, if anything, they were sending,” Lippard said. He was told to identify himself, “but I declined to give my position. Evidently satisfied, they sent everything they had—aircraft and ships.” One U.S. Navy ship steamed for several hours to get on-station. “So division knew they were in trouble. They also knew somebody on the other end of that radio [link] could read a map and was under fire. A heavy firefight was in progress.”

Seasoned enemy soldiers intent on clearing the French bunker and sprinting across the bridge were hardly deterred by three rapid-fire F-4 strikes. The 7th’s troops kept coming, and Lippard and Sgt. Thi kept picking them off, when briefly illuminated by lightning.

In short order, Lippard had shot and killed 15-20 enemy soldiers with his M14. “They were attacking in threes, so we could take them down fairly quickly.” Sgt. Thi ran out of M1 ammunition, prompting Lippard to trade his M14 and extra ammo magazines for Thi’s .45-caliber pistol. The Marine could fire the forty-five one-handed and still operate the PRC-10 radio, his only means of communication.

Fortuitously, Lippard happened to be an expert shot with a forty-five. Years later, he would set world records for nailing targets at 500, 600 and 1,000 yards with the “Combat NCO”, a .45-caliber semiautomatic of his own design.

With enemy fire zeroed-in on the old bunker, Lippard and Thi abandoned it, moved about 75 yards up the beach, and took cover behind sand dunes, backs to the water. Lippard radioed a brief situation report (SITREP) to division headquarters, which merely acknowledged that artillery couldn’t reach him, then went silent.

“No further transmission. None from them or me. I was busy,” Lippard clipped. The young Marine was on his own. Reinforcements and artillery simply weren’t available. He transmitted in the blind, “”Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! Any station this net! This is Hotel Three! Do you copy? Over!”

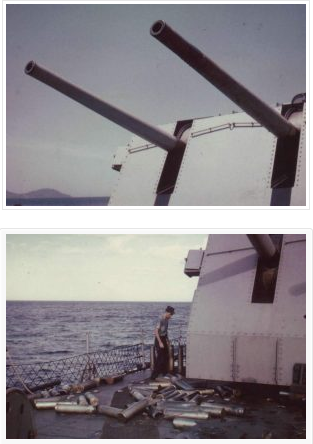

USS John R. Craig (DD-885)

“Hotel Three, this is Assassin. Give me your coordinates.” Out there in the DaNang Bay, just offshore, a very powerful ally was arriving. Answering Lippard’s call was Harry Rodgers RD2, a sailor aboard the USS John R. Craig (DD-885), a U.S. Navy destroyer sporting four five-inch guns, two on its forward deck and another two on the aft. Rodgers was tasked with maintaining communications between the ship and a “target spotter” ashore. He received and plotted target coordinates as requested by the spotter. Those were passed to the ship Gunnery Officer, who fed them into a fire control computer and fired the guns. The spotter—Lippard, in this case—would call for illumination, high-explosive or white phosphorus rounds and make target adjustments, as required.

Navy gun support tactics in mid-1965 were to “get in as close to shore as possible, drop anchor and maneuver [to] bring guns to bear, while swinging on the anchor chain,” according to the Craig’s history. The ship drew about 18 feet of water and was now anchored in about 25 feet. Crewmembers said the Craig’s propellers were churning up bottom mud to keep the ship broadside to the beach, ensuring both fore and aft five-inch gun mounts could provide supporting fire.

By 2141 (9:41 p.m. local), the Craig was in position, lights out, and starting to fire illumination rounds, directed by Lippard’s radio calls. Now, “I could see the [enemy] force…but was unaware that a whole battalion was engaging,” the Marine recalls. “The Craig came in [and started firing] to the right of the airstrikes, immediately across my front, giving me some relief.”

Once he realized a huge Viet Cong/Red Chinese force was caught in the open, lit up by the Craig’s first illumination rounds, Lippard requested high-explosive shells. “I called the first rounds within 100 yards” of his and Thi’s beach position. “If I had not retired to the beach, I would have died at the bridge. It was very bad on the beach, but the dunes [absorbed] a lot, and as the enemy fell back, concussions from naval gunfire and [incoming] enemy fire decreased.”

Noise from airbursts was deafening, complicating radio communications. As Lippard shot enemy soldiers closing on his position, he transmitted a steady stream of radio calls, directing the big guns’ devastating fire. High explosive rounds “were tight” and accurate. The advantages of heavy rain and pitch darkness that enemy commanders had counted on for concealment were eradicated by frequent illumination rounds turning night into day.

Up the beach, the South Vietnamese reserves “were digging to China, pinned against the sea. [The Craig’s incessant barrage] had them bottled up and afraid to move,” Lippard said. “They had no idea who was calling in the fire or where it was coming from.”

Illumination rounds enabled Lippard and Thi spotting and shooting enemy troops “that made it to within fifteen yards of us. It was close; very, very close,” the Marine distinctly remembers. “The ‘problem’ was danger close that night. I was down to just my pistol, and plotted the last rounds right on my position. [We] could not hold, without maximum firepower on me. We got lucky.”

Lippard was a reluctant student, when assigned to Map and Aerial Photo School in his early Marine Corps days, yet graduated at the top of his class. On the night of 28-29 July 1965, he was grateful for training-honed skills that enabled calling in absolutely devastating fire for almost five hours. The USS Craig ultimately fired 340 five-inch rounds—57 illumination, 22 white phosphorous and 261 high-explosive shells.

At 0146 (1:46 a.m.) on 29 July, the USS Stoddard (DD-566) slipped into DaNang Bay and joined the battle. Lippard was unaware that two ships were firing through the night. He simply called the coordinates and that zone was obliterated. “They answered a Marine corporal’s Mayday. No questions.”

Relentless pounding by two Navy destroyers’ five-inch guns forced the Vietcong and Red Chinese regulars to “collapse on themselves. I followed up the beach as enemy troops [dropped back], then inland as they retraced their approach of march,” Lippard continued. Approaching the ARVN reserves’ position, “Sgt. Thi broke off to identify me on their flank. I moved inland, following the enemy and [directing naval] gunfire. I was then forty-five yards forward of the ARVN position.” The Marine was alone in no-man’s land, surrounded by dead enemy soldiers…or what was left of them. Lippard doesn’t talk about that.

Relentless pounding by two Navy destroyers’ five-inch guns forced the Vietcong and Red Chinese regulars to “collapse on themselves. I followed up the beach as enemy troops [dropped back], then inland as they retraced their approach of march,” Lippard continued. Approaching the ARVN reserves’ position, “Sgt. Thi broke off to identify me on their flank. I moved inland, following the enemy and [directing naval] gunfire. I was then forty-five yards forward of the ARVN position.” The Marine was alone in no-man’s land, surrounded by dead enemy soldiers…or what was left of them. Lippard doesn’t talk about that.

When the Craig and Stoddard ceased firing, “I retired back to the beach and retraced my movements to the point of first call [for naval gunfire]. There I remained until daylight.” The Craig was ordered to weigh anchor and depart around 0310 (3:10 a.m.), but the Stoddard remained in DaNang Bay until about 10:00 a.m. “The battle was over, but she finished some mop-up, [shelling] the base of the mountains [to take out] any stragglers or other units that might arrive.”

The USS Craig’s scorched 5-inch gun barrels and expended brass.

Records of the battle are sketchy and don’t always agree, but Lippard’s research found that 443 shells were fired by the Craig and Stoddard in response to his Mayday calls the night of 28-29 July 1965. Another 33 were delivered, during post-battle mop-up operations. Ship logs have ambiguous accounts, including numbers that don’t match other records: the USS John R. Craig—under the command of Navy Commander James Kenneth Jobe and supported by Lt. Jeremy Michael Boorda, the Weapons Officer—fired 348 rounds, while “conducting a night firing mission.” How many the USS Stoddard delivered under the command of U.S. Navy Commander Charles Presgrove is believed to be 95 rounds in the early morning hours of 29 July, and another 174 in “after-action” operations, according to a Naval War Gunfire Support Record.

A personal log written by Henry Lehtola, an enlisted sailor-turned-historian who chronicled the Craig’s role in the 28-29 July 1965 battle for the Ca De Bridge backs Lippard’s account: “Anchored DaNang. …preparing to open fire. The VC must have been raising hell earlier. You could hear small arms fire on the beach and see tracers flying. Flares and star shells lit up the whole sky.”

The U.S. Marine Corps War Journal’s cursory documentation for 28 July notes, “USS Craig commenced firing on designated targets. 340 five-inch rounds expended—57 illumination; 22 white phosphorous, and 261 high explosive. At 0146 hr., Craig joined by USS Stoddard (DD-566) in support.”

Although exhausted, Corporal Karl Lippard jotted down a few notes about the night’s battle and had his knee wound dressed. Later, he snapped several color photos, then waited, fully expecting a thorough debriefing by his commanders. It didn’t happen. Nobody at headquarters ever asked for Lippard’s account, verbal or written.

Senior Marine commanders definitely knew the intense Ca De River bridge battle had occurred. In fact, the USS Craig and Stoddard destroyers would not have steamed into DaNang Bay in response to Lippard’s Mayday call, unless ordered by the Commanding General of Naval Forces, Maj. Gen. Walt. However, 3rd Marine headquarters apparently never reported the engagement’s stark truth: A single USMC Raider, aided by an ARVN Ranger, directed naval gun fire on a battalion-size unit of enemy soldiers caught in the open. After about five hours of intense bombardment, the Viet Cong 7th Battalion ceased to exist. No enemy soldiers captured. No wounded recovered. No sign that any of the unit’s approximately 600 Viet Cong and Red Chinese combatants had escaped. The 7th VC simply vanished, never to reappear in subsequent reports.

Incredibly, not a single Marine or ARVN soldier was killed. “No Marine or ARVN losses,” Lippard confirmed.

“The end result of this battle was total destruction of the 7th Viet Cong Battalion, by U.S. Marines in defense of the bridge complex,” Lippard recapped. “The Marine Corps acted with speed and force—brought in Marine Air Wing strikes and quickly moved Navy ships into position to provide full gun support within minutes of my call. …This is believed to be one of the finest examples of combined Navy and Marine assets…in support of a small unit, during the Vietnam War.”

Although U.S. commanders may have ignored or forgotten the Ca De River bridge battle, senior South Vietnamese military and political leaders deeply appreciated what Lippard and his fellow Marines had done. Lippard was quickly summoned to an ARVN headquarters and awarded the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry with Palm insignia, the first of three he earned. Later, Vietnam’s then-Premier, Nguyen Cao Ky, recognized Lippard for his distinguished actions in defending the bridge.

Why top U.S. officers never acknowledged Corporal Lippard’s role in the Ca De River bridge battle and decimation of a large enemy force in late July 1965 remains a glaring unknown. Theories abound, and there are probably bits of truth in each. Marine commanders, at that time, were convinced their communication links had been compromised. Reporting through regular channels that a major headquarters and the vital DaNang airbase came within a whisker of being overrun and wiped out by a Viet Cong force augmented by Communist (dubbed “Red” by Marines) Chinese soldiers might have alerted North Vietnamese interceptors that U.S. and ARVN forces were spread dangerously thin south of the Ca De River. Such knowledge certainly would have emboldened VC commanders to try taking the bridge again. As it was, a few days later, on 5 August, Viet Cong troops managed to blow up fuel tanks containing about 2,000,000 gallons of jet fuel near DaNang.

Or maybe acknowledging that a solitary U.S. Marine was outside the allowed operating area—north of the bridge, in ARVN territory—and calling in U.S. Navy gunfire to wipe out a large enemy force was considered too sensitive for political palates. At the time, South Vietnamese military leaders were suspicious of U.S. intentions and quick to call foul.

Had the 7th VC Battalion broken through and destroyed critical strike aircraft and helicopters on the DaNang air base flightline in late July, a key Marine attack at Chu Lai, planned for mid-August, might have been scrubbed. Nobody in the U.S. chain of command dared admit that the Marine Corps came very close to suffering one of its worst defeats in history, just as that major offensive was in the offing. Especially at a politically sensitive time, when the White House and Pentagon desperately needed a victory to establish U.S. credibility in Vietnam.

Ironically, 614 Viet Cong were killed and nine taken prisoner in the subsequent Chu Lai battle—about the same as North Vietnam lost in one night at the Ca De River bridge. And forty-five Marines were killed and 120 wounded in the week-long battle at Chu Lai. In contrast, none were lost, during a furious, five-hour shootout north of the Ca De River that night of 28-29 July.

For whatever reason, the 18-24 August 1965 battle at Chu Lai is hailed as the U.S.’s “decisive first victory” by historians, while a deadly storm of fire and steel that erased an entire Viet Cong battalion almost one month earlier is never mentioned in official and scholarly accounts of the Vietnam War. At least none have surfaced. Was it buried in official secrecy born of near-miss embarrassment? Or intentionally “overlooked” and conveniently forgotten?

For his extraordinary, central role in holding a crucial river crossing, Lippard never received a blip of public acknowledgment, word of high-rank congratulations or simple “thanks”—let alone a medal—from his own country. Not even a purple heart for a wound received in heavy combat that night.

True to Karl Lippard form, though, he doesn’t really care. Instead, he chooses to emphasize that the Ca De River battle is a testament to the historically effective American military philosophy of training its warriors to improvise on the fly and do what it takes to get the job done. The ferocious fight of 28-29 July 1965 is also a loud-and-clear example of the trust placed in every Marine “Raider”, whose call for artillery, air or naval gunfire support isn’t questioned. Those holding the lightning bolts of American power merely “Roger” and commence firing or dropping on targets the Marine designates.

In Lippard’s four-year tour as an active-duty Marine, he was wounded seven times and finally returned to the states on a gurney. He was offered a field commission to 2nd Lieutenant, but declined. Instead, he was promoted to Sergeant (E-5) and assigned to the drill field, turning fresh recruits into a new generation of Marines. Thanks to right-shoulder wounds, Lippard had the distinction of being the only Marine permitted to salute with his left hand.

He worked in the aerospace, property development and construction sectors for several years, but ultimately established himself as a world-class gunmaker and designer. He holds 20 patents, has another 147 pending, and is a vocal advocate for re-arming America’s military forces and citizens, following decades of incessant assaults that drove most U.S. firearms and ammunition manufacturers out of business.

Today, Karl Lippard is committed to reversing that trend and ensuring the United States can defend itself against all enemies, all the time. His vision covers the spectrum from semiautomatic .45-caliber pistols and unique rifles (his patented designs) to a new class of naval Gunship Destroyers capable of once again supporting troops ashore. He currently holds a $65-billion letter-of-commitment that underwrites a proposal to build and deliver 50 of these cutting-edge gunships for the U.S. Navy.

But that’s another story in the Karl Lippard saga. After seven decades, this seasoned, scarred American warrior is still fighting and winning. Stay tuned.

* Based on the few official records available, and the memories of those involved in the Ca De River bridge engagement of 28-29 July 1965. All photos and graphics courtesy of Karl Lippard.

Written by Bill Scott for the William B. Scott Blog ~ June 7, 2018

FAIR USE NOTICE:

FAIR USE NOTICE:

Many thanks for re-posting Karl’s amazing story. It’s now one of 18 true accounts featured in a new book, COMBAT CONTRAILS: VIETNAM, available from Amazon and the book’s publisher, NorthSlopePublications.com.