There’s an old story worth retelling about a band of wild hogs which lived along a river in a secluded area of Georgia. These hogs were a stubborn, ornery, and independent bunch. They had survived floods, fires, freezes, droughts, hunters, dogs, and everything else. No one thought they could ever be captured.

There’s an old story worth retelling about a band of wild hogs which lived along a river in a secluded area of Georgia. These hogs were a stubborn, ornery, and independent bunch. They had survived floods, fires, freezes, droughts, hunters, dogs, and everything else. No one thought they could ever be captured.

One day a stranger came into town not far from where the hogs lived and went into the general store. He asked the storekeeper, “Where can I find the hogs? I want to capture them.” The storekeeper laughed at such a claim but pointed in the general direction. The stranger left with his one-horse wagon, an axe, and a few sacks of corn.

Two months later he returned, went back to the store and asked for help to bring the hogs out. He said he had them all penned up in the woods. People were amazed and came from miles around to hear him tell the story of how he did it.

“The first thing I did,” the stranger said, “was to clear a small area of the woods with my axe. Then I put some corn in the center of the clearing. At first, none of the hogs would take the corn. Then after a few days, some of the young ones would come out, snatch some corn, and then scamper back into the underbrush. Then the older ones began taking the corn, probably figuring that if they didn’t get it, some of the other ones would. Soon they were all eating the corn. They stopped grubbing for acorns, and roots on their own. About that time, I started building a fence around the clearing, a little higher each day. At the right moment, I built a trap door and sprung it. Naturally, they squealed and hollered when they knew I had them, but I can pen any animal on the face of the earth if I can first get him to depend on me for a free handout!“

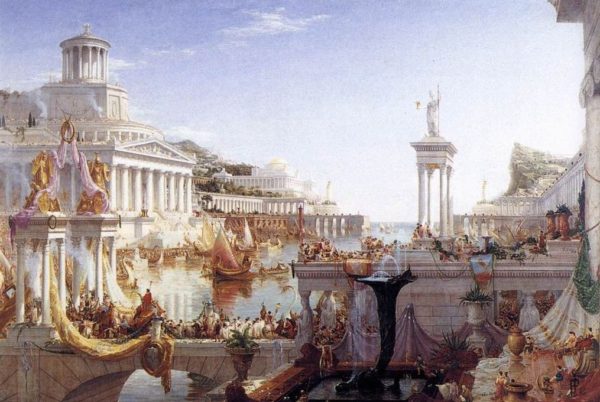

Please keep that story in mind as I talk about Rome and draw some important parallels between Roman history and America’s situation today.

Roman civilization began many centuries ago. In those early days, Roman society was basically agricultural, made up of small farmers and shepherds. By the second century B.C., large-scale businesses made their appearance. Italy became urbanized. Immigration accelerated as people from many lands were attracted by the vibrant growth and great opportunities the Roman economy offered. The growing prosperity was made possible by a general climate of free enterprise, limited government, and respect for private property. Merchants and businessmen were admired and emulated. Commerce and trade flourished and large investments were commonplace.

Historians still talk today about the remarkable achievements Rome made in sanitation, public parks, banking, architecture, education, and administration. The city even had mass production of some consumer items and a stock market. With low taxes and tariffs, free trade and private property, Rome became the center of the world’s wealth. All this disappeared, however, by the fifth century A.D., and when it was gone, the world was plunged into darkness and despair, slavery and poverty. There are lessons to be learned from this course of Roman history.

Why did Rome decline and fall? In my belief, Rome fell because of a fundamental change in ideas on the part of the Roman people—ideas which relate primarily to personal responsibility and the source of personal income. In the early days of greatness, Romans regarded themselves as their chief source of income. By that I mean each individual looked to himself—what he could acquire voluntarily in the marketplace—as the source of his livelihood. Rome’s decline began when the people discovered another source of income: the political process—the State.

When Romans abandoned self-responsibility and self-reliance, and began to vote themselves benefits, to use government to rob Peter and pay Paul, to put their hands into other people’s pockets, to envy and covet the productive and their wealth, their fate was sealed. As Dr. Howard E. Kershner puts it, “When a self-governing people confer upon their government the power to take from some and give to others, the process will not stop until the last bone of the last taxpayer is picked bare.” The legalized plunder of the Roman Welfare State was undoubtedly sanctioned by people who wished to do good. But as Henry David Thoreau wrote, “If I knew for certain that a man was coming to my house to do me good, I would run for my life.” Another person coined the phrase, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” Nothing but evil can come from a society bent upon coercion, the confiscation of property, and the degradation of the productive.

In 49 B.C., Julius Caesar trimmed the sails of the Welfare State by cutting the welfare rolls from 320,000 to 200,000. But forty-five years later, the rolls were back up to well over 300,000. A real landmark in the course of events came in the year 274. Emperor Aurelian, wishing to provide cradle-to-grave care for the citizenry, declared the right to relief to be hereditary. Those whose parents received government benefits were entitled as a matter of right to benefits as well. And, Aurelian gave welfare recipients government-baked bread (instead of the old practice of giving them wheat and letting them bake their own bread) and added free salt, pork, and olive oil. Not surprisingly, the ranks of the unproductive grew fatter, and the ranks of the productive grew thinner.

I am sure that at this late date, there were many Romans who opposed the Welfare State and held fast to the old virtues of work, thrift, and self-reliance. But I am equally sure that some of these sturdy people gave in and began to drink at the public trough in the belief that if they didn’t get it, somebody else would.

Someone once remarked that the Welfare State is so named because, in it, the politicians get well and you pay the fare! There is much truth in that statement. In Rome, the emperors were buying support with the people’s own money. After all, government can give only what it first takes. The emperors, in dishing out all these goodies, were in a position to manipulate public opinion. Alexander Hamilton observed, “Control of a man’s subsistence is control of a man’s will.” Few people will bite the hand that feeds them!

Civil wars and conflict of all sorts increased as faction fought against faction to get control of the huge State apparatus and all its public loot. Mass corruption, a huge bureaucracy, high taxes and burdensome regulations were the order of the day. Business enterprise was called upon to support the growing body of public parasites.

In time, the State became the prime source of income for most people. The high taxes needed to finance the State drove business into bankruptcy and then nationalization. Whole sectors of the economy came under government control in this manner. Priests and intellectuals extolled the virtues of the almighty emperor, the Provider of all things. The interests of the individual were considered a distant second to the interests of the emperor and his legions.

Rome also suffered from the bane of all welfare states, inflation. The massive demands on the government to spend for this and that created pressures for the creation of new money. The Roman coin, the denarius, was cheapened and debased by one emperor after another to pay for the expensive programs. Once 94% silver, the denarius, by 268 A.D., was little more than a piece of junk containing only .02% silver. Flooding the economy with all this new and cheapened money had predictable results: prices skyrocketed, savings were eroded, and the people became angry and frustrated. Businessmen were often blamed for the rising prices even as government continued its spendthrift ways.

In the year 301, Emperor Diocletian responded with his famous “Edict of 301.” This law established a system of comprehensive wage and price controls, to be enforced by a penalty of death. The chaos that ensued inspired the historian Lactantius to write in 314 A.D.: “After the many oppressions which he put in practice had brought a general dearth upon the empire, he then set himself to regulate the prices of all vendible things. There was much bloodshed upon very slight and trifling accounts; and the people brought provisions no more to markets, since they could not get a reasonable price for them; and this increased the dearth so much that at last after many had died by it, the law itself was laid aside.”

All this robbery and tyranny by the State was a reflection of the breakdown of moral law in Roman society. The people had lost all respect for private property. I am reminded of the New York City blackout of 1977, when all it took was for the lights to go out for hundreds to go on a shopping spree.

The Christians were the last to resist the tyranny of the Roman Welfare State. Until 313 A.D., they had been persecuted because of their unwillingness to worship the emperor. But in that year they struck a deal with Emperor Constantine, who granted them toleration in exchange for their acquiescence to his authority. In the year 380, a sadly-perverted Christianity became the official state religion under Emperor Theodosius. Rome’s decline was like a falling rock from this point on.

In 410, Alaric the Goth and his primitive Germanic tribesmen assaulted the city and sacked its treasures. The once-proud Roman army, which had always repelled the barbarians before, now wilted in the face of opposition. Why risk life and limb to defend a corrupt and decaying society?

The end came, rather anti-climactically, in 476, when the German chieftain, Odovacer, pushed aside the Roman emperor and made himself the new authority. Some say that Rome fell because of the attack by these tribes. But such a claim overlooks what the Romans had done to themselves. When the Vandals, Goths, Huns and others reached Rome, many citizens actually welcomed them in the belief that anything was better than their own tax collectors and regulators. I think it is accurate to say that Rome committed suicide. First she lost her freedom, then she lost her life.

History does seem to have an uncanny knack of repeating itself. If there’s one thing we can learn from history, it is that people never seem to learn from history! America is making some of the same mistakes today that Rome made centuries ago.

In many ways, the American Welfare State parallels the Roman Welfare State. We have our legions of beneficiaries, our confiscatory taxation, our burdensome regulation, and of course, our inflation. Let me talk specifically about inflation, which I regard as the single most dangerous feature of life today.

Everyone says he is against inflation. Every president has his war on it. Yet it rages on. Why? For two reasons. One, most people, especially those in high places, don’t really know what it is. And two, an inflationary mentality pervades our society.

Defining inflation properly is critical to our understanding of it. The typical American thinks inflation is “rising prices.” But the classical, dictionary definition of the term is “an increase in the quantity of money.” In this discussion, changing the definition changes the responsibility! If you believe that “inflation” is “rising prices,” and then ask, “Who raises prices?” you’ll probably say that “Business raises prices, so business must be the culprit.” But if you define “inflation” as “an increase in the quantity of money,” and then ask, “Who increases the money supply?” you are left with only one answer: GOVERNMENT! Until we understand who does it, how can we ever stop it?

Why does government inflate the money supply? By far the main reason is that people are demanding more and more from government and don’t want to pay for it. This causes government to run deficits, which are largely made up by the expansion of money. It follows, then, that inflation will not stop until the American people restore the old values of self-responsibility and respect for private property.

Let me show you how our Welfare State mentality has ballooned the federal budget. In 1928, the federal government spent a grand total of $2.6 billion. In the current fiscal year, it will spend over $530 billion. The accumulated red ink for the past five years is over $200 billion.

I’ve cited on other occasions a welfare recipient’s letter to her local welfare office: “This is my sixth kid. What are you going to do about it?” Implicit in that letter was the notion that the individual’s problems are not really his at all. They’re society’s. And if society doesn’t solve them, and solve them fast, there’s going to be trouble. I submit that our economy can withstand a few thousand, or even a million people who think that way, but it cannot bear up under tens of millions practicing that destructive notion. Today, what business, what school, what union, what group of individuals is not either receiving some special favor, handout or subsidy from government or at least seeking one? There’s no longer any reason to wonder why we have inflation.

According to Dr. Hans Sennholz of Grove City College, the development of the American Welfare State has come in two phases. In the first phase, roughly from the turn of the century to 1960, we relied mainly on ever-increasing tax rates to finance the expensive government programs. The top tax rate went from 24% to 65% under Herbert Hoover and to 92% under Franklin D. Roosevelt. The decade of the 1950s was one of stagnation under these oppressive, capital-confiscating rates. So we had to find a supplementary method to raise the needed revenue. The second phase of the Welfare State began in the 1960s, with a deliberate policy of massive, annual deficits in the federal budget and an addiction to the printing press. The demands to spend for this and spend for that, which I have mentioned above, have merely provided the fuel for these massive deficits.

America’s dilemma is certainly of crisis proportions. We face collapse and dictatorship if inflation is not stopped and the growth of government is not checked. But Rome’s fate need not be ours. Our problems stem from destructive ideas, and if those ideas are changed, we can reverse our course. A nation that can put a man on the moon can resolve to mold a better future. Let’s reject the destructive notions of the Welfare State, and embrace the uplifting ideas of freedom, self-reliance, and respect for life and property.

November 2, 1979

Written by Lawrence W. Reed for the Foundation for Economic Education